The Fair that Put Seattle on the Map

September 5, 2012 at 11:58 a.m.

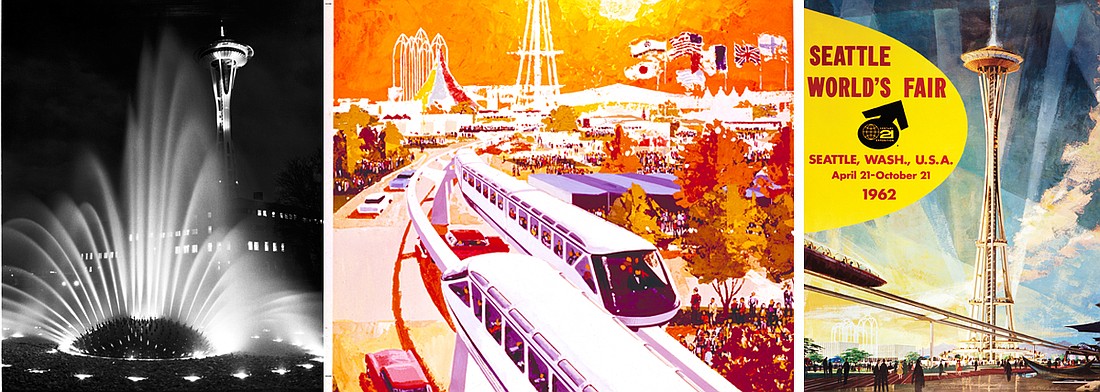

The Seattle World’s Fair (April 21-Oct 21, 1962), otherwise known as Century 21, gave visitors a glimpse of the future and left Seattle with a lasting legacy. The exposition gave Seattle world-wide recognition, effectively “putting it on the map.” Some of the many stars who gave performances in Seattle that summer included Sammy Davis, Jr., Louis Armstrong, Victor Borge, and Lawrence Welk. Among the well-known visitors were John Wayne, Jack Lemmon, Bobby Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Carl Reiner, Carol Channing, George Burns, Walt Disney, John Glenn, and Lassie. Elvis Presley came to town to make the film “It Happened at the World’s Fair” turning heads and causing girls to shriek everywhere he went. [excerpted from HistoryLink.com by Alan J. Stein]. The Seattle Center is celebrating the 50th anniversary with special events through October 21.

I am a rare breed. Not only was I born in Seattle, all four of my grandparents were firmly ensconced in the city I’m proud to call home.

I count myself lucky to belong to a rare cohort of original Seattleites who not only love their city, but are fortunate to possess a sense of place and belonging that goes back a generation or two, with familial memories that tap deep into the 20th century.

The spirit of hope and promise that defined the Seattle boom of the late 19th century was grandly and elegantly expressed in the Alaska Yukon Exposition of 1909. Here, the potential of the greatest gateway city north of San Francisco declared itself to the world. It’s not by accident that the tallest building west of the Mississippi – the Smith Tower – was a grand Beaux-Arts affair that reigned supreme in Seattle’s historic downtown core from 1914 until the arrival of a new kid on the block, almost 50 years later.

That new kid on the block was, of course, our beloved Space Needle, the shining, aspirational beacon of the Century 21 World’s Fair—a symbol of hope for a better tomorrow ingeniously and architecturally expressed as a sky dream anchored in solid Seattle earth.

To celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Seattle World’s Fair, on August 17th, I had the good fortune of inviting two Seattle native sons to speak to a group of residents and members of the public at a free event held in the Bistro of Chateau Bothell Landing across the street from the Northshore Senior Center in downtown Bothell. The headliners were Knute Berger and John Gordon Hill.

Knute Berger can be heard Friday mornings at 10am on KUOW (94.9 FM) as one of the roundtable news of the week pundits. He is the Mossback Columnist for Crosscut.com, Editor-at-Large for Seattle Magazine, and former Writer-in-Residence at the Space Needle.

