Discover the story of the Pacific NW at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

March 4, 2024 at 6:00 a.m.

Each site offers a glimpse into the park’s rich cultural past, from a frontier fur trading post to a powerful military legacy and the thrill of flight. You’ll hear stories of settlement, conflict and community, as you wander through buildings full of artifacts and speak with knowledgeable docents.The British Hudson’s Bay Company established the extensive fur trading network throughout the PNW and built Fort Vancouver to serve as its administrative center and main supply depot. Today, the reconstructed 1840s era Fort and Village brings to life the lives of Native Americans, settler and fur trappers who resided in the area.

The Village was home to the workers and their families who supported the operations of the fur trading post and its farms, dairies and mills. In its heyday, the Village housed over 500 people from a variety of backgrounds, including Native Hawaiians, French-Canadians, English, Scots and members of more than thirty different Indian tribes. Two reconstructed houses gives you a sense of the vibrant and complex life of the community.As you walk the path to the fort, you’ll pass a large garden. Historically, the garden at the fort covered from five to eight acres and abounded with flowers and produce. Though I visited during late fall when it was dormant, I was told that in the spring and summer, the garden is a place of horticultural beauty, bursting with plants that still provide produce and blooms bursting in color. Many represent varieties from the era.

Inside the fort, the most prominent building is the Chief Factor’s House or the “Big House.” The two top officers at the post and their families resided inside and entertained guests. And the fort’s highest ranking men gathered here to discuss news and strategies and make policies and deals.

The house was definitely designed to impress, with its height, staircase and veranda, garden and the pair of cannons placed front and center.You’ll also find a number of other interesting buildings in the fort; several of which may have docents in residence, dressed in period costume, and performing work that would have been done in the 1800s.

The blacksmith shop, for example, is where the “smith” would have combined the functions of a welding shop, service station and hardware store. He was a valuable man in the fort, as every community needed a good blacksmith. Often there was at least four on the job at any one time. And they labored long and hard to make almost every article for home or farm that couldn’t be formed of wood.Blacksmiths required technical skill and years of experience. They had to first build a fire in the forge, using coal or charcoal. To do this, they pumped a bellows attached to the forge to force in oxygen and stoke the flames into a raging fire. Then they placed bars of iron or steel shipped from Britain in the fire. When the iron turned red-hot, they could bend and beat the bars into shape using a hammer and anvil.

During my tour, two men were busy manufacturing historically accurate tools and hardware from iron. We were told that a smith’s tasks were arduous and that their talents were always in demand. The downside being that they had to work in sweltering, dirty conditions for hours.

In the fort’s reconstructed kitchen, it was easy to imagine that this was once a bustling spot with steaming kettles, meat roasting over the fire, women chopping veggies and people scurrying all about the place. We watched as several docents hung beans to dry, prepared salmon in parchment, made bread and other items using recipes from the 1800s. Preservative techniques in those days included salting, smoking, drying and pickling. And you’d best start early when baking anything, as the brick oven took two hours to heat.It smelled good in there, though we learned that in addition to fragrant cooking aromas, you would also have odors of pipe tobacco and sweaty bodies in those days!

The kitchen was a hive of other activities, too, from dishwashing and candle making to shoe polishing and heating the shaving water for the residents of the Big House and Bachelors Hall. It was a staggering amount of work for those who toiled here.

Over at the Indian Trade Shop, a gentleman informed us that this storehouse held furs and other goods, including beads and buttons, tools, tobacco, fire starter kits, animal traps, guns and ammo, fabric and Hudson’s Bay Company blankets that were used in exchange for the furs. Native Americans were often employed at the store “with strategic attention to how these individuals – and their tribal affiliations – would be perceived by visiting Indian traders.”

Beaver pelts were in big demand, as clothing made from the pelts were very much in fashion. An individual would receive up to four “markers” per pelt depending on its quality. The markers were then used to purchase items at the store.

