Gretchen Fraser: Hidden Gold

March 25, 2023 at 10:30 a.m.

She was the first U.S. woman to win an Olympic medal in skiing. Her face was once on a Wheaties box. So why don’t more people know about Gretchen Fraser?

Atop a mountain thousands of miles from home, Gretchen Kunigk Fraser ’41 eased into the starting gate, set into a crouch, and awaited the signal to start the biggest ski race of her life. The odds against Fraser were already tremendously long. The fact that she had even made it to this point—competing in the 1948 Olympic slalom event in St. Moritz, Switzerland, and clinging to a narrow one-tenth of a second lead as she began her second and final run in the competition—felt like something of a miracle. And now, as the brand-new timing system malfunctioned, Fraser learned she would have to wait even longer to begin her race.

The Olympics were not yet televised live in America, so halfway around the world, in Vancouver, Wash., Fraser’s husband, Don, a former Olympic skier himself who couldn’t break away from the family gas and home heating oil business to get to Europe with Gretchen, eagerly waited for news. In Sun Valley, Idaho, a burgeoning ski-resort town frequented by Hollywood celebrities where Don and Gretchen Fraser had come of age as competitive skiers, residents awaited word of the results. In Tacoma, where Fraser had grown up and attended University of Puget Sound, her parents eagerly anticipated a telegram or call from their daughter.

The American media who gathered in St. Moritz had arrived in Switzerland considering Fraser and her fellow members of the U.S. Ski Team an afterthought, the first post-war representatives of a sport that had only just begun to catch on in the country. For female skiers, it was even more difficult: They had no coach until the final weeks before the Olympics, and many people still debated whether skiing was “ladylike” enough for women to participate. As a full slate of alpine skiing events made its Olympic debut in the first winter games since 1936 (1940 and 1944 had been canceled due to World War II), nobody expected much of anything from the United States—and particularly from Fraser, who, at 28 years old, was the oldest member of the team.

In this undated photo, Gretchen Kunigk Fraser ’41 is interviewed by two members of the media, including radio station KVI, which at the time was based in Tacoma. It’s now licensed in Seattle. Photo courtesy of Puget Sound Archives & Special Collections.

In this undated photo, Gretchen Kunigk Fraser ’41 is interviewed by two members of the media, including radio station KVI, which at the time was based in Tacoma. It’s now licensed in Seattle. Photo courtesy of Puget Sound Archives & Special Collections.

Atop the mountain, the wait continued for Fraser. Two minutes. Five minutes. At 10 minutes, the starter allowed Fraser out of the gate to stretch her legs. She wore her hair in long braids, since between training and traveling she had no time to get it styled. Her goggles fogged up, so she pushed them up. Seventeen minutes after Fraser first stepped into the starting gate, the clock malfunction was fixed. Fraser, the first skier out of the gate that day, was entirely unruffled. She plunged down the hill into virgin snow, goggles clinging to her forehead as she maneuvered her way down the mountain at 60 miles per hour and weaved through the slalom gates in 57.5 seconds.

Somehow, Fraser had bested her first run. But now she had to wait even longer. Now she had to wait for 45 other competitors to ski the course and see if they could beat her.

No one did.

“A pretty western housewife, her pigtails flying,” read one newspaper article, “accomplished something no American had done before—win an Olympic medal for skiing.” Before the Games were over, she would go on to add a silver in alpine combined. Gretchen Kunigk Fraser ’41 showing off her two Olympic medals from St. Moritz: a gold in slalom and a silver in alpine combined. Photo courtesy Tacoma Public Library.

