Dear Mom and Dad,

It's been a long journey since you departed. We miss you so very much.

Mom, it's hard to believe that more than three years have passed since you left this earth. Then Dad, you joined her soon after.

We hope you love your new accommodations, and I don't just mean heaven. Completing the arrangements for your final resting place -- where you reside together -- was a journey all into itself. It's been years since we said our last goodbyes, and yet we laid you to rest only a short time ago. That is the reason I'm writing this letter today, so long after you passed away. But more on that later.

Mom, even with advanced kidney disease, even while confined to home because of the pandemic, even while recovering from hip surgery, you remained engaged with life, enjoying simple pleasures that came your way: custard and other special treats, talking to your kids and grandkids, connecting daily with your lifelong best friend (who lived right next door), watching your favorite shows, listening to hymns... Both sad and funny to say, you also enjoyed the big, burly paramedics, dressed in full regalia, who arrived to gently lift you up each time you fell. But until that hip fracture, you refused to use a walker. You would simply wave your hand and fiercely shake your head no. "I don't need that! I'm careful!" Even your beloved doctor could not convince you of the wisdom of a mobility aid. You were stubborn.

You accepted with pride your doctor's exclamations that you were a true miracle, living as you did with kidney disease, year after year. You declared early on that you would not have dialysis, although we sincerely hoped to change your mind. But, as you always said -- like your favorite song -- you were ready to fly away. You flew away not long before your 95th birthday.

Dad, it came as no surprise that after 80 years of knowing Mom, life no longer made sense without her by your side. You wanted to live to 100, and you made a valiant effort. Nearly 98 is nothing to sneeze at. (When I think of you and sneezing, I remember that Mom said you always sneezed seven times in a row. She counted them every time.) I do believe you would have made 100 were it not for the pandemic. Neither of you contracted the disease, but I remain convinced that it cut your lives short because of the complete change to your active routines.

I was always amazed at how much energy and zest for life the two of you kept as you grew older. Age didn't slow you down. Family get-togethers, great grandkids' sporting events, visits with relatives, driving trips, going to church. You never missed a birthday and always tucked a one-hundred-dollar bill into the card. Even without special events, you did the rounds and went out nearly daily. Dad, you were able to safely drive until very late in life. More than once, when I joined you for out-of-town family events, relatives would comment on how nice it was of me to chauffeur you and Mom. But actually, you were the driver. You finally gave up the keys very late in life, with just a little prodding. That was a hard one for you. In the end, a few slow trips to the Dollar Store just three blocks away with you behind the wheel and one of us vigilant by your side helped ease the transition.

But even after your children began driving the two of you on your errands and to doctor's appointments, you mostly kept up that active pace. Frequent trips to Fred Meyer and the Dollar Store became social events and adventures all on their own, with cheerful greetings from your favorite checkers -- you knew their names and they yours; giving cash to the same guy looking for handouts on the street. One time he said, "Thank you, but gosh, you don't have to give me money every time!" You did anyway, once driving around to find him when he wasn't at his usual station. He received an extra large donation that time.

I think of your Fred Meyer routine, Dad, taking the large shopping cart to circle the aisles, going up and down and around, not so much for the shopping but for the exercise it provided. Mom, you preferred the small cart, finding the one or two items from your list, then doing your people-watching from the car. I know it doesn't sound very exciting to the wider world, but Fred Meyer was one of your tricks for getting out, seeing people, and remaining physically active. Dad, you could walk confidently with that big cart and not look like you had the need for a walker. It fit you just fine. Later on, after the pandemic, the two of you found a bit of solace in scenic drives or quick trips to the drive-through (a Blizzard or McFlurry for Dad, and a chocolate or caramel Sundae for Mom). Because we, your children, were considered part of your care team, we visited even during the pandemic. We were grateful that you were still at home, and not in a facility that would keep us apart.

When the vagaries of old age truly grabbed hold of you -- first you, Mom, after you broke your hip and kidney disease finally caught up with you... and then Dad, you declined rapidly when you lost Mom -- we soon realized we could not handle your care on our own. We quickly learned the ins and outs of hiring home health care. Even with 'round the clock care and one of us visiting every day to socialize, do the errands and paperwork, get your dinner... even with the caregivers there, the rigors of caring for you was overwhelming at times. I often found myself wondering how people manage, those without the financial means to hire help and especially those without family to participate in their care.

