This month marks the 53rd anniversary of America’s only unsolved skyjacking: the D.B. Cooper saga. As of July 2016, the FBI’s website refers to the case as one of the longest and most exhaustive investigations in the Bureau’s history, but that resources were redirected away from the case at that point. Will new reporting now cause the FBI to reopen the investigation?

The FBI website specifically claims that “should specific physical evidence emerge–related specifically to the parachutes or the money taken by the hijacker–individuals with those materials are asked to contact their local FBI field office.” Media outlets around the world are reporting that such evidence has been brought forward by the children of the leading suspect.

First read an account of the original skyjacking by the suspect known as D.B. Cooper, then keep scrolling to read the updated news.

The following essay by Katherine Beck is courtesy of HistoryLink.org, the free online encyclopedia of Washington state history

Dan Cooper (aka D.B. Cooper) parachutes from skyjacked jetliner on November 24, 1971

On the dark and stormy Thanksgiving Eve of November 24, 1971, a skyjacker calling himself “Dan Cooper” commandeers a Northwest Orient Airlines 727 shortly after it takes off from Portland, Oregon, for Seattle. After collecting a ransom of $200,000 and four parachutes in Seattle, the skyjacker (erroneously dubbed “D. B. Cooper” due to a misunderstanding by a reporter during a press briefing) directs the crew to fly to Mexico. Somewhere over southwest Washington, while the crew is in the cockpit, he lowers the plane’s tail stairway and vanishes into the rainy night. Fragments of the ransom money will be found on a Columbia River bank in 1980, and multiple theories about his identity will abound. But no one will be able to figure out for sure who Dan Cooper was, or if he dies that night or lives to profit from his crime. The FBI redirected resources away from the case in 2016. (Read the FBI’s account at the following link: https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/db-cooper-hijacking)

“Miss, I Have A Bomb Here…”

The passenger who gave his name as Dan Cooper was about six feet tall and 175 pounds with brown eyes, wavy black hair, a receding hairline, and an olive complexion. He appeared to be in his late 40s. He boarded the airplane wearing a dark suit with a black tie, loafers and a black raincoat. He carried an attaché case. He had bought a $20 ticket at the last minute, after first confirming that the aircraft was a Boeing 727, a model equipped with an aft staircase.

Once aboard, he took a seat in row 18, the last row, ordered a bourbon with, depending on the source, either Seven-Up or water, and passed a note in an envelope to stewardess (as flight attendants were then called) Florence Schaffner. Used to getting notes from flirtatious male passengers, she accepted the envelope but ignored it and put it in her purse unread. The passenger told her he thought she’d better read it. She did. It said, “Miss, I have a bomb here and I would like you to sit by me” (Gray).

“Are You Kidding?”

When she asked him if he was kidding, he opened the attaché case to reveal what looked like red sticks of dynamite, a battery, and some copper wire.

The hijacker said that when the plane landed in Seattle, he wanted $200,000 in cash, two back parachutes, and two front or reserve parachutes designed to clip to the main parachutes. He also said he wanted a refueling truck standing by on the tarmac, and he asked for meals for the flight crew. He ended his demands with the threat “No funny stuff, or I’ll do the job” (Gray).

The request for two parachutes indicated that the hijacker might be planning to force a hostage, possibly a stewardess, to jump with him. That threat would ensure that any parachutes provided would have to be in working order. The threat of a bomb, rather than the usual gun that hijackers were then wielding (there had been a more than 100 skyjackings since 1968.) was also ominous. The implication was that the hijacker was desperate enough to commit suicide.

Schaffner took the demands to the cockpit, while stewardess Tina Mucklow replaced her in the seat next to Cooper. He wanted a stewardess next to him. She accepted one of the Raleigh cigarettes he was smoking. He asked her where she was from and told her that her home state, Minnesota, was a nice place. At one point, he looked out the window and noted that they were over Tacoma, revealing a familiarity with the area. Mucklow asked him if he had a grudge against Northwest Orient, an airline that had been beset with strikes and labor troubles. He told her, “I don’t have a grudge against your airline, Miss. I just have a grudge” (Gray).