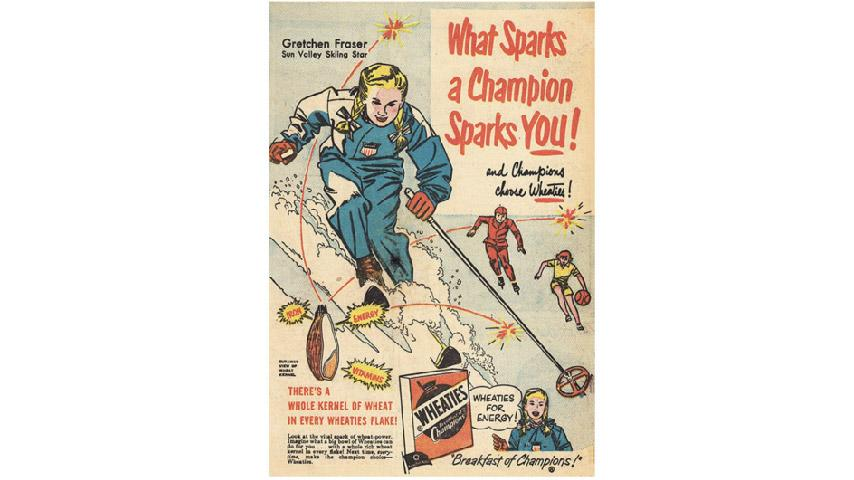

Gretchen Kunigk Fraser ’41 showing off her two Olympic medals from St. Moritz: a gold in slalom and a silver in alpine combined. Photo courtesy Tacoma Public Library.  Her accomplishments landed her on the cover of a Wheaties box. Image courtesy of Rick Just/Speaking of Idaho

Her accomplishments landed her on the cover of a Wheaties box. Image courtesy of Rick Just/Speaking of Idaho

Seventy-five years after Gretchen Fraser became the first American woman to win a medal in Olympic skiing, her legacy endures Sun Valley, where they named a restaurant after her, as well as a ski run, and erected a pair of statues in her honor. But as a man named John Bechtholt soon discovered, outside of Sun Valley—and even in Bechtholt’s hometown of Tacoma—Fraser’s legacy had largely been forgotten.

Bechtholt, a frequent visitor to Sun Valley, picked up a copy of Luane Pfeifer’s book Gretchen’s Gold at a local Starbucks a few years ago and soon became obsessed with Fraser’s story. He went to the archival room of the Tacoma Public Library to read more, and realized they had no information about her. So he began collecting memorabilia and archiving articles about Fraser on his own. What he discovered was that, for a brief moment in the wake of her triumph in St. Moritz, Fraser was hailed as an American hero, her iconic pigtails depicted in advertisements and popular comic strips, adored for her All-American looks and her cheery demeanor, as well as her brilliance on the slopes.

But by 1982, when the Washington Post wrote an article about America’s first Olympic medalists in skiing, it didn’t even mention Fraser.

Over time, Bechtholt discovered there was a lot more to Fraser’s story than a single gold medal. In fact, beyond her brief dalliance with fame, she engaged in the kind of quiet heroism that Bechtholt and many others believe should not be forgotten—and, in fact, should earn her an enduring legacy in America’s Olympic history.

Gretchen Kunigk was born in Tacoma on Feb. 11, 1919, to a Norwegian mother and a German father who was the longtime head of the city’s water utility. Kunigk’s mother, Clara, had grown up skiing in Norway, and gave Gretchen her first pair of skis when she was 13, taking her to Mount Rainier’s Paradise Valley for her first ski trip. In the 1930s, skiing in America was still in its nascent stages; without even a rope tow to get up the hill, Gretchen and her brother would hike up, ski down, and hike back up. Soon after, Mount Rainier began to host ski races. Among the winners of one of those early races was Don Fraser, a University of Washington student who also worked at Boeing and who would be selected to compete in the 1936 Olympics in Germany, assuming he paid his own way there. (He made the money by working on a freighter, then injured his hip in practice and was unable to race.)

In the wake of those Olympics, skiing began to take hold in the Pacific Northwest and beyond—including at Puget Sound, where Kunigk joined the ski-racing team as a student from 1937 to 1939. At the same time, Mount Rainier attracted a key visitor: Otto Lang, an instructor at a prestigious ski school in Austria, who came to the mountain to film an instructional movie and was so taken by it that he opened a ski school. And then he discovered his star pupil: Gretchen Kunigk. “In a very short time, I detected that this young lady had the determination and the doggedness to go places,” Lang would say.

In 1937, the 18-year-old Kunigk got her first big break: 20th Century Fox wanted to film a movie with the actress and former figure skater Sonja Henie that featured the hot new sport of downhill skiing. But they needed a double, and contacted Lang, who suggested Gretchen could do the job. The movie, starring Henie and Tyrone Power, was called Thin Ice, and it was enough of a hit that it helped promote skiing to the masses of Americans who were just becoming acquainted with it and began to view it as a destination sport.

Among the epicenters of that ski boom in America was Sun Valley, Idaho, a small resort town that began to attract a crowd of movers and shakers from business, politics, and Hollywood. In 1938, Gretchen and Don Fraser—who had been competing side-by side in Pacific Northwest ski races for the past couple of years—rode the train from Seattle to Idaho for the Harriman Cup, a relatively new competition that gathered some of the best ski racers in America at Sun Valley. Neither of them won any events, but a year later, they got married.

