A journey through history along the Birmingham Civil Rights Trail

March 20, 2017 at 6:00 a.m.

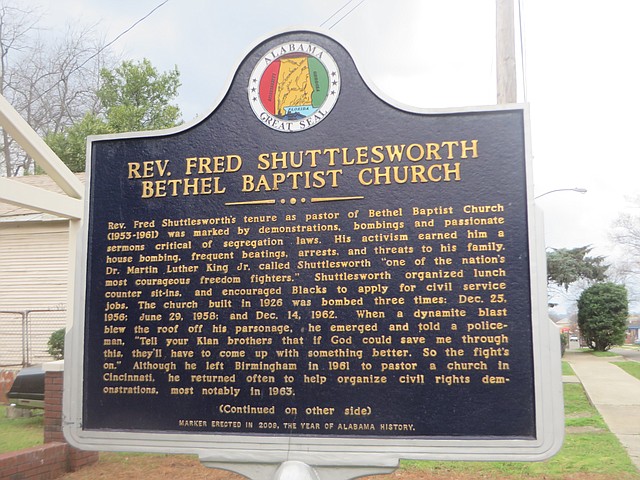

“It began at Bethel.” With these words, historian and educator Dr. Martha Bouyer proceeded to take me back in time to the birth of the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement. “The Movement,” as its members called it, started at Bethel Baptist Church, under the steerage of the church’s fiery pastor, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. It was Shuttlesworth who organized the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) after the State of Alabama declared the NAACP a foreign corporation which could no longer exist. This was in response to the Reverend’s refusal to turn over the names of the local members of the organization.

To many, Shuttlesworth’s name might be unfamiliar. I was unaware of this man’s contributions to the Civil Rights Movement until I visited Birmingham on an historical tourism trip. Shuttlesworth emerged as a “hidden figure,” who was often shadowed by other such well-known leaders of the time as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Reverend Ralph Abernathy. But, it was Shuttlesworth who initially galvanized the black community with the aim of dismantling the city’s segregation ordinances. He was the spark that created the flame.

The ACMHR was headquartered at Bethel Baptist Church. Built in 1926, this National Historic Landmark church and “American Treasure” served as a staging ground for the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement from 1956 to 1961. The church still stands within the neighborhood of Collegeville, despite having been the target of three separate bombings by white extremists. It withstood these attacks without ever missing a Sunday morning worship service, testament to the strength and enduring spirit of its pastor and his congregants. Shuttlesworth, who was known as the “Wild Man from Birmingham” by his colleagues, was the subject of countless attacks and beatings, and jailed more than any other civil rights minister. He is also said to have taken more cases to the U.S. Supreme Court than any other individual in the history of the court.

Every Monday night during these turbulent years, ACMHR mass meetings were held at Bethel and dozens of other churches scattered across the city. Ushers would take up collections to be used for bail to release those imprisoned for infractions against the Birmingham Segregation Codes. This could be anything and everything including talking too loud, “reckless eyeballing,” vagrancy, using the wrong toilet facilities or drinking fountains, or occupying the incorrect seating area on a streetcar or restaurant. Those convicted would go to jail and if they could not pay bail, they would end up in the “convict leasing” program, having to work their sentence off via hard labor. It was slavery by another name, as the offenders’ costs would continue to mount under various pretenses, with no end in sight to their imprisonment.