I remain amazed: each of you from such humble backgrounds, working so hard to support your large family on a small income that frequently ran out before the next paycheck, yet somehow managing to amass a minor fortune -- enough to live in your apartment with its million dollar view, enough to pay for 'round-the-clock caregivers (an incredibly expensive proposition), and still enough to leave your children a tidy inheritance. Throughout our entire lives, until the very end and beyond, you have always been there for us.

Dad, it was a blessing when you become confused enough to forget that Mom had left us. You were convinced she was living in the nursing home upstairs (what in reality was your small three-unit condo building). When we tucked you into bed at the end of the day, you would ask, "Did you leave enough room for your mother? She comes to visit me at night, you know." Yes, Dad. We always left room for Mom.

My parents' last outing together, at one of their favorite places in the world, the church camp on Samish Island. A memorial bench with their names is located at the camp, overlooking the beautiful views. Five weeks and one day after this photo was taken, Mom had flown away into the great beyond.

My parents' last outing together, at one of their favorite places in the world, the church camp on Samish Island. A memorial bench with their names is located at the camp, overlooking the beautiful views. Five weeks and one day after this photo was taken, Mom had flown away into the great beyond.I think you would both be happy with your memorial services.

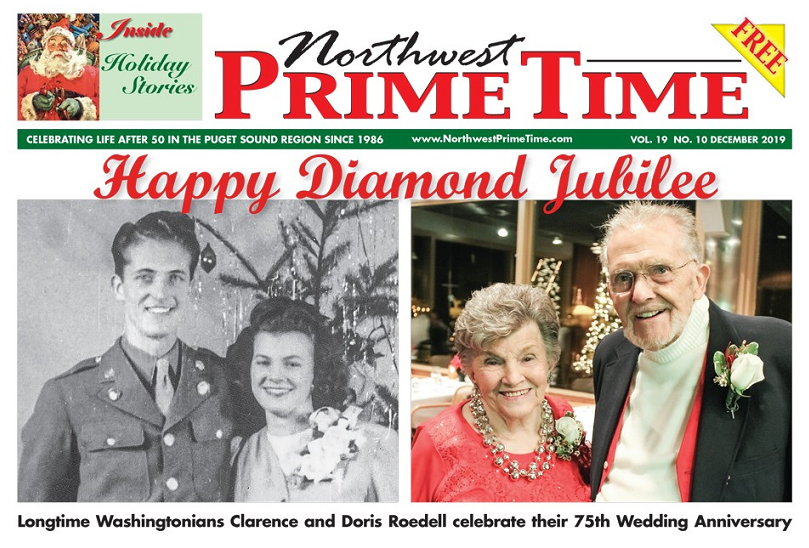

Mom, the pandemic caused us to be creative. A very large picnic shelter did the trick. Your program began: Doris Roedell had a big heart. She was gentle, generous and kind. She welcomed and accepted everyone. Visitors were rewarded with a warm, happy smile. She was genuinely glad to see you -- even if she had never met you before. She would always help you out, no questions asked. If you were sick, she was there to take care of you or even your ailing pets. Doris' biggest wish in life was that she wanted everyone to be happy. Yes, Doris was gentle and kind, but she also loved to laugh and had a secret, mischievous streak. She enjoyed many adventures during her long life.

Dad, by the time you were gone, the pandemic rules had relaxed, and we were able to hold the services at church, which was a second home to you and Mom. Part of your program read: To make ends meet, June [your nickname, of course] once held three jobs, but eventually found a great career at Boeing researching lasers.... June was handy and it seemed he could do just about everything. Besides that, he would do anything for his family; you could count on him. He was a man of great character. Plus, he WAS a character. He had a unique sense of humor and often reveled in being kooky. He and Doris made an unbeatable team. She wanted everyone to be happy; he wanted everyone to have fun. June was a true original; he was one of a kind.

Individually, you were each one of a kind. As parents, you were sublime.

Your wish was to be cremated and laid to rest together, but you left the final arrangements to us. Until we made those arrangements, your ashes remained in a place of honor at your daughter Susan's home.

When the shock began to wear off -- that life was to be lived without you -- we started to think about where you would spend eternity together. It didn't take a great leap of the imagination to consider the empty grave that sat next to our grandparents and beside our aunt. It was the perfect place. A bit of my sister's ashes also snuggles up alongside my grandmother's grave there. Our grandfather purchased those four gravesites in the 1960s. My aunt was laid to rest in 1965. Loulie and Gramps, as we called them, were buried in 1988 and 1985. The other grave, jointly owned by Gramps' heirs, lay empty all those years.

