Homesteading in Pend Oreille County

July 1, 2023 at 9:28 p.m.

Dorothea in 1916 and Dorothea in 2003

Dorothea in 1916 and Dorothea in 2003

Dorothea (Pfister) Nordtrand (1916-2011) was a frequent contributor to Northwest Prime Time. Her essays also appear in HistoryLink.org’s “People’s History Library.”

This story of her family’s homesteading years in the northeast corner of Washington state near Tiger is Part I of a continuing series that will appear once a month or so at www.NorthwestPrimeTime.com.

The Tiger Tale

I was born in Tiger, Washington state, in 1916, the third child of Joseph and Mary Pfister. In 1911, they had taken a homestead claim to what they always later called a stump- or rock-ranch, half-way up the side of Tiger Hill.

Mother had suffered a near-fatal bout with diphtheria, and they were forced to make a new home in an environment more healthful for her than where they had been living, the damp, coastal area of Western Washington.

Then, in 1910, the government opened up an area of Pend Oreille County, in the northeastern-most corner of Washington state, to homesteading. The area had become accessible with the completion of the railroad through what had been dense woodland. Tiger boasted a daily train, whose main function was to carry logs, cut from the surrounding forest, to Spokane, 125 miles to the southwest. The whistle of the train down in the valley could be heard far up into the mountains and made a link with civilization for the people living there.

Daddy and Uncle John Gierhofer, Mother's older brother, each took claim to an 80-acre tract, on which they were obligated to build and work the land for 10 years in order to get title. Part of the government's program to coax homesteaders onto the land was the promise of free seeds each year. Other than that, their living was entirely their own responsibility. The opportunity for "free" land in a climate both high and dry, as prescribed for Mother's weakened chest, must have seemed an answer to their prayers. Dad and Uncle John were young, strong and able. Mother's health did, indeed, improve in the mountain air.

Log Cabin Days

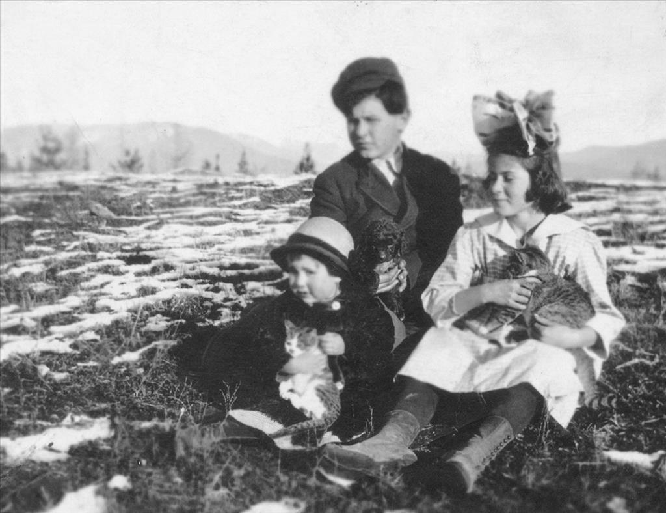

The Pfister log home, Tiger, Washington, ca. 1910,

The Pfister log home, Tiger, Washington, ca. 1910, photo courtesy Dorothea Nordstrand

The land they chose to homestead was covered with heavy forest, but within reasonable reach of tiny Tiger Town by horse and wagon. My father and Uncle John built our cabin and Uncle John's from logs cut from the timber growing on the claims. Daddy and Mom took my brother, Jack (John Joseph), who was four years old, and my two-year-old sister, Florence, to this wilderness.

I'm very proud of my pioneering parents. They grew most of their food on their little farm, but had no money crop, so my father and uncle found work at one of the nearby logging operations while Mother kept the farm. Dad was only able to get home on weekends, so most of the burden of caring for the family fell on her youthful shoulders. Mother was only 25; Dad and Uncle John were each 27. Uncle John and my parents were very close—I'm sure Dad would have counted John his best friend. The bond between Mom and her brother was always very strong.