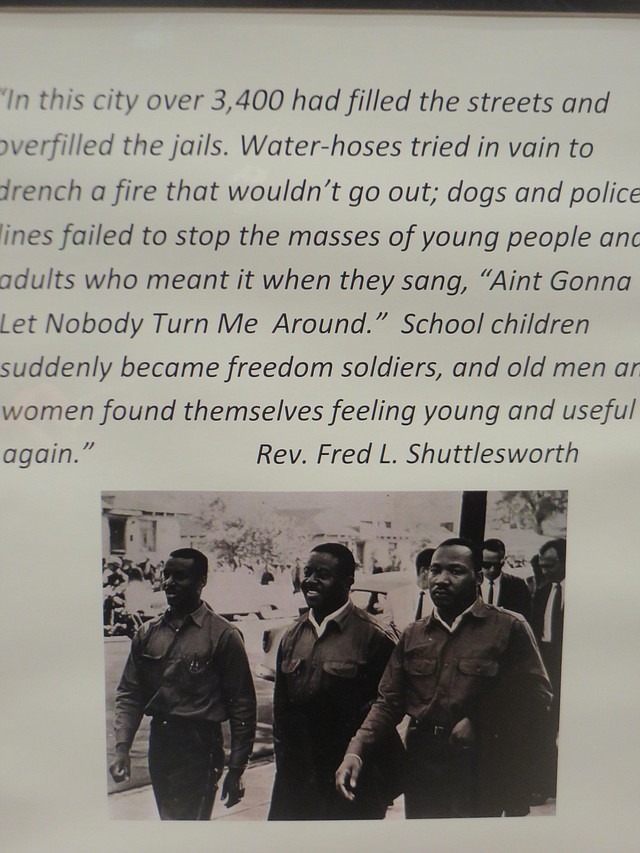

ACMHR was the strongest of the local civil rights movements, eventually merging together to form an umbrella group, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, under King’s leadership. Shuttlesworth invited King to join mass marches because King’s oratory attracted national media coverage. Birmingham became the catalyst for the most dramatic social and legal changes of the 20th century. The ensuing demonstrations and violence that occurred in this city ultimately led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ensuring equal access to public accommodations in America.

At Bethel, you’ll hear this story and learn of Shuttlesworth’s significant role, while having the opportunity to look at relevant photos, news articles and artifacts from the era. To set the scene, gospel music plays in the background, emphasizing the crucial question of the time, “Do you want your freedom?” Nearby on a counter is a jar of beans to illustrate one of the outlandish methods used to determine if a black person was eligible to vote. If the individual could guess the exact number of beans in the container, then he/she would be allowed to cast his/her vote. As this was nearly impossible, it almost guaranteed that blacks would not be able to participate in the process.

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church should also be on the list of places to include during your Birmingham Civil Rights tour. The church, a popular rallying point for the movement, became an obvious target for Klansmen. It is connected with one of the deadliest moments of the civil rights era. Days after a six-year court battle ended in favor of integrating Birmingham schools, four Klansmen retaliated. On September 15, 1963, they bombed the church, killing four girls (Addie Mae Collins, 14, Carol Denise McNair, 11, Carole Robertson, 14, and Cynthia Wesley, 14) who had been in the basement preparing for Sunday worship. Numerous others were injured. A short video, “Angels of Change,” explains the events of that day, while photos on display in the basement of the building show the damage of the dynamite blast. All but one of the stained glass windows in the church were destroyed. The damage that the sole remaining window incurred rendered the figure of Christ faceless. It is said that though terrorists tried to take away the vision of the movement, the body remained standing.

This incident burned a lasting impression around the country and all over the world, drawing overwhelming sympathy for the cause. There’s a marker at the site where the bomb was placed, as well as one at the front of the church, dedicated to the girls who perished. All four subsequently received Congressional Gold Medals. Two other black teens (Johnny Robinson, 16, and Robert Ware, 13) also died that same day, in separate incidents of violence.