Leaving flowers at the cemetery has been a long tradition, and when you passed away, we left flowers on that empty grave in your honor, hoping someday to receive permission to bury you there. Each birthday, each death day, every Father's and Mother's Day, your anniversary... Leaving flowers on that empty gravesite while thinking of you has brought me comfort.

It took years to determine that all the heirs were happy to give you that special place. Three years to the day Mom died, your urns were placed in a small vault together and lowered into the ground while the hauntingly beautiful Taps floated around your loved ones. Etched into the vault cap are your names and a lovely scene of two birds flying off together, with the words, Going Home.

On December 23, 2024, what would have been your 80th wedding anniversary, I will visit the cemetery. As always, I will leave flowers for my grandparents, for my aunt, for my sister. But this time, as I leave flowers especially for you -- my dearest departed parents -- the flowers will not be laid upon an empty grave. You will be resting below the vivid petals, cradled together, at peace and forever in our hearts.

- - - - -

Dear Readers: The following article about my parents was featured on our cover in December 2019. I hope you will enjoy the folksy story of the early life and courtship of Clarence and Doris Roedell, who celebrated their 75th wedding anniversary that month.

It was the eve of Christmas Eve, 1944, long, dark months before the end of WWII.

A young G.I. and his even younger bride walked the aisle of the chapel at Central Lutheran Church on Seattle’s Capitol Hill. Some believed the impromptu wedding to be a triumph, considering the obstacles along the way.

But first, let’s roll the story back a few years...

“Come on out, it’s the Garden of Eden”

So goes Roedell family lore when Clarence’s great-grandmother implored her Dust Bowl stricken relatives to follow after moving during the Great Depression from Iowa to the Nooksack area, a farming hamlet in the far northern reaches of Washington State.

Follow they did. Three Roedell brothers had married three Parker sisters—uniting two families with 26 siblings between them. Those families proceeded to have a ton of kids of their own, including Clarence. The Parker- Roedells, along with the rest of the Parker clan, loaded up their cars and trucks and caravanned across the country.

The sheer numbers of the Parkers and Roedells made quite an impact on sleepy Nooksack Valley. Clarence’s extended family in the area included dozens of cousins, 17 of which were “double-cousins,” related on both sides since their fathers were Roedells and mothers Parkers, just like Clarence. (Sadly, Clarence’s double-cousins became motherless when two of his Parker aunts died before the epic move to Washington.)

Clarence was 12 when he arrived in Nooksack on the 4th of July 1937. He, along with his parents, two sisters, baby brother and their dog Terry made the trip in a fifty-dollar Essex and $25 in cash. They camped along the way (once experiencing the luxury of a motel while dealing with the broken-down Essex in Wyoming), eventually arriving in the verdant valley they came to call home.

The transition wasn’t easy for any of the Roedells or Parkers, but Clarence’s grandmother, Addie, had come to Nooksack earlier, following her own mother. Her humble home at the edge of town became known among locals as “Ma Parker’s Hotel” (Judge Harden’s old place); Addie’s myriad of relatives had a landing place at “the hotel” when they arrived. Bunks were built into the walls of the dining room to accommodate all those kids.

Like most during the Depression, Clarence’s father struggled to find work, taking odd jobs here and there. Clarence pitched in, arising each morning at 6am in the unfinished attic that was his bedroom to their Swedish landlord, who pounded on the ceiling below with a broomstick, calling: “Yunior, time to get up and milk the cows.” Before they found refuge at that dairy farm, their house had burned to the ground, along with all they owned. The kids were temporarily shipped out to stay with relatives. Luckily, there was no shortage right in the neighborhood.

Despite the hardships, Clarence thrived in Nooksack, sporting around in his dad’s Model A Ford, playing center on the high school basketball team (Gale Bishop, who turned professional after attending WSU, played there too), and hanging out with his friends and double cousins.

Flag Twirlers & Boeing’s Red Barn

Meanwhile, Doris Scott spent her formative years from 5th to 10th grade at the other end of the state in Colfax, a bustling wheat town in the scenic Palouse, a hop-skip-and-a-jump from Washington State University. She camped with the Campfire Girls, watched movies, went to dances and marched as a flag twirler at parades and school games.