Construction and repair needs at the fort and outlying mills and farms mandated a Carpenter Shop, which was typically staffed by three to five carpenters, apprentices and assistants. They were tasked with building framing for the buildings, doing finish work, joining and other duties. The men kept occupied, not only with the above jobs, but with the building and repairing of wheels, carts and wagons, along with crafting wooden parts for farm equipment.

On our visit to the Carpenter Shop, two men showed us how a mortise (slot or hole) and tenon (pin) was used instead of nails to make furniture and houses. The mortise and tenon is one of the most common joints and is an old woodworking technique dating back thousands of years that is still used today. Put simply, it allows two pieces of wood to be connected. But it requires great precision in measuring and cutting. I liked the look of no nails in the wood, and hearing that it’s strong and durable was an undeniable plus.

In 1849, the U.S. Army arrived and constructed the Vancouver Barracks adjacent to Fort Vancouver. This was the first U.S. Army post in the PNW and remains one of the country’s most historic military posts. When the Hudson’s Bay Company abandoned the fort eleven years later, the Army took it over. A fire destroyed the fort in 1866, but the facility continued to operate in different forms until the National Park Service stepped into the picture.

Though many of the buildings at the Vancouver Barracks are closed to the public, wayside exhibits throughout the area offer info about the history of this military post. You can also stroll along Officers Row, a tree-lined promenade featuring nearly two dozen preserved Victorian homes on the National Historic Register. These homes once housed U.S. Army officers station at the barracks. Only three are open to the public: the Grant House, George C. Marshall and O.O. Howard House.

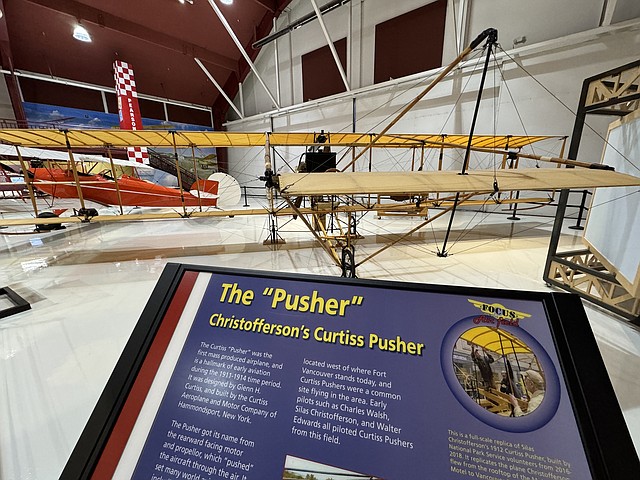

Nearby is the Pearson Air Museum and Pearson Field. The latter is one of the oldest operating airfields in the U.S. Known as the birthplace of West Coast aviation, it’s named after Lt. Alexander Pearson, a legend in the industry, who won the first cross-country air race and made the first aerial survey of the Grand Canyon. Today, the field operates as a busy municipal airport and offers a flight school, aircraft rentals, maintenance and restoration services.

The museum is worth a looksee, especially if aviation is your thing. It celebrates the long aviation history of Pearson Field through aircraft and exhibits.

Though I didn’t get a chance to visit the McLoughlin House in Oregon City this time around, if the opportunity arises when I return to the area, I’ll certainly check it out. The restored home tells of the life and accomplishments of John McLoughlin, known by many as the “Father of Oregon.”

McLoughlin was a trained, British physician who once presided over British fur trade interests for the Hudson’s Bay Company. He was the longest serving Chief Factor at Fort Vancouver. Forced into retirement, he and his family settled into this home in 1846. McLoughlin became an American citizen a few years later and served as the mayor of Oregon City. He promoted the economic prosperity of the Oregon Territory and was known for loaning money to emigrants to assist them in establishing businesses. He also donated land for schools and churches. The house is on the Oregon National Historic Trail.

Debbie Stone is an established travel writer and columnist, who crosses the globe in search of unique destinations and experiences to share with her readers and listeners. She’s an avid explorer who welcomes new opportunities to increase awareness and enthusiasm for places, culture, food, history, nature, outdoor adventure, wellness and more. Her travels have taken her to nearly 100 countries spanning all seven continents, and her stories appear in numerous print and digital publications.