Our cabin was quite simple. There was a main room, which served as a living room, a kitchen in an ell off the big room, and an open loft above, where the kids slept. A steep stairway opened into the loft, with shelves built into the space behind the stairs. There were also two little lean-to rooms. One of these was a bedroom for Mom and Dad. The other was usually occupied by whoever was the current schoolteacher. A long, open corridor along one end served as a place to cool milk and butter. It was here that pans of rich milk from our Jersey cow were left for the cream to rise to the top to be skimmed for butter. This part of the house was never heated and became very cold during the winter. There was a porch along the front. Heat was from the kitchen wood stove and a small, black, pot-bellied stove in the main room.

Conveniences and Amenities

There were no frills. However, by local standards, this cabin was better than most. Ours was the only dwelling with screens on windows and doors. It was the only one that had running water in the kitchen. The others had pumps and wells near the kitchen door. Dad put a ram into the fast-flowing creek that ran down our hill that pumped water into a cistern in the attic. From there, gravity fed it to the faucet in our kitchen sink. Hot water was heated on the kitchen stove. Dad contrived a way to have any overflow piped to the animal's trough near the barn. He had a logical, innovative mind.

For the laundry, he built Mom a long bench with room for a washtub on each end. It had a divider across the middle, where she attached the wringer, a contraption with gears that rolled two hard rubber rollers against each other by means of a sturdy handle at one end. First, the soiled clothes were scrubbed clean using the scrub board, a wooden frame holding crimped metal to rub against. Then, the clean clothes were fed into one side of the wringer from the hot-water-and-soap tub and dropped from the other side into the rinse-tub. The scrub-tub was then replaced by a clothes basket and the rinsed clothes were put through the wringer again. White clothes were boiled in the copper boiler that steamed on the stove.

In winter, this cumbersome operation was carried on within the corridor. Of course, all the water was heated on the kitchen stove and carried to the tubs in large metal buckets. Whenever the weather would permit, the bench would be taken out into the yard, and the work done there. The clean clothes were pegged onto a long clothesline with wooden clothespins. These looked like small dolls with no arms, as there was a knob on the end like a head, and the two grippers looked like legs. We used to "play dolls" with the clothespins, wrapping them with yarn or bits of cloth for clothes. Many of Mother's clothespins had small faces drawn onto the knob-ends by us children.

Our cooler was a screened series of shelves built onto the shady, north side of the cabin. Some of the neighbors had wooden boxes sunk into the creek where the cool mountain water would flow around the perishables. Occasionally, an early spring run-off would take box and all down into the valley.

Life in the Forest

A rifle rested on pegs over the kitchen door. Coyotes might come for the chickens. Also, there were cougars in the neighborhood. Dad taught Mom to use the gun. He used to say she was as good with it as he was. She needed the rifle for security during the many times when she was alone except for the children.

Dad and John hunted to make a change from the occasional pork and beef they raised. Mom would preserve the meat and make sausages, using salt-brine. Our root cellar was a cave-like excavation into the hillside near the kitchen, deep enough inside for an adult to stand upright. It had a sturdy wooden door. Inside there were shelves to hold the jars of canned food and the boxes of fruit and vegetables. On the dirt floor stood wooden barrels of preserved meat, dill pickles, and sauerkraut.

Even the children helped with the food. Mom knew how to use almost everything from the land. Once, however, she made a mistake with mushrooms; the ones she gathered were poisonous. We were all very, very ill.

There was no church near us, but religion was taught by the schoolteacher at Forest Home School. The children really cherished the pretty, colored pictures that were part of the Sunday school lessons. The schoolhouse was the center of the community. Holiday celebrations were held there.

Florence Goes to School

When Jack was old enough to go to school, Florence was lonesome and begged to go to school, too. The teacher, Miss Granstrand, finally agreed to let her come. Thrilled, Florence went with Jack, carrying her lunch in a paper bag, like the "big kids." The school was one big room, with one or two students in each grade ... 18 or 20 altogether.

