Find authentic Hawaii on Molokai

January 30, 2017 at 6:00 a.m.

Imagine a Hawaii with untouched beaches and an unspoiled countryside. No tall buildings, mega resorts, or malls. And nary a stoplight to be found. It’s hard to believe such a place exists, but it’s real and it’s Molokai, the “Friendly Isle.”

For many visitors to the islands, Molokai is off the beaten path and viewed with a bit of apprehension, mainly due to the fact they don’t know much about the place. They’ve heard it’s quiet and rural, and lacks the glitz and glamour of the other islands because residents frown upon major development. They’re right. But, that’s what makes Molokai so special. It’s authentic Hawaii – a place where the culture is thriving and where aloha is not just a word; it’s a way of life that speaks to the essence of the heart and passion of the people.

The residents of this small island work hard to protect and preserve their peaceful lifestyle because they love their land and their heritage. Visitors are always welcome, however, it helps to understand the power of these feelings and the need to respect them during your stay. Most who take the time to appreciate the indomitable spirit of the people will gain a deeper appreciation for the beauty and soul of the island. It also helps to have patience, as the pace moves slowly on Molokai, which is one of the reasons why folks come here. They want to escape their hectic urban existence and gladly welcome the opportunity to stop and smell the plumeria.

Molokai brings Hawaii’s history to life. Head to the sacred Halawa Valley for a trip back in time. This is one of the island’s most historic areas and its oldest inhabited location. It is believed ancient Polynesians settled here as early as 650 A.D. For many years, it was a center of taro patches and dozens of temples with a thriving populace. However, a pair of tsunamis in 1946 and 1957 swept up the valley and destroyed almost all of the homes, along with the fields.

Just getting to the valley is an adventure in itself, as the road is narrow and winding with blind curves, but there’s nonstop, jaw-dropping scenery to be admired at every juncture. Points of interest along the route include the ancient Hawaiian Fishponds, Kumimi Beach (a popular snorkeling spot), St. Joseph’s Church and Our Lady of Seven Sorrows (both built by Father Damien), Kalua’aha Church (Molokai’s first Christian church constructed in 1835), Halawa Beach Park and spectacular Halawa Bay.

Most locals come to the valley to fish, surf and enjoy the beaches. Visitors, however, make the trip in order to hike to Moa’ula Falls, which is accessible only as part of a guided cultural tour. The journey will take you into a verdant, lush rainforest covered in colorful, tropical flora before arriving at the picturesque falls. You might want to cool off in the pool at the base of the falls, but your guide will tell you to beware of the lizard who supposedly inhabits this body of water. Legend has it that in order to go into the pool, you have to request permission of the creature. This is done by floating a ti leaf on the water. If the leaf floats, then the lizard will let you enter the pool, but if it sinks, the answer is no.

The Halawa Valley Cultural Tour is a highlight for most folks. You’ll meet father and son, Philipo and Greg Solatorio, who are actual residents of the valley. Philipo is the last Hawaiian elder living in this area. He was chosen at the age of five to be the family cultural practitioner, a responsibility he took seriously, spending his life listening and learning from others, eventually becoming a “kumu,” or teacher. Philipo’s successor, also selected at a young age, is his son, Greg, who recently returned to the valley to assume his duties.

Today, twelve people live in this remote locale, primarily off-the-grid. They practice their traditional ways in order to perpetuate their culture. “Culture is sacred, not secret,” says Greg. “We hope by offering these tours that we can help people experience our culture.” He adds, “Culture is meant to be learned from the inside out, not outside in. The best way to learn is to go to the source and experience the culture firsthand.” To enter the valley, visitors must ask permission.

Greg blows the conch shell, which is a means of communication and lets others in the area know there are visitors. Philipo, who is waiting at his house, makes a responding sound to acknowledge the message. Guests bring a gift of food (i.e. a coconut), which is placed at the altar near the home. There is chanting and a nose-to-nose greeting with an exchange of “ha,” or the breath of life. Greg explains that when you exchange the breath of life with someone, you become family and are no longer a visitor.