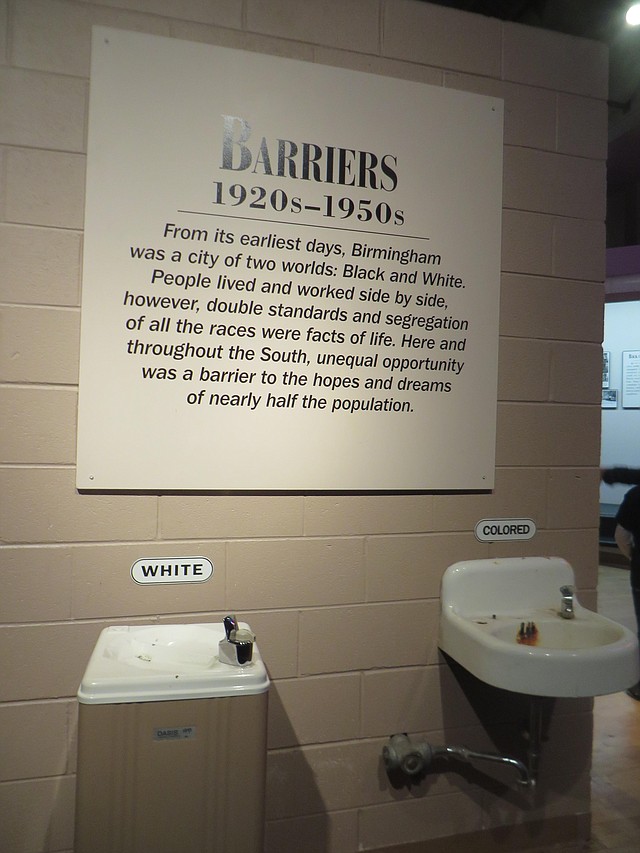

Across the street from the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church is the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Since its opening twenty-five years ago, over 2.5 million people have visited this impressive educational and interactive museum. Through photos, videos, audio recordings and exhibits, visitors are placed in the midst of the integration movement. In the Barriers Gallery for example, the cruel inequity of life for blacks living under segregation is conveyed, while in the Confrontation Gallery, voices of adults and children, both black and white, are heard saying things they would only share behind closed doors. The Movement Gallery takes you through the history of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement from 1954 to 1963, highlighting the Montgomery Bus Boycott and Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. A series of dramatic media presentations features the Freedom Rides, the history of the struggle to vote, the pivotal events in Birmingham in 1963, accompanied by actual news footage from the period, and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom with a large screen projection and audio including King’s stirring “I Have A Dream” speech.

Look for the original door from the jail cell where King wrote “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” that urged white religious bystanders to become active in the movement. There are also “white” and “colored” drinking fountains and a 1950s lunch counter that symbolized segregation in public places, along with a replica of a Greyhound bus that was torched because riders challenged the state’s segregation laws. Rosa Parks and others are given their due in regards to the contributions they made.

The Milestones Gallery contains life-size figures in a “walk to freedom” near a window view of Kelly Ingram Park, site of the 60s’ demonstrations. Images on the walls depict the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and chronicle the historic Selma-to-Montgomery March. Timelines note the advancements in civil rights made throughout the state and nation up to the opening of the institute in 1992.

A newly expanded gallery links the struggle for equality in Birmingham to movements for human rights throughout the world. There are displays on selected international human rights movements and stations where visitors can reflect and share their opinions about current issues. A focal point is the restored armored personnel vehicles used by the infamous Eugene “Bull” Connor. Connor, who was Commissioner of Public Safety for the city, became a symbol of institutional racism in his efforts to continue white supremacy.

Cross the street to continue your journey with a walk through historic Kelly Ingram Park, once the epicenter of the nation’s Civil Rights Movement. Blacks gathered in this public park in the spring of 1963 for rallies, marches and other acts of civil disobedience. It is here where Bull Connor directed the use of fire hoses and police attack dogs against the protestors, many of them children. These horrific scenes remain indelibly imprinted on the memories of those who saw the footage on televisions and in newspapers around the world. But, it was these very images that were instrumental in overturning legal segregation.

Called a “Place of Revolution and Reconciliation,” the park is now a peaceful spot with a number of artworks commemorating these events. The sculptures include two children seen through jail bars, a trio of praying ministers, the four girls who perished in the bomb at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and a statue of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Among the pieces are also potent depictions of police dog and fire hose assaults on demonstrators. In one area, visitors walk between two narrow structures that have sculptures of dogs violently lunging out of the walls in attack mode. For those interested, there is a mobile phone tour of the park’s statues, which interprets different civil rights events.

Though civil rights is definitely a major focus in the city, there are plenty of other attractions. Once an industrial town known for its iron and steel, Birmingham has developed through the decades into a sophisticated urban mecca with lovely designated outdoor spaces, hip and happening entertainment districts and an award-winning culinary scene.

Stop and smell the roses at the Birmingham Botanical Garden where gardens are planted according to themes, climb to the top of Vulcan, the largest cast-iron statue in the world, for a picturesque view of the city from atop Red Mountain, or hope on a Zyp shared bike and ride along established trails to the Saturday morning farmer’s market (April – December).

Two of the more unique sights include the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum, which boasts the world’s largest collection of motorcycles, and Sloss Furnaces, once a major iron factory and now a National Historic Landmark. With its web of pipes and towering smokestacks, it offers a glimpse into the great industrial past of the South.

When it comes to sustenance, know that you won’t go hungry in Birmingham. There are options galore from finger lickin’ BBQ joints and downhome Southern soul food cafes to lively Irish pubs and cozy French bistros. Later, check out the Lyric or Alabama theaters for some live music. As for your digs, Birmingham offers a range of accommodations to suit all budgets. To complement my trip’s focus on history, I stayed at the Hassinger Daniels Mansion Bed and Breakfast, a beautifully restored 1898 National Historic Registered Victorian mansion. It’s located in a desirable neighborhood and walking distance to an array of good restaurants.

For all things Birmingham: http:// www.visitbirmingham.com

Debbie Stone is a travel and lifestyle writer, who explores the globe in search of unique destinations and experiences to share with her readers. She’s an avid adventurer who welcomes new opportunities to increase awareness and enthusiasm for travel and cross-cultural connections. Her stories appear in a number of print publications as well as on various travel-oriented websites. Debbie is a longtime Seattle area resident, who currently resides in Santa Fe, New Mexico.