Doris had two sisters and a brother but spent as much time as possible with her two best friends. The three were known to dress alike and it was always a thrill when one of the mothers would drive the trio into Spokane to pick out dresses, especially for an important event like the Junior Prom.

Before the family moved to Colfax, they shuffled around quite a bit as her parents looked for work. Doris was born on Seattle’s Beacon Hill but moved to her father’s family farm in Valley (north of Spokane) when she was about three. They later relocated to Spokane among other places, but Doris especially remembers the farm where she learned how to milk the cow to feed the kitty. She recalls the gentle cow with fondness: “Old Bess wouldn’t hurt anyone.”

Life in Colfax was fun for Doris, despite the hardship of having a fulltime working mother and a father disabled from mustard gas during WWI. It was a shock when she learned that her pleasant life was about to be uprooted because they were moving to Seattle. Her mother would soon be working as a “Rosie the Riveter” at Boeing’s historic birthplace, the Old Red Barn.

“Mother loved working there,” says Doris. “She had friends and was making good money. That was one of the happiest times of her life.”

Seattle’s wartime boom summoned thousands of workers from across the country. The Scotts and Roedells were no exception; both families arrived in the summer of ‘42 from opposite ends of the state. The Roedells moved into a brand-new apartment at Yesler Terrace overlooking downtown Seattle (their first home with indoor plumbing); the Scott’s moved to Capitol Hill with the smell of fresh-baked bread wafting in from nearby Langendorf Bakery.

When Doris Met Clarence

Before Doris met Clarence, she met his younger sister, Carol. Both were small-town kids thrown into big city life at Broadway High, confronted with cliques of girls who wore cashmere sweaters and saddle shoes. The two swiftly bonded and never looked back. High school life didn’t seem as important as skipping class each time a new Frank Sinatra picture hit town, or their jobs at Bartell’s (where they often met old Mr. Bartell, who was known to shake hands with his employees at Christmastime). School certainly didn’t seem as important as the romance that was about to bloom for the not quite 16-year-old Doris.

Doris spent a lot of time at Carol’s and sometimes Clarence saw her asleep on the couch when he came home after midnight from his job. “I thought she was cute,” says Clarence. “I thought he was pretty nice,” remembers Doris. He started calling her Dorie May; she called him June just like the rest of his family (short for Junior).

What was their courtship like? “We didn’t do much of anything at first,” says Doris. “We did a lot of necking,” reveals Clarence with a grin.

The relationship was growing strong until May of 1943 when Clarence went into the Army and was shipped out to New Orleans for basic training.

“I was lonesome,” says Doris of the separation. Frequent letters kept the long-distance relationship alive. They have kept those letters to this day.

Clarence was transferred to South Carolina where, at Christmastime, he received a one-week pass and decided to head home. Trouble was, home was a seven-day round-trip on the train. Once he arrived in Seattle, Clarence hoped he could finagle extra days. Otherwise, he would have to get straight back on the train. He considered the possibility of seeing Doris worth the risk.

Clarence fell asleep on the crowded train “settin’ on a suitcase because there wasn’t room anywhere. The vestibules were full of sailors.” That train was the Atlantic Coast Line that derailed in North Carolina on December 16, 1943. It is considered one of the worst train wrecks in U.S. history. Seventy-four people died in the crash. Clarence was among the 187 injured. He was to spend the next six months in the hospital.

Back home in Seattle, a reporter tracked down Clarence’s father and informed him that his son was killed in the wreck. Luckily, the truth came out before Doris heard the news.

That wreck and those long months of recovery probably saved Clarence’s life. His training as an amphibious pilot would have put him square in the Pacific theater of war, where statistics show that pilots of J-boats couldn’t necessarily expect to survive. After rehab he went back to duty, but his extensive injuries prevented him from shipping out.

As an aside, Clarence was Doris’ steady fella, although the couple didn’t have specific plans to marry. Nevertheless, she was already a part of the Roedell family. The Roedells were known for parlor games and a silly secret family initiation called “The Roedell Airline,” which Doris would soon experience first-hand. And despite not knowing when she herself might marry, Doris was no stranger to weddings or even honeymoons. For the record, although she may try to deny it, she accompanied her best friend Carol on her honeymoon. But that is another story.

By Christmastime 1944, Clarence was stationed in Florida. He received another pass and once again boarded a train for the three-and-a-half-day ride home. The young Doris, barely out of girlhood, began to fret about what to buy Clarence for a Christmas present. “I didn’t know what you were supposed to get for a serious boyfriend,” she says. A married friend suggested the same gift she got her husband: a lifetime subscription to Reader’s Digest. That $25 turned into a lifetime investment; after 75 years the magazine still arrives faithfully each month.