John Gordon Hill is a local director and cinematographer most recently well known for putting together the Seattle World’s Fair documentary When Seattle Invented the Future that aired on PBS this spring. He has also produced hundreds of television commercials, TV episodes and documentaries on The Klondike Gold Rush and The Alaska Highway. He serves on the board at Cornish College of the Arts.

In addition to screening Hill’s documentary, Berger regaled us all with tales from the Fair and his new book, Space Needle: The Spirit of Seattle. Just listening to these bright, dedicated die-hard Seattleites exchange witty banter, swap stories and answer questions energized the room with fun and fascinating facts. The evening was spent with a couple of Seattle World’s Fair aficionados who know their stuff and kept the fortunate attendees curious and engaged.

Back to 1962: The architectural inspiration behind the tower help make it instantly recognizable around the world as “The Eiffel Tower of Seattle.” Visually Seattle is still punctuated by the slender, modern lines of a tower now recognized for her retro, period charm as much as her totemic universality.

In 1959, hotelier Eddie Carlson sketched an image on a coffee house placemat (or some say napkin) for what was to become Seattle’s defining symbol. Architect John Graham (of Northgate design-fame – the world’s first shopping mall) turned that original drawing into a “flying saucer.”

Berger tells us that UW architecture professor Victor Steinbruck was called upon to improve the rough sketch design for a revolving tower in the sky. He added the graceful upturned hands holding the flying saucer, giving a definitive feminine, curvy shape to the tower.

Take the Space Age exclamation point away from the north-end of the ever-growing sentence of city rooftops and the reader of Seattle’s urban landscape will be momentarily lost. The Space Needle has anchored and defined a city for 50 years, and she will continue to do so. Just as the Eiffel Tower is protected from encroaching obstructions of its timeless anchorage in Paris, so too does the Space Needle enjoy protected views.

Berger was fortunate to spend one year as Writer-in-Residence at the Space Needle while working on his new book, Space Needle: The Spirit of Seattle.

“When you get to go up into the Space Needle every day—to your own office on the Observation Deck no less—every day is different,” reflects Berger, somewhat wistfully. “That is what makes the Space Needle work. I got to write up there one day a week, and each week I’d see something new in the quality of the sky or the landscape below—or even in a subtle play of light.”

For Berger, the experience was almost “addictive,” and gave him a rich understanding of why The Space Needle is so effective. “It comes down to its height,” explains Berger. “While still taller than Queen Anne Hill, it is not too much taller.”

According to Berger, a group of original investors hired a helicopter to take them to the proposed height of The Space Needle. They started with the Eiffel Tower’s summit—1000 feet. It immediately felt wrong, so they lowered the chopper until they found a still breathtaking but Seattle-friendly equilibrium.

“The needle is at a perfect height of between 500 and 600 feet—idyllic, really for the scale and scope of Seattle,” confirms Berger. “Yet the structure is also fun and somewhat quirky, reflecting Seattle’s tremendous sense of humor. It’s high enough to enjoy breathtaking scenery of sky and sea, while still low enough to feel connected to Seattle.”

The Space Needle was a positive response to another structure going up halfway around the world—The Berlin Wall. “Where the Wall was closing people in, Seattle wanted a structure that would give the most expansive views possible,” Berger observes.

Expansive, visionary perspective on all levels is John Gordon Hill’s theory behind what made Century 21 click—on time, on budget and in perfect choreographed lock-step with the times. In his documentary, Hill lays out the personalities and civic pride that thrived in an era to make a perfect storm of World Exposition Success. The Seattle filmmaker has been a fan of the Fair since he attended as a kid, and when Channel 9 (KCTS) put out a request for proposals from filmmakers, Hill thought, “I could really do this—and I’d absolutely love to.”

His directional philosophy was unique from the get go. He didn’t want to be Seattle-centric in his approach to making the film. “Too often even well-produced local films have an insular quality that severely limits their audience,” observes Hill.

Rather, Hill wanted a film that would stand on its own two legs and play anywhere in the country. He didn’t come up with this idea in response to the prompting of an inflated ego, but rather because he firmly believes the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair was one of two events that truly defined Seattle.