Meanwhile, Down on the Ground…

The other 36 passengers were unaware that the plane had been hijacked, but on the ground, authorities were scrambling. (Later into the flight, at least one passenger suspected that something was amiss.) The CEO of the airline in Minnesota decided that the airline, which was insured against such an event, would pay the ransom. A Seattle police detective went to the downtown office of the Seattle First National Bank and collected a canvas bag with $200,000 in twenty-dollar bills. The non-sequential serial numbers had been recorded on microfiche, part of a routine process the bank had in place to foil a potential robbery. The detective headed off with the ransom to Seattle’s Sea-Tac International Airport.

Meanwhile, a cab delivered two parachutes provided by a local parachute rigger to the airport. State troopers went to Issaquah Skyport, a parachute jump center in a nearby town, sirens blaring, and picked up two backup front parachutes. In the scramble, the jump center inadvertently supplied one dummy parachute that couldn’t open. Crew meals and parachute instructions were also included in the collection of items ready for the final descent of flight 305, which was now circling Seattle in a thunder and lightning storm. Passengers eager to get to their Thanksgiving destinations (dinner the next day) were told there was a mechanical problem requiring that the pilot burn off some fuel.

After the half hour flight from Portland and three hours in the air circling Seattle, the plane landed. Outside, snipers were lined up and authorities tried to stall the hijacker by claiming it was too cold to refuel. An impatient Cooper used the cabin phone to the cockpit to demand that they “get this show on the road” (Gray).

While passengers were still aboard, Cooper went into the lavatory with his attaché case and emerged with the case and an additional bag, which presumably had come from inside the case. Mucklow was told to leave the plane and return with the canvas bag full of money, which she duly did. Only then were passengers allowed to leave. Slight panic ensued when one of them reboarded the plane to retrieve something he had left behind.

Your Instructions Are…

Cooper gave instructions to Mucklow, which she relayed to the cabin. They were going to Mexico City. They must fly with the landing gear down and the flaps at 15 degrees. They must not fly higher than 10,000 feet, an altitude at which the cabin would not be pressurized, ensuring that the hijacker would not be sucked out into the night if the rear door was opened in flight.

He also wanted the plane to take off and fly with the aft stairs down. No one at Northwest knew if this was possible. The crew was told what engineers at the nearby Boeing Company, where the plane was designed, built and certified, had to say. The engineers told the airline that the plane couldn’t take off with the aft stairs down. And they also provided information that no one else in civil aviation circles knew, but what some have speculated that perhaps the hijacker did know. The 727 had successfully flown with the aft stairs down. This had taken place in secret missions run by CIA front airline, Air America. More than 300 pounds of supplies at a time, as well as agents, had been dropped from the aft stairs of an airborne 727 behind enemy lines in Vietnam.

The crew was able to talk to the ground without the hijacker listening. At least one nearby commercial flight in the vicinity broadcast the air-to-ground communication into the cabin for the entertainment of the passengers.

The crew also needed to figure out where to refuel. At the speeds the hijacker had demanded, they’d have to do it twice on their way to Mexico City. They decided on Reno, Nevada, and Yuma, Arizona. The hijacker approved this flight plan, but when they told him they needed time to file the flight plan he told them to do it later, over the radio. He was becoming impatient.

Cooper insisted that the pilot, co-pilot, and engineer come no farther than the first-class curtain. Throughout the entire flight they remained in the cockpit and never saw Cooper. Once the plane had landed in Seattle, they could have escaped from the cockpit on a rope ladder, but refused to do so because stewardess Tina Mucklow was still on the plane in the cabin with the hijacker.

Merchandise Not as Ordered

The hijacker was upset that the cash hadn’t come in a knapsack as requested, but in the canvas bag from the bank. Despite his irritation, he offered Mucklow a stack of the bills, which she refused, on the presumably joking grounds there was no tipping allowed. After the passengers deplaned, Cooper allowed the two other stewardesses to get past him to retrieve their purses before they left the plane. He tried unsuccessfully to tip them, too, with the cash in his pockets, change from the drink he’d purchased. They too refused a gratuity.