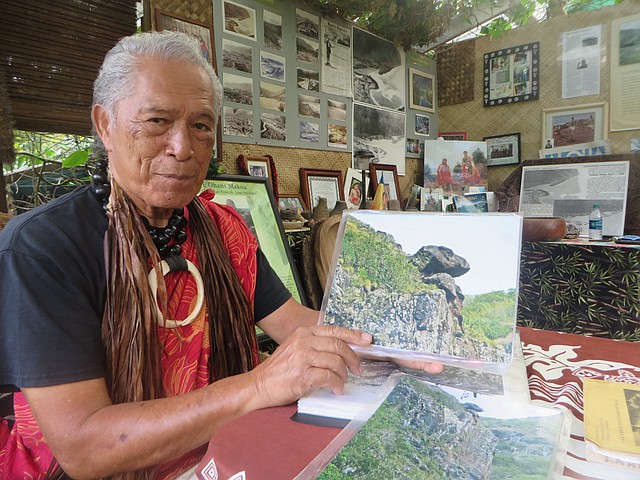

The Solatorios live off the land. They eat the wild pigs and deer, as well as the fruit and veggies they grow in their fields. Taro is an important crop to the family, as it was years ago. Greg notes that taro was the main staple of Hawaiians’ diet, as it was a superfood. Father and son wear traditional dress, which includes a kikeppa, or sarong tied at the shoulder. This signifies the role of a cultural practitioner. The colors – red, yellow and orange – are those belonging to the family, while the ti leaf worn serves as a spiritual protector. The pig’s tusk around the neck indicates location of one’s roots. Two teeth meet together in the piece, denoting that the Solatorios are from the Halawa Valley. And the kukui nut lei they wear represents enlightenment.

Visitors will see photos of family members and pictures of the valley as it was years ago with a school, church, post office and hundreds of taro patches. There were few trees and the river was much larger than it is now. Philipo was just a young boy when the first tsunami hit the valley in 1946. He describes the scene and the horrific noises he heard, becoming emotional in the process, as he shows before and after images of the area. The story is not one that many residents spoke about, so no one outside really knew what happened.

As we prepare to leave, Philipo thanks us for visiting and calls out, “A hui ho,” or “until we meet again.” I look back and see him returning to the task of weaving a basket of leaves. He smiles contentedly, as a halo of light from the sun illuminates his figure.

For more Hawaiian history, a trip to Kalaupapa National Historical Park is a must. Once a place of exile and despair, Kalaupapa today is a national historical monument. Surrounded mostly by ocean and cut off from the rest of the island by towering cliffs, the Kalaupapa Peninsula has always been one of the most remote places in Hawaii. It is for this reason the land was designated to be a settlement for the many Hawaiians afflicted with Hansen’s Disease or leprosy, back in the mid-1800s. It’s not known how leprosy came to the islands, but it appears in records as early as the 1830s. Hawaiians didn’t have any immunities to introduced diseases and thus were particularly vulnerable to infection. Hawaii’s ruler at the time, King Kamehameha V, in a desperate attempt to prevent the spread of the disease, signed an act authorizing forced isolation of those who showed symptoms. Beginning in 1865, police were required to arrest any persons suspected of having the sickness. Thousands of families were torn apart by the policy. Some fled or hid from authorities out of fear they would be taken away and never to be seen again. The shame associated with having a diseased family member caused others to even disown their sick relatives. Leprosy was viewed with horror and associated with disfigurement, rejection and expulsion from society. A diagnosis at that time amounted to a death sentence as there was no cure or affective treatment.

An estimated 8,000 individuals, ranging in age from four to 105, were sent to Kalaupapa over the years. The plight of those exiled drew the attention of various religious communities. The most famous of those who came to the settlement to help was Father Damien, who worked tirelessly to promote the dignity of those afflicted and improve their conditions. He and Mother Marianne Cope, Joseph Dutton and the Catholic Brothers and Sisters, along with many others, dedicated their lives to the people of Kalaupapa. Father Damien eventually contracted the disease and died at the settlement. Both Father Damien and Mother Marianne were later canonized and officially deemed saints by the Catholic Church.

