...by Brangien Davis / Crosscut.com

The 40,000-square-foot Fine Arts Pavilion, which prominent Seattle architect Paul Hayden Kirk designed with a jaunty accordioned roofline, boasted five galleries of visual art and cultural artifacts. (The building is now home to the Pacific Northwest Ballet.) Any one of the exhibits was a blockbuster show on its own, including the “Masterpieces” gallery showcasing Picasso, El Greco, Rembrandt, Monet and more one-name wonders.

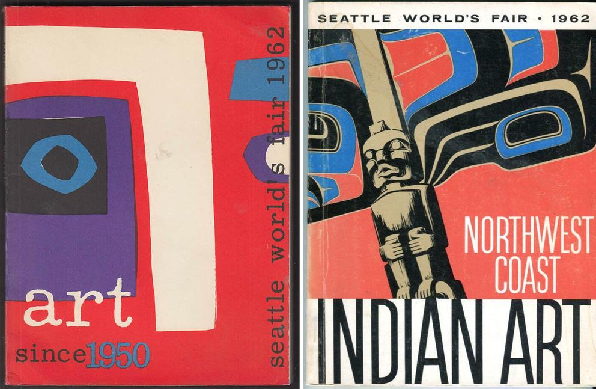

Art catalogs from the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, which featured a Fine Art Pavilion that showcased American and international art after 1950, Northwest contemporary art, old world masterpieces and an expansive collection of Northwest indigenous art.

Art catalogs from the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, which featured a Fine Art Pavilion that showcased American and international art after 1950, Northwest contemporary art, old world masterpieces and an expansive collection of Northwest indigenous art.

But not everyone was impressed by the array of art stars. Anne G. Todd, art critic of the Seattle Times at the time, noted that while the 50 works in the international “Art Since 1950” exhibit (which included Joan Miró, Henry Moore and Francis Bacon) “shouted” with “expressive vitality,” the contemporary American artworks relied on a “cynical emphasis on tricks and kicks” that caused them to seem “insolently aloof.”

Todd was much more impressed with the Fine Art Pavilion’s exhibit of “Northwest Indian Art,” curated by University of Washington anthropology professor and ethnobotanist Erna Gunther (who also served as director of what is now the Burke Museum). Previewing the show in the very first issue of ArtForum magazine (June 1962), Todd gushed, “It would be difficult to imagine more stunning proof of the expressive genius of the Northwest’s aboriginals.”

The exhibit included 330 works made by Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Nuxalk, Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, Nootka, Coast Salish and Chinook artists, including ceremonial robes, masks, totem poles, weavings and carvings. Gunther was hugely influential in raising awareness and appreciation of Northwest Indigenous art (one of her students was UW art historian Bill Holm, whose painted panels appeared on the walls surrounding the exhibit).

“The artwork of the Indians of the Northwest Coast is presented here with examples of the great arts of the world, both historic and contemporary,” Gunther noted in her exhibit guide, making the point that these works held their own on the grand stage alongside work by internationally celebrated artists.

In her review for The Seattle Times, Todd called the Native artworks “rare and splendid,” but felt the exhibit layout was given short shrift, “… as if it were a lobby decorated in a Northwest theme. A pity!” She also lamented a long-standing issue regarding displays of Indigenous artwork — the lack of readily accessible details about where each piece originated. Much of the tribal information was included in the catalog, but viewers had to pay extra to get one — which irked Todd, as did all the “page flipping” required.

After the festivities, the Fine Art Pavilion artworks were returned to museums and collectors. But the World’s Fair also included permanent artworks created specifically for the event — several of which can still be found at Seattle Center. Can you identify the Century 21 Expo artworks and architecture in the close-up photos above? (Check your answers below.)

One work that’s not included in this photo array is Seattle sculptor Everett DuPen’s Fountain of Creation, featuring several bronze sculptures he made for the fair. The plaza received a major overhaul in the early 1990s, when the kid-enticing wading pool and boulders were added. It’s currently under wraps while getting another makeover (big reveal due this summer), including restoration of the original sculptures: “Evolution of Man,” “Flight of the Gulls” and “Seaweed.” DuPen intended the group of works to evoke water’s critical role in nurturing plants, animals and humans on Earth.

While DuPen and other artists may have given nature a nod, the innovations showcased at the Seattle World’s Fair were largely about using science and technology to help man “harness nature’s forces” and “mold and control his environment,” as the guidebook put it.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring came out in June 1962, adding to a growing national conversation about protecting (rather than manhandling) the environment. It would be another eight years until the first Earth Day happened in 1970. But by the time Spokane held its own World’s Fair, Expo ’74, ecological concerns had shifted to front and center — evidenced by the motto: “Celebrating a Fresh New Environment.”

The 52nd annual Earth Day (April 22), and the need for that fresh new environment is stronger than ever. Consider commemorating the occasion with these environmentally themed art shows featuring local artists.

• Winston Wächter Gallery is featuring the surreal landscapes of Seattle painter Philip Govedare in Hinterlands (through May 30). These haunting bird’s-eye perspectives, often captured in unsettling reds and purples, reveal the ways in which both roads and rivers have ravaged the Earth.

• The King County Recology Artist in Residence Program (which I wrote about back in 2019) might sound like a dubious honor, as selected Seattle artists get their pick of materials from the town dump (specifically, the recycling center). But the results are always a testament to creative innovation. This year’s residents, Satpreet Kahlon and Lee Davignon, show the fruits of their foraging at Mutuus Studio in Georgetown.

• The group show Our Blue Planet: Global Visions of Water continues at Seattle Art Museum (through May 30; read my coverage from the opening).

• At Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle wood sculptor Dan Webb presents Burn (through May 14), a striking new series of meticulously carved and burned pieces featuring flowers, plants, cigarettes, and human hands. In his artist statement, Webb says it’s a show about “environmental disasters, endless forest fires, climate change,” but also about how the relationship between humans and nature is currently unclear, “the power dynamic undecided.”

• And at Traver Gallery, Seattle artist Marita Dingus has a new show of sculptures inspired by African art, the concept of reincarnation and the opportunities that abound in repurposing castoffs. Re-Souls (through April 30) showcases her special talent for refining refuse into expressive figures. Here, she uses electrical wire, license plates, brass keys, fabric scraps, rubber tubing, garage door hinges, guitar frets and whatever else she can “get her hands on,” she says, to craft this gathering of bodies. In her recent gallery talk, Dingus explained, “Art is the best way to celebrate culture … art is the celebration.”