The Legacy of Japanese American Farmers in the Sammamish Valley Fights to Live On

August 15, 2023 at 3:39 p.m.

Content warning: Anti-Japanese racism, war, suicide. This article is courtesy of Woodinville Weekly, which originally ran the story November 2022. All photos courtesy of Funai Farm.

“My dad and uncles were fighting for the United States Army in Italy, France and Germany while their families were behind barbed wire.”

Harvey Funai is a third-generation Japanese American (Sansei) farmer who operates Funai Farm in the Sammamish Valley. His paternal grandparents opened the farm not long after immigrating to the U.S. in the 1930s. They had eight children.

Harvey’s grandparents Kane and Kametaro Funai and their eight children (including Harvey’s father)

Harvey’s grandparents Kane and Kametaro Funai and their eight children (including Harvey’s father)

On Feb. 19, 1942–81 years ago–the Funai family were forced to bear “one of the most shameful moments in American history,” as it was described in a recent Presidential National Day of Remembrance statement: President Franklin Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066, that called for the internment of virtually all Japanese Americans in concentration camps. The decree remained in effect until the end of World War II.

But this is not the only story of the Funai family during the war. Harvey’s dad, Toshio, and three of his uncles, George, Aubrey and Frank, enlisted to fight for the U.S. Army while their parents were imprisoned in the Minidoka camp in Idaho.

The brothers joined the 100th Battalion/442nd Infantry Regiment, which would go on to become the most decorated regiment in U.S. military history. It was made up almost entirely of young, second-generation Japanese American (Nisei) men whose families were imprisoned in the camps.

"Dad was awarded the Bronze Star Medal, with ‘V’ for Valor, and a Congressional Gold Medal that was given to those still alive many years later and who served in the 442nd/100th/Military Intelligence Corps.,” Harvey wrote in one of his weekly emails, which he sends out to Funai Farm’s returning customers.

Uncle George, 29 at the time, was a member of Company K, one of several units that saved the Texas National Guard, the “Lost Battalion”, who were surrounded by German forces in the Vosges Mountains in France.

The 442nd suffered heavy casualties before they broke through the German line. George was captured and held prisoner. One German soldier wanted to shoot him, but another talked them out of it and helped George escape.

"They lost more men than the men that they saved,” Harvey said. “And the sentiment of the Japanese American soldiers was, if it was reversed–if they were the ones surrounded by Germans and trapped–that nobody would have attempted to come rescue them.”

After the war, the Funai brothers returned home to learn that their mother had taken her own life in the concentration camp.

"They never expressed any bitterness,” Harvey said. “The fact that my dad and family were never bitter or angry, at least not in front of any of us, is a testament to their determination to be viewed as good American citizens and not bring any shame to the family.”

Fresh produce is the star of Funai Farm

Fresh produce is the star of Funai Farm

“When the family came back from camp, finally, to start farming again and start their lives over again, the White people would not buy produce or things from the Japs,” he continued. “And so the local minister, who was White, would dress up in overalls, and he would take our family’s produce to Pike Place Market and sell it for them so that they could have money to live on.”

The ladder is a well-known staple of Funai Farm. It sits by the entrance when the farm is open for business.

The ladder is a well-known staple of Funai Farm. It sits by the entrance when the farm is open for business.

Today, Harvey Funai, 69 years old, continues to operate the farm in his family’s name. Though he already has a 38-year career with the State of Washington behind him–during which he worked for the Washington State Health Care Authority and the DSHS; and coordinated and oversaw major minority affairs, sexual orientation, disability and tribal affairs initiatives–Harvey still chooses to work full time to run the two-acre farm.

“I can tell you the whole life story of each corn, or beet, or carrot, or green bean or whatever it is that I picked, because I'm the one that planted the seed, I'm the one that weeded it, and cultivated it, and nurtured it, and then picked it, and brought it up here and I'm selling it to you,” he said.

When I visited the farm, everyone who came by during the 90 minutes I was there had already been to the farm many times before, except for two customers, whom Harvey was quick to become acquainted with. He masterfully moved through small talk to make a deeper connection with one of the men; they chatted about responsible farming practices (the customer was a beekeeper), national identity (he had immigrated from Russia about 15 years ago) and spirituality (he was devoutly Christian). A customer named Mark Jenkins said he has been purchasing produce at the farm since Toshio was the owner over 20 years ago.

Two things keep Mark coming back, he said: the sweet corn, and Harvey’s weekly emails.

Harvey insisted I try the corn raw–a sort of initiation ritual for new customers. It was deliciously crisp.

“If you buy corn from the store, don’t bite it raw like you do here,” Harvey said. He explained that he doesn’t use insecticides or sprays on his crops. Uncles Aubrey and Kart worked in farms where those products were used heavily, and each died younger than Harvey is now.

“If you can’t trust your local farmer, who can you trust?” Harvey said.

Customers throw cash in a bucket to pay for their produce. Some pay with bills much larger than the cost of what they buy; a few pay less, but the tips of the higher payers much more than cover for these customers.