Despite being separated from their families and sent away to a place they didn’t know, many of the residents at Kalaupapa went on to live remarkable lives, making notable contributions to society. With the advent of a cure in the 1940s, life at the settlement changed considerably and patients could hold jobs, attend events and take part in the various cultural and educational programs offered on site. They formed organizations like the Lions Club and scout troops for the kids, and celebrated holidays with parades and contests.

Although the state’s isolation policy was not officially abolished until 1969, forced isolation at Kalaupapa ended in 1949. Residents were free to leave and many did, going on to serve as international human rights advocates and goodwill ambassadors around the world. Some, however, chose to remain, as Kalaupapa had been their home for much of their lives. Today, there are fourteen former patients still residing on site.

To visit this fascinating place, you need to book a tour and either take a mule ride or hike down a steep, rugged 3.2- mile trail. As you descend from the towering cliffs, you will be treated to dramatic panoramas of the peninsula and Pacific Ocean. If you’re on one of Molokai’s famous mules, trust your animal’s surefootedness, especially when navigating the many (26!) precarious switchbacks on the narrow trail. These creatures know the way, though at times it may seem as if they’re heading awfully close to a precipice. Remember to lean back when going downhill and to do the reverse on the return, as it’s easier on these beasts of burden. Those who wish to eschew this adventurous journey, can opt to take a small charter airplane to the site and then join the mule riders and hikers for the tour.

Your escorted tour includes the Kalaupapa Settlement’s points of interest: the Bishop Home for Girls, the old hospital ruins, St. Francis Church, the bookstore, boat landing (barge service occurred only once a year from Honolulu), Mother Marianne Cope’s grave and monument, and houses for Park Service and State Department of Health employees, as well as for the remaining residents on site. You’ll also go over to the east side of the peninsula to see the original Kalawao Settlement area where male patients initially lived. There you can see St. Philomena Church and Cemetery, the site of the old Baldwin Home for the Boys and the remains of the U.S. Leprosy Investigation Station. From this side, the views of the coastline and valleys are magnificent and despite the difficult history of the place, it’s hard to ignore the beauty of the area.

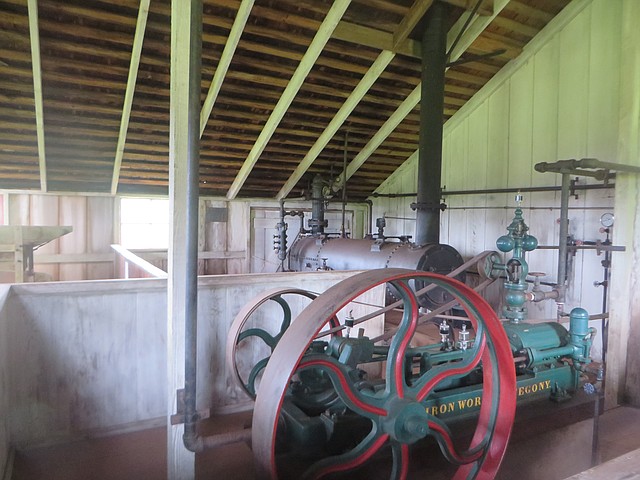

Other attractions to visit during your stay on Molokai include the restored R.W. Meyer Sugar Mill, Hawaii’s smallest mill, built in 1878 by German immigrant Rudolph Meyer; the adjacent Molokai Museum and Cultural Center with its historical exhibits and films; Kapuaiwa Coconut Grove, one of the few remaining royal coconut groves in Hawaii; Kaunakakai Wharf (a prime spot to watch the sunset); Purdy’s MacNut Farm for everything you want to know about growing, cracking and eating macadamia nuts; Big Wind Kite Factory, a colorful fixture in the west end village of Maunaloa where all the kites and windsocks are made by hand on site; and Papohaku Beach Park, a gorgeous stretch of white sand beach that you will most likely have all to yourself.