The first, The Klondike Gold Rush, essentially financed the burgeoning growth of the new Northwest seaport. The 1909 Alaska Yukon Exposition qualifies as the first World’s Fair held in town, but it was essentially designed to celebrate the growth and success of the new city.

“In contrast,” declares Hill, “The 1962 World’s Fair was commemorating our shared human ambition for the Space Age of tomorrow, but it was also very deliberately designed to put Seattle on the map.”

In his film When Seattle Invented the Future, John Hill recounts the fascinating story of how the Century 21 planning group—men like Joe Gandy, Eddie Carlson, Ewen Dingwall and Al Rochester—believed in the future of Seattle with such passionate fervor that never before can a group of civic leaders be said to have had such a positive, lasting impact on essentially creating a world-class city—and all in a relatively compact amount of time.

“Ironically, there was no public process for the planning of this thing,” remarks Hill with a chuckle—“Something that would never fly in the Seattle of today.”

Rather, the ’62 World’s Fair was done for the highest and best of motives. The founders and planners believed in their city and were committed to a tremendous sense of civic duty, betterment for their neighbors and social uplift.

The World’s Fair was successful for all these reasons and more. The commitment of the founders, the civic pride and support of the city—these social factors combined with a collective sense of hope in the promise of American education, particularly in the field of science. Hill believes young scientists were more encouraged and fostered in mid-century America than they are today; empowered with the notion that science is something everyone can do.

“The belief in science that energized the social and cultural context going into the ’62 World’s Fair engendered a vote of optimism in otherwise frightening times,” reflects Hill. “Science was a way to leverage positive change, and the credo ‘If you can conceive of it, you can make it’ was championed by everyone in all strata of society—from politicians and leaders to teachers and in conversations over the family dinner table.”

When the World’s Fair opened in April 1962, the subtitle was Century 21: America’s Space Age World Fair. Ten million attended, and the Fair turned a profit—the only one of its era to do so. Of course, this being Seattle, the science and space pavilions might have had center stage, but a genuine desire for world understanding through peace, shared culture, international food and culture pavilions, and world class artistic performances marked the Fair for the truly memorable event that it was.

Performances by Shostakovich and others laid the groundwork for an arts hub that still thrives today. This evidence of foresight and deliberation stands firmly behind the reason over half a dozen theatres and performing spaces, including the homes for Seattle Opera, PNW Ballet, Intiman and Seattle Repertory occupy the former fairgrounds at Seattle Center.

In a final shout-out, without the ’62 World’s Fair, we would not have created the environment that fostered and encouraged Bill Gates, Paul Allen and Jeff Bezos who chose to draw on the promise of “the communications of tomorrow” touted at the Fair; to apply their mental genius to create, innovate and base their companies in Seattle.

So, too, did the dreams and promises of a World’s Fair, set on a relatively small uptown Seattle campus 50 years ago pave the way for the cutting edge Biotech and medical industries that define nearby Lake Union and save lives with the latest in innovative medical treatments and therapies. And beyond a doubt, the fact that The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is Seattle Center’s newest neighbor is a credit to a vision that became a reality.

World’s Fair and its Legacy

The Next Fifty, now through Oct. 21at the Seattle Center, commemorates the 50th anniversary of the 1962 World’s Fair with an array of events and activities. For more information, visit http://www.seattlec…">www.seattlecenter.c… or call 206-684-7200.

So what about the next 50 years? The dreams, visions, hopes and aspirations of yesterday and today will continue to become reality, making the world a better place of peace and understanding, just as was intended when President John F. Kennedy opened the Fair via satellite telegraph key on April 21, 1962.

John Gordon Hill’s documentary, When Seattle Invented the Future, is available from KCTS (www.channel9store.com) or from Amazon.com. Space Needle: Spirit of Seattle, by Knute Berger, is available online, at bookstores, and with a hardbound copy available at www.channel9store.com.

This article appeared in the September 2012 issue of Northwest Prime Time, the Puget Sound region’s monthly publication celebrating life after 50.