Now alone in the cabin with Mucklow, Cooper addressed the problem presented by the fact that he hadn’t received the knapsack he’d asked for. Backpacks were not a common item in 1971. He improvised by opening one of the reserve chutes, the one that wasn’t a dummy, and, using a pocketknife he’d brought along, cut lines from the chute, secured them to the bag of cash, and fashioned a handle for it.

He told Mucklow he’d need her to lower the aft stairs for him. She was worried she’d be sucked out of the plane and asked that she be allowed to be tied to something with more of the rope from the parachute. The hijacker said “Never mind,” (Gray) and asked her to show him how to lower the stairs himself.

Last Minute Details

She showed him how it worked and also explained that there was oxygen on board should he need it. He said he already knew its location. Dan Cooper clearly knew his way around the cabin of the 727, as well as knowing how the plane should be flown to accommodate a jump.

In response to her query about the bomb, he said he’d take the bomb with him or disarm it. The pilot had already been told from the ground that an FBI expert expected him to blow up the plane and the crew after he jumped. (Later, when it was learned that the sticks of “dynamite” viewed by stewardess Florence Shaffner were wrapped in red paper, it was thought that they were probably harmless highway flares, since real dynamite was wrapped in tan paper.)

Cooper then directed Mucklow to go to the cockpit and on her way there to pull the curtain between first class and economy behind her. As she turned to do so, she saw him tying the sack with the money around his waist. That moment was the last time another human being knowingly had visual contact with Dan Cooper.

The Flight to Nowhere

The plane took off, with Mucklow and the other three crew members in the locked cockpit. But flight 305 was not alone. Two F106 fighters from McChord Air Force Base were scrambled to follow the plane. But it was tough for the supersonic aircraft to follow a plane going at such low speed. In addition, two Idaho Air National Guard F102 aircraft were dispatched from Boise, Idaho. A nearby Air National Guard flight instructor on a night training mission in a T-33 reconnaissance aircraft was also called into action.

Farther to the south, Portland-based FBI special agent Ralph Himmelsbach, a fixed-wing pilot himself, along with a fellow FBI agent and two members of the Oregon National Guard, were taking to the air in a Huey helicopter. Himmelsbach had been on the case since hours before when the pilot had radioed shortly out of Portland that there was a hijacking underway.

Five minutes out of Seattle, at 7:42 p.m., a light went on in the cockpit. It was the aftstair light, which meant that Cooper had managed to get the stairs down. The co-captain called back into the cabin. Dan Cooper picked up the phone. He was appeared completely familiar with the intercom system on the plane. When he was asked if he needed help, he answered with one word. “No.” It was now 8:05. Later, the co-pilot again used to intercom to ask if everything was okay. Dan Cooper picked up and said it was.

No one has knowingly heard from Dan Cooper since.

A Leap Into the Dark

It was minus seven degrees Celsius outside the plane, it was dark, and there was sleet and hail. At one point, the crew felt oscillations in the cabin. Later tests with a 727 and a weight about the weight of the hijacker and the money — another 21 pounds — produced similar oscillations, and indicate that when these oscillations were felt was when the hijacker leapt into the dark.

After the oscillations, the crew got back on the intercom to see how things were going. They addressed the hijacker as “Sir,” just as he had addressed the stewardesses as “Miss.” This time, there was no response. FBI agent Himmelsbach later figured that after struggling with the aft stairs, the hijacker clung to them for about two minutes before disappearing into the night.

Later the 727 landed in Reno with the stairs down, creating runway sparks. The crew unlocked the cockpit door. The captain crept into the passenger area. There was no one on the plane, but two chutes remained. One was the reserve parachute that had been cut up to attach the cash bag to the hijacker. The other was the most efficient back parachute. The hijacker had chosen instead an ex-military parachute that was harder to control. The other reserve front chute, was one that was actually a dummy, but it couldn’t have been attached to the military chute the hijacker chose anyway.