Funai Farm gives food to Asian Counseling and Referral Service (ACRS), an organization which aids Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

Funai Farm gives food to Asian Counseling and Referral Service (ACRS), an organization which aids Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

Kerry and Carmon Comunale said they have been buying produce at Funai Farm for more than 10 years.

“He always informs us,” Kerry said–yet another mention of Harvey’s iconic emails. “And the pumpkins are always amazingly good.”

***

Sept. 11, 2018: “Thank you to Everyone for the treats, bags, tips, and words of support. If you haven't tried our carrots yet, the running joke is they are so sweet because we irrigate with sugar water. I always tell customers to grab a bunch of our carrots before you grab your corn because we will run out of carrots before we do corn. We will have sweet white corn, large bunches of beets, carrots, Swiss chard, very limited amount of pole beans and kale, Italian prunes, possibly champagne grapes, and I need to start hauling up some pumpkins and squash.”

…

“Dad has been in the hospital since last Wednesday. He had a 103 temperature and I had to drive him to the hospital, which was nerve wracking. He was diagnosed with an infection, pneumonia, and heart beat out of whack. Miraculously, he made it to his 96th birthday on September 9th. He is slowly improving and ate his first food, apple sauce and pudding for dinner today. Dad and Uncle Aub taught me how to be a farmer when I was a kid; and, the other farmers referred to me as ‘the little farmer of the valley.’”

***

Sept. 13, 2022: “This past week, Dad and Mom would have been 100 and 97, respectively. They celebrated their 72nd wedding anniversary together and passed shortly thereafter and less than a month apart from each other. My siblings and I were born under a lucky star to have such wonderful and incredible parents. They met at the Minidoka Concentration Camp when dad and his brothers were visiting family members.”

***

Harvey’s mom died in December 2018, and his dad in January 2019.

“I hope that it brought them some peace of mind and comfort, knowing that more than likely I would continue working the farm,” he said. “Now I’ve got a billion questions that I would love to ask my parents. And I think that’s true with most people when they lose their parents.”

Harvey intends to go on working the farm in his family’s name, not for financial reasons, but simply for the joy it brings him.

Harvey's grandparents’ grave marker

Harvey's grandparents’ grave marker

“I could literally make more money working at McDonald's,” he said. “But this is my life. This is my passion. This is my piece of heaven. And I continue doing this to honor my grandparents and my mom and dad.”

Funai Farm is located at 14209 Woodinville-Redmond Rd NE, Redmond, WA, 98052.

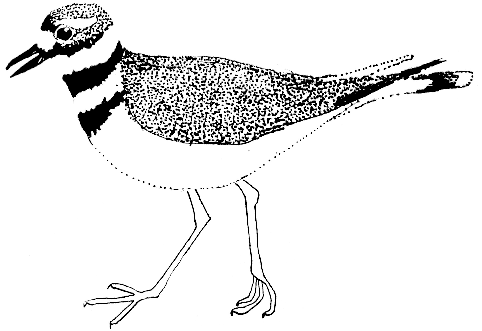

Editor’s Note: I was delighted to reconnect with Harvey Funai through a mutual friend. Harvey and I met at Western Washington University all those many years ago, but I never knew the story of what his family endured or even about the family farm. “The farm was the greatest place to grow up,” said Harvey of his childhood. Hearing his stories was so evocative, from his description of the sound of sprinklers sputtering out at night, to watching swallows fly across the corn on a summer evening, and how the newly fledged swallows would perch on the deck railing. “Mom just loved those barn swallows,” said Harvey. “They were like her little babies.” Harvey talked about the many animals seen on the farm over the years but none more special to him than the Killdeer that nest in his fields. He makes a point of finding where they are nesting and giving them a wide berth when he tills the fields for planting. He mentioned an early encounter while he was rototilling the field and saw a Killdeer in front of him that wouldn't move. He stopped and saw that not three feet in front was a nest with two eggs. He put a post in the ground to create a safe space for the nest. Later on, he noticed the nest had five eggs. I plan to visit Harvey at Funai Farm soon. I look forward to tasting the sweet corn, picking a bouquet of colorful flowers, and—just perhaps—catching a glimpse of the elusive Killdeer. –Michelle Roedell, Northwest Prime Time.

EDITOR'S UPDATE: I was able to make my first visit to Harvey's farm on Sin 2023. It was a beautiful, late summer day, made all the more special because I was with my childhood friends, Terri and Pat (left to right: Terri, Michelle, Pat). Harvey had originally contacted Terri, also a WWU alum, and I'm so grateful she connected us.

We ate raw sweet corn (delicious!), saw the rail where the baby swallows perched, and picked a bouquet of colorful flowers. We wandered the fields, picked beans, Swiss chard, kale and carrots. Then Harvey loaded us up with even more fresh produce. We had an amazing time at the farm, followed by a leisurely lunch. The only thing that could have added to the day's pleasure would have been a kildeer sighting. Maybe next time. Thank you, Harvey!

Harvey was a wonderful, charming, generous and hilarious host ,

Harvey was a wonderful, charming, generous and hilarious host ,