In Sun Valley, Fraser served as Henie’s double in another ski movie, Sun Valley Serenade. She and Don moved to Denver, where after the 1940 Olympics were canceled due to the war in Europe, Gretchen would win the national championship in two events in 1941. When Don went off to serve in the Navy, Gretchen took flying lessons and earned her pilot’s license. Lang began making a series of patriotic films and asked Gretchen to ski for Henie in Utah, where she saw something that would change the course of her life. After meeting amputees returning from the war at a nearby hospital, Fraser became determined to teach them to ski.

“I had no idea how to do it,” she later admitted. “I just figured there must be a way to help them enjoy life again and show them confidence.”

As the war ended and the 1948 Olympics approached, Fraser figured her competitive skiing career was probably over. But Don urged her to attend the tryouts in Sun Valley; she referred to herself, only half-jokingly, as a “retread.” Still, she managed to beat out 14-year-old phenom Andrea Mead and win a place on the team. She boarded a train from Seattle to New York, sailed across the Atlantic, took a train to Paris, and spent two days on a narrow train riding up the mountain to St. Moritz. “She is blonde, pretty, proficient, and strangely inclined to humbleness,” one reporter wrote of Fraser after she won the gold medal, and when she finally made it back to the United States after her victory, she was feted as an All-American hero.

In New York, Sonja Henie threw a party celebrating America’s two newest gold medalists, Fraser and ice skater Dick Button. When Fraser returned to the West, she was honored in Portland and Tacoma; in Vancouver, Wash., they held a parade for their newest local hero, with dozens of local girls doing their hair up in pigtails like Fraser’s. Advertisers jockeyed for her endorsements; in addition to promoting the Union Pacific resort in Sun Valley, Fraser signed deals with Wheaties, where she appeared on trading cards and cereal boxes, and the sportswear company Jantzen. She appeared in dozens of comic books, as well, and traveled to Norway to visit her mother’s relatives and meet the prince of the country.

But one of Fraser’s first stops upon her return home set the tone for how she viewed her obligations, both as an Olympic medalist and able-bodied athlete. She went to Barnes General Hospital in Vancouver and visited injured veterans. Eventually, she would start a program for disabled skiers in Portland called the Flying Outriggers; she also became an honorary chairman of the Special Olympics. When 16-year-old Sun Valley ski racer Muffy Davis was paralyzed in a ski training accident in 1989, Fraser showered Davis with gifts and encouragement, including a four-leaf clover pin that the founder of Sun Valley, Averell Harriman, had given to Fraser before the 1948 Olympics.

In an interview with Ski magazine, Davis said Fraser told her the pin had brought her good fortune, and she wanted to pass the luck on—and apparently it worked, as Davis went on to win seven Paralympic medals in skiing and cycling, and later served in the Idaho state legislature. “If you accept and take advantages offered by a community or country,” Fraser wrote to herself in papers found after her death, “you give of volunteer time and money in return for that privilege.”

Fraser spent four years after the 1948 Olympics as an ambassador and endorser. And then she gave up that public profile in order to spend time raising her family and pursuing the causes she was passionate about. “I did what I could to help out our business,” she later told the Columbian newspaper. “I had a contract [for endorsements], but I had to be an All-American girl. I never smoked anyway, but that was one of the things the contract didn’t allow.”

Over the course of her retirement, as she retreated from the public eye, Fraser’s fame began to dim. She joked that one magazine article about her “said something like, ‘I won the first American medals, had a child, and went back home to oblivion.’” Her life may have quieted, but it was anything but pedestrian: After serving as manager of the Olympic ski team in 1952, she continued to fly planes (famed pilot Chuck Yeager was among her mentors), continued to work with disabled skiers, continued to indulge her passion for horses by serving on the Olympic equestrian committee, and continued to promote skiing at home and abroad. She was inducted into the Puget Sound Athletic Hall of Fame in 1989. She died in Sun Valley at the age of 75, in 1994, just a few weeks after her husband.

As he continues to study the details and gather mementos from Fraser’s career, Bechholt presumes—as many others have—that Fraser was overlooked for decades in large part because of her gender. And he’s hoping that will change for future generations, particularly in the town where she grew up and at the college she attended. He’s given away some of his materials to both the Tacoma Public Library and the Tacoma Historical Society, and as he seeks a home for the remainder of his collection, he’s hoping Fraser’s story will be told over and over again.

There are two larger-than-life-sized bronze statues of Gretchen Fraser, the first American to win an Olympic ski medal, in Sun Valley, Idaho

“It was just shocking to me—she’s the most celebrated and achieved athlete to come out of Tacoma,” Bechtholt says. “And no one had heard about her.”