Northwest Nebraska is full of surprises

September 1, 2020 at 6:00 a.m.

This summer, the road trip is being rediscovered by many travelers during what has become the new “normal.” They’re taking off in cars, campers, RVs and motorcycles, seeking opportunities to explore our country’s natural playgrounds.

Some are opting for the road less traveled in order to avoid potentially crowded areas. The upside to this plan is the potential of finding hidden gems along the way.

Take Northwest Nebraska, for example. Definitely not on my bucket list. But, the region was incorporated in the route I chose in order to reach my intended destination, the Dakotas. I expected a boring and dull ride through this section of the state, but instead encountered fascinating historical sites and geological wonders, as well as one very quirky roadside attraction.

My curiosity ended up taking me on a few detours, primarily to explore important landmarks for pioneers making their way out west during the mid-1800s. Tens of thousands of people traveled through this area, attracted to the forgiving terrain along the Platte River. The Oregon, California and Mormon Trails, and the Pony Express all used this passageway, making the route the “Main Street of America.”

Chimney Rock, located near Bayard, Nebraska, served as a point of reference and beacon of encouragement for the pioneers. It indicated the end of the plains and the beginning of the Rockies. With a peak that at one time measured 4,226 feet above sea level, it was the most recognized landmark on the Oregon Trail and impossible to miss. One pioneer aptly described this sentry of the plains as “Towering to the Heavens.” Fur trappers called it “The Chimney,” while others referred to it as, “Nose Mountain” or “The Smokestack.”

In 1956, Chimney Rock was designated a National Historic Site. And in 2006, it was depicted on the Nebraska State Quarter. The unique formation has come to symbolize the largest voluntary migration in the history of our country.

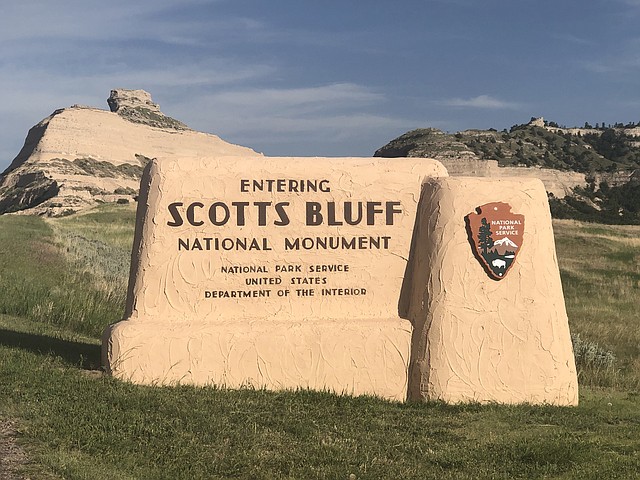

Another landmark along the Oregon Trail is Scotts Bluff, located near the town of Gering. Rising 800 feet above the North Platte River, this National Monument is named for fur trapper Hiram Scott, who died there in 1828. Different versions to the story of his death exist, but the prevailing tale says he was abandoned by his comrades, perhaps because he was seriously injured or ill. His bones were supposedly found near the North Platte River, though the exact site has never been located. Today, a plaque dedicated to his memory has been instilled along the North Overlook Trail on the summit of the bluff that bears his name.

The bluff was a prominent focal point for Native Americans before it became a trail marker for the emigrants who traveled westward, as well as for riders of the Pony Express. The pioneers knew for sure they had made it to western lands when they saw Scotts Bluff. The fortress-like formation gave them hope, as they knew that at least a third of the trail lay behind them.

Scotts Bluff National Monument preserves 3,000 acres of unique land formations that are in contrast to the otherwise flat prairie landscape. These geological features are comprised of sandstone, siltstone, volcanic ash and limestone, and have been weathered over time. Like Chimney Rock, they are slowly disappearing as a result of the forces of wind and water.

If you want to hike to the top of the bluff, take the three-mile out and back Saddle Rock Trail, which begins from the Visitor Center. As you walk, you’ll pass through different layers of the formation. When you reach the summit, there are a couple short spur paths, which provide picturesque views of the surrounding area. You can just imagine the covered wagons coming across the plains and the pioneers catching their first glimpse of this looming tower.

It’s also possible to drive the Summit Road up to the top if you prefer not to hike the trail. The road winds around and goes through a few tunnels before arriving at the Summit parking lot.

To learn more about the history of the North Platte Valley, as well as the area’s Native Americans and the country’s westward expansion, visit the nearby Legacy of the Plains Museum. Among the displays are pioneer artifacts, antique tractors and farm implements, an 80-acre working farm and historic farmstead.

About an hour away near Harrison, Nebraska, is Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, one of the most

prolific bone beds of the Great Age of Mammals. The area was set aside to preserve the unique paleontology of the area, as well as provide a venue to display and care for a noted collection of Native American artifacts.

Millions of years ago, when the land was a grassy savanna, prehistoric creatures such as the Dinohyus (a giant pig-like animal), Stenomylus (small gazelle-camel) and Menoceras (short rhino) ranged. They died during a period of climate change, which caused a massive drought. Hoofprints from these animals, as well as layers of fossilized bones can be found throughout the area.

There are two main excavation sites, Carnegie Hill and University Hill. The Fossil Hills Trail takes you to Carnegie Hill, where most of the digging took place in the early 1900s. Further down the road, the Devil’s Corkscrew Trail leads to the fossilized burrows of the small beaver Palaeocastor.

Unfortunately, with the Visitor Center closed, it’s impossible to view the collection of Native American artifacts.

And then there’s Carhenge. Though not an historic site nor a geologic formation, this roadside attraction is of interest simply because it’s so bizarre. This replica of England’s Stonehenge is located near Alliance, Nebraska. Instead of being constructed of large stones, as in the case of Stonehenge, it’s built from vintage American cars, covered with gray spray paint.

Carhenge was the brainchild of Jim Reinders and meant to be a memorial to his father. Reinders, a local man, had lived in England and was familiar with Stonehenge’s proportions and structure. When he returned home, he set about making his vision a reality. It involved rescuing 38 cars from nearby farms and dumps. The cars date from the 50s and 60s because their dimensions equaled those of the stones at Stonehenge.

Carhenge was dedicated in June 1987. However, it nearly didn’t survive, as the residents of Alliance thought it was an eyesore and wanted to tear it down. But, they eventually had a change of heart and now Alliance is the “Home of Carhenge.” It is regarded as a top roadside attraction and travelers come from all over to see it. And it has been featured in films, T.V. programs, music and books.

A visitor center has since been built at the site. There’s also an adjacent “Car Art Reserve,” where others have contributed sculptures made from cars and car parts, with names like, “Dino Dinosaur Skeleton,” “Spawning Salmon” and my favorite, “The Fourd Seasons.” The later is comprised of four cars standing on end in various colors and heights rising out of the ground. Each car represents one of the four seasonal stages of wheat grown in the area.

Carhenge is now owned by the city of Alliance, so it can be assured of future preservation, unlike Stonehenge, which is in a dilapidated state.

Debbie Stone is an established travel writer and columnist, who crosses the globe in search of unique destinations and experiences to share with her readers and listeners. She’s an avid explorer who welcomes new opportunities to increase awareness and enthusiasm for places, culture, food, history, nature, outdoor adventure, wellness and more. Her travels have taken her to nearly 100 countries spanning all seven continents, and her stories appear in numerous print and digital publications.