It was a long time until lunch. Time began to drag. Seeing the other children raise their hands for attention, Florence raised hers and told Miss Granstrand she was too hot. The teacher opened a window. Pretty soon, another hand ... still too hot. The teacher opened another window. On the third hand, Florence was told to go sit on the porch. She was bored there, too, so climbed under the porch, but it was full of spiders. Lunchtime was fine, but over too soon. After that, time really crawled. The next morning, she was glad to stay home.

Florence remembers going with Dad to Spokane on the train when they needed supplies not available in Tiger or Ione, the next nearest town. They stayed overnight at the St. Regis Hotel. A big treat was to go to the Natatorium Park and ride the Dragon Ride, a roller-coaster. Another treat in Spokane was to pick up odd-shaped rocks from the riverbed. I remember one that was shaped like a doll and another that was a very recognizable rabbit. They were made flat and smooth by the river and were very pleasant playthings.

Daddy's Pies

Daddy worked as a cook at the logging camp. Once, during that time, Mother and the kids came to visit him. He was making pies for the loggers' dinner. Somehow, he managed to get into the salt instead of the sugar, so he turned out some mighty unpleasant pies. Shortly after that, he used to say, the company put him to driving a log wagon with a four-horse team from the woods camp into Tiger Town to meet the train. He liked driving a whole lot better than working around camp.

There were no doctors. Once, a pig grabbed Mother's thumb and nearly bit it off. One of the neighbors helped her put it back together and bandage it. It healed perfectly, and she kept the use of it. Another time, Jack and Florence were playing "baseball,” using a mop handle for a bat. When Jack hit the ball, Florence ran right into the metal end of the stick and split her forehead open. She has a scar to show for it, not very big, considering the severity of the wound. When Dad had a bout of pleurisy, making his chest so painful he could hardly breathe, Mom applied mustard plasters, renewing them as they cooled, until the inflammation in his lungs was gone.

Neighborly Friends

Neighbors were not exactly close by but were good friends for all of that. Uncle John lived across a deep ravine where we could see his cabin from ours. Beyond him, lived the Peltiers, a French couple with no children. Mr. Peltier is fondly remembered for his luxuriant handlebar moustache.

Near the Peltiers lived the Lasswells with their four daughters. Mrs. Lasswell kept goats and was very generous with the milk. Dad hated goats and goat milk, but to be polite, he would drink some. About that time, the goat would get up and walk on the table and he would nearly upchuck. Mrs. Lasswell was pretty casual about her goats.

Along the road leading to town lived the O'Neills, who ran the general store in Tiger. Jerry O'Neill was godfather at my christening. There was no church nearby, so we all went by horse and wagon to Newport, many miles away, for my christening.

Next to the O'Neill's house was the Isham's house with their big family. There is a picture of me as a small baby taken in front of a row of sweetpeas in their yard. Beyond the Isham's were the Blairs with their son, Hustey. Mrs. Blair always had apple jelly sandwiches for any hungry child who came her way. The Beldens owned a big, fairly prosperous farm and kept guinea-hens for "watch-dogs." The Tremblays were a large family. There were 12 children, including the twins, Pansy and Daisy, with whom I slept my one and only night in a hay-mow. It was itchy!

Housework at the Homestead

Once or twice a year, Mom would hitch the two horses to our wagon and drive into Ione for staples, a round trip of about 10 miles. She usually bought large bags of flour and sugar, and a huge can of Postum. I don't remember ever having coffee in the house when I was growing up. As a great treat, she would buy a box of graham crackers iced with pink or white frosting. How we would enjoy those!

Between times, she would trade for absolute necessities at the Tiger store, using her homemade butter for barter. She also sold eggs and butter to our neighbors for what she called "pin money."

In September, she would hitch up again and drive to the original Kettle Falls, which is now under Lake Roosevelt. She bought boxes of Gravenstein and King apples to put into the root cellar for winter and other fruit to can. We had no fruit trees on the homestead, as the growing season was too short. We did have raspberries, strawberries, gooseberries, and black caps.