You’ll want to spend a bit of time in the town of Kaunakakai, the island’s main commercial hub, which is virtually unchanged since the early 1900s. Stop in at the Molokai Visitor Center for maps, suggestions and answers to all your questions. Then, check out the shops, grab any provisions you need at the grocery store and make a beeline for the Kamoi Snack-n-Go, where you’ll find Dave’s Hawaiian Ice Cream. With forty-eight delicious flavors, you’re guaranteed to find one (or several) you like, and the best part is you can sample as many as you desire, courtesy of the friendly gals behind the counter. Most popular is anything with coffee or macadamia nut, but the most requested flavor is Ube. I fell in love with this eye-catching purple-hued concoction at first lick. It’s made with purple yams, and it’s creamy, but not too sweet. Other unique flavors include Azuki Bean, Kulolo (Hawaiian taro pudding), Green Tea, Hau-olo (coconut with taro) and Chocolate Chip Mochi, just to name a few.

Kaunakakai is also home to Kanemitsu Bakery, where most nights, you can buy heavenly hot bread straight from the oven. To partake in this Molokai-only tradition, you’ll have to walk about fifty yards down a dark alleyway until you see a lit corridor, where there’s almost always a line. When it’s your turn, step up to the window and order one of the pillowy soft round loaves slathered with butter, cinnamon, cream cheese and/or jam. Eat it on the spot while it’s still warm. Top it off with a glazed taro doughnut for a real sugar buzz!

Another island tradition is sending coconut postcards to the folks back home. Stop in at the little Ho’olehua Post Office to “Post A Nut.” The postmaster has a selection of coconuts and markers to decorate and address them. Go all Rembrandt and be as artistic as you want! Cost is about $16 to mail to the mainland, depending on the size and weight of the coconut. Imagine your friends’ delight upon receiving this special Molokai memento!

For visitors interested in a volunteer experience during their stay, the Molokai Land Trust welcomes helping hands with a major dune restoration project at the Mokio Preserve. The private, nonprofit conservation organization is in the process of restoring the native ecosystem to an expansive area of land on the northwest coast of the island. Staff members will drive you out to the site, which is accessed only by four wheel drive vehicle, and you spend the day working side by side with them to remove invasive species, plant, collect seeds, do fence work, and other types of activities. “It’s a great way to interact with the community and the island, as well as connect with local Hawaiians,” says Butch Haase, Executive Director of the Molokai Land Trust. “We have visitors who return to help us each year when they come back to the island because they see that their work makes a significant difference.”

When it comes to accommodations, Hotel Molokai is the island’s sole active property, however, there are also some condo units and a few B&Bs, along with private beach houses and vacation rentals. I stayed at the hotel, which is located right on the beach and about two miles from Kaunakakai. Built in 1968, but since renovated, the place is “Hawaiian funky” in style and ambiance, with a unique charm of its own. The décor is Polynesian and each bungalow has its own private lanai and kitchenette. I kept my screens open each night so I could fall asleep to the sound of the waves and awake to the roosters announcing the day.

The hotel has a full service restaurant, where you can dine at the water’s edge. There’s also a lively bar that attracts visitors and locals alike. Folks gather poolside for happy hour and to enjoy the live entertainment. One night, it was a trio performing Hawaiian music; another, a group of schoolkids treated us to a show of traditional Hawaiian dances. It’s a friendly, convivial spot with a laid back vibe and true aloha spirit!

For all things Molokai: www.gohawaii.com/molokai

Debbie Stone is a travel and lifestyle writer, who explores the globe in search of unique destinations and experiences to share with her readers. She’s an avid adventurer who welcomes new opportunities to increase awareness and enthusiasm for travel and cross-cultural connections. Her stories appear in a number of print publications as well as on various travel-oriented websites. Debbie is a longtime Seattle area resident, who currently resides in Santa Fe, New Mexico.