Left-handed Smoker with Cheap Tie

The plane was thoroughly searched and fingerprints were lifted from every surface the hijacker touched. The hijacker had also left behind his polyester tie, a $1.50 clip-on from JC Penney with a cheap imitation pearl tie pin, which appears to have been attached to the tie by a left handed person. In subsequent years some DNA from three people has been retrieved from the tie, which, in the decades between the hijacking and the development of DNA forensics, had probably been carelessly handled. The tie also produced some pollen from a common garden plant, impatiens.

The hijacker’s Raleigh cigarette butts, a bargain brand which the hijacker must have smoked a lot of over the years (his fingers were nicotine stained), were also taken from the scene. The cigarette butts, which might have provided more accurate DNA samples than were found on the tie, have apparently been lost over the years. Agents also recovered a hair from the headrest and another from the arm rest.

In the days and weeks to come, massive searches were conducted over the area where the hijacker was thought to have landed, near the small town of Ariel, Washington. Nothing was found.

Forty years on, Ariel continues its annual celebration of D. B. Cooper’s historic caper. He soon took on the status of a Robin Hood-like folk hero. Tee-shirts were silk screened and ballads were written to commemorate his feat.

Did Dan Cooper Die?

The FBI has generally maintained that his jump into the freezing sleet over a thickly wooded area was fatal. He wore no protective clothing, choosing instead, the kind of business attire — suit, raincoat, dress shoes — that male passengers usually wore on airplanes in 1971. A parka and boots, normal traveling attire today, might have attracted attention.

And the fact that he didn’t request protective clothing or a helmet, that he chose to bail out with the less effective parachute, and that he didn’t spot the dummy chute and cannibalized instead the only working backup parachute, indicated to the FBI that although he might have known his way around a 727, he wasn’t an experienced parachutist.

Hints, Finds, Afterthoughts

In November, 1978, a plastic placard with operating instructions for the aft stairs, was found by a hunter 13 miles west of Castle Rock, Washington, in the 727’s flight path. Boeing engineers who had inspected the hijacked plane after the event had noticed it was missing. It was presumed to have been torn off by the wind.

A more spectacular find occurred in February 1980 along the banks of the Columbia River, nine miles downstream from Vancouver, Washington. Three bundles of the marked twenties that were part of the ransom were found buried in the sand by an 8-year-old boy. The recovered cash was degraded and experts said it could have been washed into the Columbia from another location and perhaps also been moved by dredging operations. One hundred and ninety thousand dollars of the ransom remains unaccounted for. Despite the offer of rewards for the marked bills, none have ever surfaced.

According to Ralph Himmelsbach, because the cash was found five miles above the confluence of the Lewis River watershed and the Columbia River, the actual drop area must have been not around Ariel, Washington, in the Lewis River watershed as originally supposed, but over the next ridge, in the Washougal River watershed. Himmelbach believes that the error was made because the original calculations didn’t take into account strong crosswinds he later learned about from a pilot who had been flying in the area that night.

Himmelsbach also believes that Dan Cooper died on that Thanksgiving Eve of 1971.

Claimants But No Suspects

Others however, have proposed numerous suspects over the years. They include a former Green Beret who was convicted of a similar hijacking, an ex-con whose wife claims he made a deathbed confession, a former Northwest Orient steward who seems to have come into some money soon after the hijacking, an amateur pilot, who after a transgender operation, claimed, as a woman, that as a man she was D. B. Cooper, and an Oregon surveyor whose niece says he showed up late for the family Thanksgiving dinner in 1971 bloody and bruised and gloating about his success. All are deceased and none have been linked to the crime by forensic evidence.

Tina Mucklow, who spent five hours with Dan Cooper, more than anyone else, was by all accounts an excellent witness and a conscientious crewmember who handled herself bravely and calmly during the ordeal. After retrieving the bag of cash on the ground in Seattle, she apparently did not hesitate to re-enter the airplane despite the risks of being blown up or forced to make a possibly lethal parachute jump so that her passengers could be freed.