Florence Early lived in the town of Tiger. She was a musician who wrote a ballad, "Ponderay Sunset," which was actually published. A copy of the sheet music was one of our family treasures for many years. Mrs. Early took us into her home during the winter I was born, as the snow was too deep to allow Mother to stay at home on the mountain until time for my birth in February.

Dorothea is Born

Mother had been warned not to have more children after my sister's birth because of the weakness left from her near brush with death from diphtheria, so it must have been a scary time for her. Because of that, a doctor came 125 miles from Spokane to attend my birth. Mother told me that my birthweight was less than four pounds and my first bed was a shoebox. She also told me that she tied me to a pillow with a diaper, because I was so small I was hard to handle. They named me Dorothea Mary.

Of course, the older children had their chores: gathering eggs, weeding the garden, helping with the animals, and keeping the wood boxes full. The one chore they both hated was keeping the pasture free of Jim Hill mustard, a weed that would have taken over the land if left alone. It was a never-ending nuisance.

Dandy and Barney

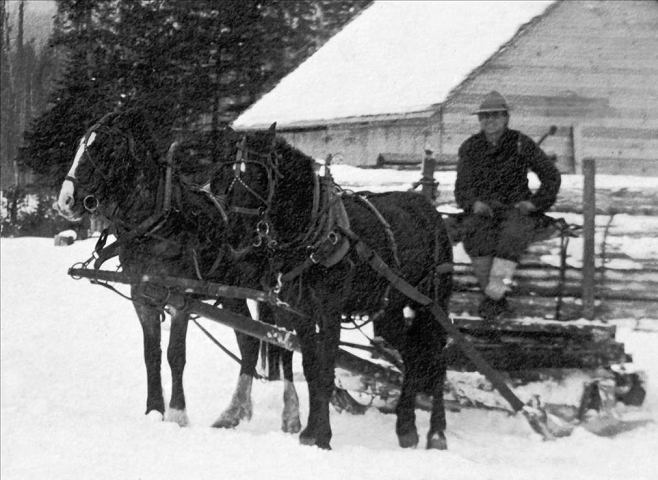

Dorothea’s father, Joseph Pfister, in Tiger, Washington, ca. 1915

Dorothea’s father, Joseph Pfister, in Tiger, Washington, ca. 1915Photo courtesy Dorothea Nordstrand

He helped Dad with his hunting. He would point his ears in the direction of a deer, rather like a hunting-dog on point. Dandy must have had a sense of humor. Dad loved to tell about the time he tried to make Dandy pull a plow. Dandy didn't want to pull a plow, so he picked Dad up by the seat of his pants and dunked him into the horse trough! Dad's brown eyes would twinkle and he would chuckle as he told the story. Daddy's wonderful sense of humor is one of the greatest things I remember from my childhood.

Our second horse was a black named Barney. Jack and Florence rode him to school through the woods, four miles each way, even in the deep snow of winter.

Hard Winters

The bitter, winter weather left marks on all three children. For many years after we left Tiger for the mild climate of Seattle, Florence and Jack suffered from chilblains on their feet. My discomfort was also chilblains, but mine was in my hands, which would swell, ache, and itch. Mine stemmed from a day when I lost my mittens in the snow while being pulled around in a homemade sled with a box on it, and my fingers became slightly frostbitten. I remember how my hands hurt that day, although I wasn’t much more than two years old. It really hurt!

The winter of 1916, when the family moved into Tiger Town for my impending birth, they lost their beloved dog, Casey. He was a small, fox-terrier-type dog, white with black and brown markings. His main claim to fame was his trick of taking a running leap and grabbing onto the dangling legs of Dad's longjohns, as they hung on the clothesline. The line was on a pulley so Mom could stand in one place and hang the wet clothes and then send them out over the ravine to get the best breeze. Casey's flying jump would take him and the longjohns careening out over a considerable drop, where he would hang until rescued. He must have got some special kind of doggie thrill out of it, because he never learned not to do it.