Married at Last

When Clarence arrived for his Christmas leave, the prospect of time together—however fleeting—prompted Clarence and Doris to tie the knot. Legally, the 20-year-old G.I. needed his mother’s permission to marry; the barely 18-year-old Doris didn’t. On behalf of her son, Clarence's mother bought Doris' ring second-hand. Doris loved that slim band, loved it so well it eventually wore out and broke. The couple replaced it with a one-of-a-kind custom made ring designed just for Doris.

A two-night honeymoon was spent at a relative’s apartment, then it was back to Florida for Clarence and back to her mother’s for the newly minted Mrs. Roedell.

But within a couple of months, Doris was able to follow her husband to Florida, riding a crowded train across the country. Wartime housing was scarce, and the couple lived for nearly a year on the porch of a rooming house, until young Doris found that she was pregnant. Clarence insisted she go back home, thinking she needed her family at a time like that.

But... “I was lonely without him,” says Doris. She wanted to return. “No,” declared Clarence. “And besides, I’m getting transferred to California.” Somehow that seemed like an invitation to Doris, and she made her way unannounced to her husband. After all, California is a lot closer than Florida.

Their small room at the Arlington California Hotel “had a window in it,” reports the couple, “but it was up in the ceiling. And the bathroom was down the hall.” Living conditions became a little uncomfortable for the very pregnant Doris, and she finally went back home.

“Then I was discharged from the Army in March of ‘46 and made it to Seattle a month before the baby was born,” says Clarence. The couple gratefully reunited and found a basement apartment on Capitol Hill to set up house.

Me and Queenie

Doris relays her brother-in-law’s joke: “Between me and our dog Queenie, one of us was always pregnant.” It was true. Their apartment became far too small after their third child was born. The couple was able to buy a house for $6,700 in a rural area south of Seattle. Three more kids quickly followed. The family was finally complete when the youngest brother joined the flock. His mother was Doris’ older sister. She and her husband both died, but not before entrusting their little one to the Roedells.

To make ends meet for his growing family, Clarence once held three jobs. His fulltime job was at King Street Station, but he also cleaned an office building at night and worked as a television and radio repairman. When his baby daughter cried at him—he’d become a stranger to her— Doris insisted he give up at least one of his jobs. Clarence eventually found a career at Boeing researching lasers.

The Roedells’ small house was always filled to the brim with their own kids, with neighborhood kids, with visiting relatives and plenty of pets (including the usual dogs and cats, but also bunnies, a parakeet, pet chickens, a goat and raccoon). In addition, the Roedells were destined to host another “Ma Parker’s Hotel.” Family and friends came to stay, sometimes for the weekend, sometimes for months or even a year. As Doris would say, “We can always find room, even if all we have to offer is the floor.”

Life Today

Clarence retired in 1989 after 29 years at Boeing plus a railroad pension from his time at King Street Station. With time and money no longer in short supply, the couple traveled to Europe, Africa, Hawaii and took countless road trips across the country, frequently accompanied by Carol and her husband. After 50 years in their modest home, the site of so many memorable family gatherings (often featuring those same parlor games and secret initiations, which continue to this day), they sold the place and eventually moved to nearby Des Moines. Now Clarence and Doris have a million-dollar view overlooking the marina, Puget Sound and Olympic mountains. They continue to live independently, sharing an oversized balcony with none other than Carol, who lives right next door.

Life is good, despite the physical ails that often accompany a long life, despite losing so many dear loved ones and friends. Clarence and Doris continue practicing the generosity and loving kindness they are known for, helping others without question.

With nine grandchildren and seven great-grands, the couple remains centerstage at frequent family get-togethers. Everyone is looking forward to an especially raucous hoorah on December 23, Doris’ and Clarence’s 75th anniversary.

- - - - -

NOTE TO READERS: This article was Northwest Prime Time's cover story back in December 2019, the month of my parents 75th anniversary. 2019 was a stellar year for honoring my parents. We had celebrated my father's 95th birthday earlier that same year by renting out the entire Tokeland Hotel for a truly remarkable birthday bash. We remain grateful that we were able to celebrate our parents' diamond jubilee and my father's 95th birthday before the pandemic struck. Those happy memories remain forever in my heart.