In the 40 years since the hijacking, Tina Mucklow has declined to give interviews about her experience, saying that she doesn’t want to imperil airline safety by making a hero of Dan Cooper. She also said, “He was never cruel or nasty in any way” (Gray). Mucklow later became a nun.

Case Not Closed (2016 update… FBI reports that resources have been allocated away from this case)

Agent Ralph Himmelsbach, who in 1986 self-published a book about the case, points out that Dan Cooper jeopardized the lives of passengers and crew and has characterized Dan Cooper as “a rotten, sleazy bastard” (Gray).

The FBI kept the case open for more than 50 years. An agent in Seattle was assigned to the case and followed new leads until the FBI reallocated resources away from the case in 2016. If the man who checked in to flight 305 as Dan Cooper is alive today, he would be in his 90s.

KEEP SCROLLING TO VIEW UPDATED REPORTING (below “Sources”):

Sources: Richard Seven, “D. B. Cooper, Profile of a Suspect,” The Seattle Times, November 17, 1996; Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 1, 2000; Casey McNerthney, “FBI Says No DNA Match in D.B. Cooper Case,” SeattlePI.com, August 9, 2011; Geoffrey Gray, Skyjack: The Hunt for D. B. Cooper (New York: Crown Publishers, 2011); Skipp Porteous, Robert Blevins and Geoff Nelder, Into The Blast: The True Story of D.B. Cooper, Revised Edition (Kindle Edition, January 6, 2011); Ralph P.Himmelsbach and Thomas K. Worcester, NORJAK: The Investigation of D. B. Cooper (West Linn, Oregon: Norjak Project, 1986.)

NEW:

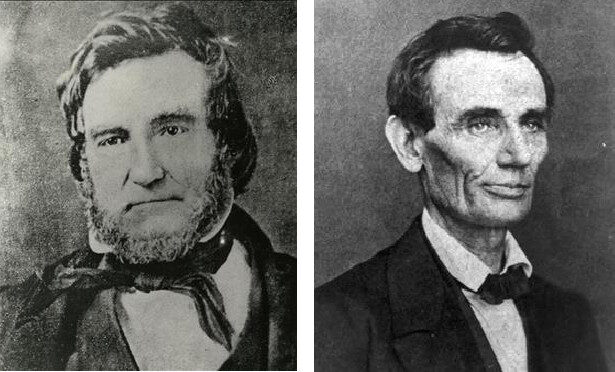

Richard McCoy Jr was a serious suspect during the FBI’s investigation of the D.B. Cooper case. The following year, McCoy was arrested and convicted for a nearly identical skyjacking in April 1972 from a flight out of Denver, Colorado. Two years later, after escaping from prison, McCoy was killed in a shootout with FBI agents. However, McCoy was never charged with the infamous D.B. Cooper skyjacking. According to Cowboy State Daily, McCoy’s children, Chanté and Richard III (“Rick”) long believed their father to be D.B. Cooper. However, all in the family stayed quiet for fear their mother would be implicated as being complicit in the crime. Their mother has since died, and the children of McCoy have turned over a harness and parachute they believe to have been used in the D.B. Cooper skyjacking.

According to reporting by several news outlets, the FBI informed the McCoy family that their father’s body may be exhumed as part of a reopened investigation, but no updates have been reported by the FBI as of November 26, 2024. The FBI will not confirm or deny that it is actively re-investigating the case.

MORE INFORMATION

- You can read a detailed account of the updated efforts involving Richard McCoy Jr at the following link: Who is D.B. Cooper? New Evidence May Crack One of America’s Greatest Mysteries

- Check out the annual D.B. Cooper Conference, which this year took place from November 15-17 at Seattle’s Museum of Flight: The 2024 DB Cooper Conference

- Netflix produced a documentary entitled “D.B. Cooper, Where Are You?” D.B. Cooper: Where Are You?! | Netflix Official Site