The winter of 1918 was the time of the terrible influenza epidemic. Thousands of people all over the country died. Dad was working at the logging camp and many of the loggers came down with the illness. When he became sick, the company wanted him to go home but he refused to do so, not wanting to take the illness to his family. Many of the men who did go home died and took their families with them.

Coogan with Cream

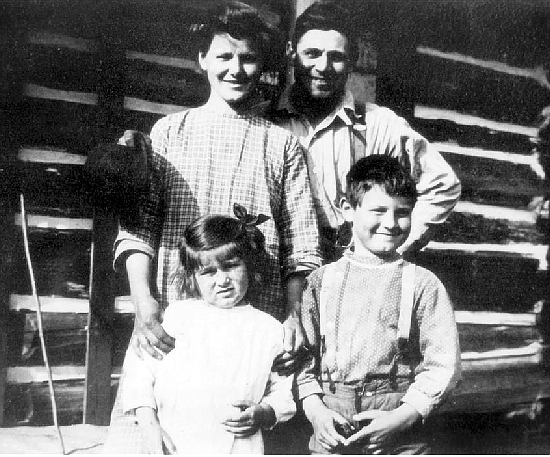

Jack, Florence, and Dorothea Pfister, Tiger, Washington, ca. 1918.

Jack, Florence, and Dorothea Pfister, Tiger, Washington, ca. 1918.Photo courtesy Dorothea Nordstrand.

Florence tells of the time when Mom, working in the garden, suddenly realized she hadn't seen me in some time. On going into the house, there she found me, sitting on the bedroom floor and, with a pair of scissors, cutting the fringe off the new bedspread she had just bought from Sears & Roebuck. We had that shorn spread for years. I don't remember ever feeling guilty, though I should have. Anything new was a real luxury during those lean times, and Mom must have been heartbroken.

Mother baked all the bread and cooked nearly every mouthful of food that fed her family during the 10 years spent near Tiger. In later years, she excused her store-bought cookies and bread by saying she had baked enough for the rest of her lifetime during those years on the farm.

Several things happened to us in 1918. I swallowed an open "beauty pin," (a sort of safety-pin made of twisted copper wire) and had to go several days with nothing to drink and nothing to eat except soda-crackers, until the cussed thing passed through. I'm told I cried for something to drink, but it was necessary to let the crackers form a ball around the pin so that the sharp point would not pierce my intestines. Try explaining that to a two-year-old.

Florence's Adventures

My Grandfather Gierhofer was very ill. Mother brought us children to Seattle to see him before he died, and Florence stayed on, for what was left of the schoolyear, with Mother’s sister, Aunt Ida and Uncle Jim Nolan. She attended her first city school, Ross School, near their home in the Fremont-Ross district. When school was out, Ida and Jim drove her home to Tiger in their touring car.

Florence remembers that Ida and Jim gave her a white teddy-bear, whose red eyes lit up when a button in his back was pushed. They also gave her a live rabbit. Somewhere in Eastern Washington, they let the rabbit out to eat, and it took off through the sagebrush. Jim chased it with his long legs flying, and finally was able to catch it. It stayed in its cage the rest of the trip.

They stopped for a picnic. Needing some water, Jim unscrewed a pipe leading to an irrigation system. The water shot far across the field and he was not able to reattach it, so they took off hurriedly, without their picnic.

Moving On

When we left the homestead, after those 10 hard years, we were able to sell the place to a man named "Schlister" ("Pfister-to-Schlister" was a joke in our family), for $400.00, a small price considering the time and hard labor involved in gaining title.

Materially, the years on the ranch were unprofitable. However, and this was the real value: Mother had become well and strong again. The only reminder left from her nearly fatal illness was a little, soft cough, with which she greeted every morning for the rest of her life.

Next month, look for another essay from the Dorothea Nordstrand collection.