Hey, I was there to help, right? Right there in the kitchenette loaned us by the Roosevelt Hotel in Anchorage. My wife in those days, Pam, ran the headquarters for the Iditarod Dogsled Race, and it was the second year of the race, 1974, and there I sat, a genuine Alaskan long-distance dog musher who had participated in the first race the year before.

So when a nicely dressed elderly gentleman with a thick Boston accent stopped by for coffee and questions about the race … hey, I’m there for you.

He said his name was Norman Vaughan and he had some questions, and we talked for more than an hour. Oh, I explained to this obvious city guy all about how the dogs were hooked up, and how far we could go each day, depending on weather. He was a good student, too. When he rose to go, he said, “Slim, I think we’ll be seeing a lot of each other and become good friends.”

Okay …

I’d never thought of dog mushing as something an elderly gentleman in a suit and tie from Boston would be interested in, but I’ve been fooled before. As a newspaperman, I’ve interviewed all kinds of fascinating folks over the years.

But there was something about Norman that I genuinely admired, even if I couldn’t have said exactly what it was.

Pam and I discussed how this race had captured the attention of the world after just its inaugural run. For the record, it has begun (for 50 years now) on the first Saturday in March in Anchorage, then crosses Alaska to end up on Front Street in Nome in front of the Board of Trade Saloon, where Wyatt Earp was once the bartender, back when Nome was a boom town. This gives a guy a long, cold camping trip before he gets to Front Street. Many aren’t able to complete the race for various reasons, and I was one of those. Four days in, I crushed an ankle. I crawled in the sled and the team took me 20 miles to the next checkpoint, where I was ignominiously airlifted to a hospital in Anchorage by Army helicopter.

The race was the long-time dream of Joe Redington, Sr.. and it took him years of cajoling and arm twisting to get it on board. He laughed when he heard race participants call if “The Idiot Road,” but it’s good to occasionally have truth in advertising.

People came from all over the world to see the race, but in truth it isn’t a spectator sport. You can watch the teams leave Anchorage … they let a team go every two minutes to avoid massive dog fights … and you can watch them cross under the log arch on Front Street in Nome if you time it right.

But in between it’s camping and meeting nice people at the trappers’ cabins and Native villages you pass through.

So I guess it’s only natural that a Boston gentleman would be interested in seeing how something like this could happen. And that’s what Pam and I were discussing for the next half hour after Norman left.

Pam mentioned how nice it was of me to fill our visitor in on the wonderful world of dog driving. Hey, our cabin was 12 miles from the nearest road, and we had to drive the dogs to get to the car, right? Experienced dog mushers, both of us.

So about a half hour after Norman left, we were discussing him and sipping coffee when the news guy on the radio said, “The special guest speaker at the musher’s banquet tonight will be Colonel Norman Vaughan, who drove a dog team to the South Pole in support of the Byrd Expedition in 1930.”

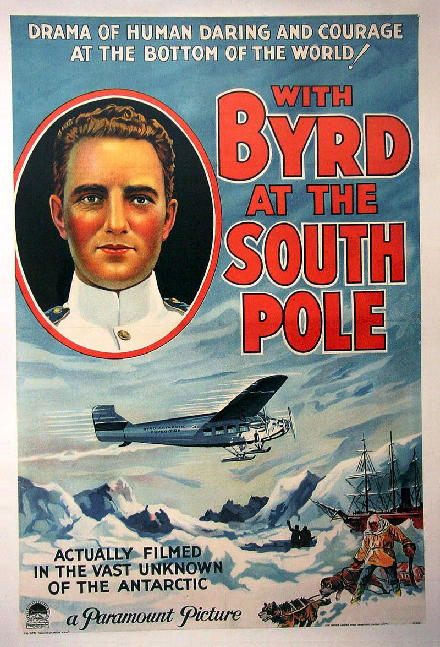

Poster for the documentary "With Byrd at the South Pole" including Norman Vaughn, 1930

Poster for the documentary "With Byrd at the South Pole" including Norman Vaughn, 1930

I didn’t have to say anything because Pam was laughing so hard she couldn’t have heard me anyway. Much to my regret, the floor in the Roosevelt Hotel didn’t open up and swallow embarrassed dog mushers. I’ve had to live with the memory all this time.

Norman Vaughan drove his dog team to the South Pole as a possible rescuer in case Richard Byrd’s plane was forced down. During World War II, Norman was in charge of dog team rescue in Greenland, where they could rescue any air crews forced down on the ice cap. More than 100 fliers were rescued by his dog teams.

Byrd named a peak in Antarctica after Norman and Norman went down there and climbed it with some friends just before his 89th birthday. He and I were friends for the rest of his life, and when Norman Vaughan finally was able to finish the Iditarod Race in Nome, one of my dogs was his leader.

But after giving this polar explorer the benefit of my vast experience in that hotel room for more than an hour, about all I could do was grin and shrug and say, “Well, at least now he knows how to do it the right way.”

Brought to you by Dogsled, A True Tale of the North. From the University of New Mexico Press.