Imprisoned!

April 10, 2012 at 10:24 a.m.

On March 12, 1942, headlines in Seattle’s North American Times read: EVACUATION OF JAPANESE DUE WITHIN 10 DAYS.

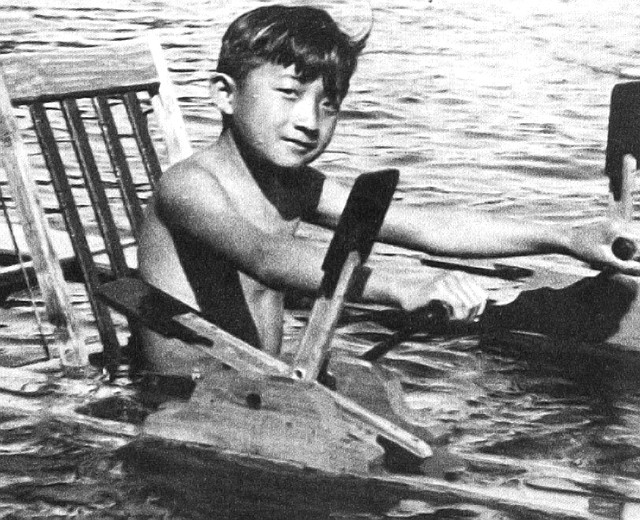

For 13-year-old Yukio Tazuma, evacuation from his home in Seattle to Camp Harmony at the Puyallup Fairgrounds, was an adventure.

“I guess I was very tolerant (and ignorant) thinking this was like going out on a long camping trip…no school, playing pinochle and ping pong all day!” recalls Yukio.

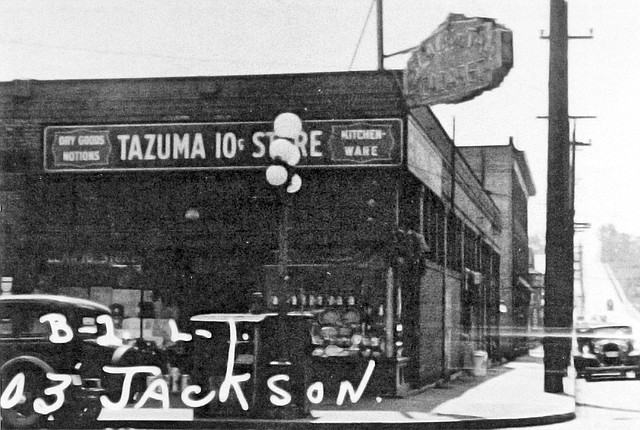

However, Yukio remembers his dad and oldest brother, Elmer, discussing at breakfast, what to do with their dime store. Have a 50 percent discount sale? Pack all merchandise into storage for how long, at what cost? Move the merchandise to a new store some place inland at the risk of encountering racial violence, injury? Sell the store at any price?

“My conservative dad chose the last idea and got 10 percent of the store’s value.”

Yukio and his family joined 7000 other Japanese-American families that day.

“My folks, three brothers and I carried one suitcase each,” says Yukio.

The family walked two blocks from their Seattle rental house on 12th Avenue South. Bags were loaded onto trucks while inmates boarded buses and escorted by the military to the Puyallup Fairgrounds.

“We were enclosed within a barbed wire fence with armed sentry guards along the fence perimeter preventing our escape,” says Yukio.

His family was assigned to one room within a barrack; they ate in a large mess hall, used communal toilets and wash rooms, and crossed muddy fields to get from barrack to barrack.

Yukio notes, “Impossible to walk on without boots! - - But who came prepared with boots?”

He adds, “Two months later, we were herded onto trains headed to the Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho.”

Prompted by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, ordering the internment of all Japanese Americans. Approximately 120,000 people would be imprisoned in camps mostly in the west - California, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Idaho, and also Arkansas. Ten thousand people were housed at Camp Minidoka in Hunt, Idaho.

Yukio says of his Minidoka adventure, “In my youthful, naïve optimism, I was still able to maintain a positive, adventurous outlook on our new life in Idaho.”

The sand blew in the strong winds, covering everything and everyone.

“So what...just cover your face and run for cover!” says Yukio, adding, “If you’re young and irresponsible, this was sort of a new fun.”

During stifling hot summers, “We had fun swimming every day in the man-made canal, which ran adjacent to the camp. After a drowning accident, two swimming holes were dug, and euphemistically called pools. They were just mud holes, and after one filthy use, we happily returned to the clean water of the canal.”

In freezing cold winters, “We had fun ice skating every day on the now frozen canal. It was free and within walking distance.”

He added, “One time, I went skating late in the evening so that I would have the ice entirely to myself.”

Yukio wanted to skate on the clear ice in the middle of the canal and fell through.

He says, “Swimming was my first love over other sports like baseball, basketball, and football. Because of my self-confidence in water, I knew I would be buoyant, extending my arms above the ice and slowly wading with the current over each new breaking ice.”

He admits he was never concerned with his safety.

“My only concern was the ridicule I would have suffered if my friends were here to witness my recklessness.”

All adult inmates were expected to occupy themselves and help sustain the operation of the camp.

Yukio says, “My dad began as a manual laborer. Later, when co-operative stores were established to sell general goods to the inmates, Dad as a former retailer, was elected co-op manager at $19 per month.”

His mom worked in the kitchen and Yukio became a garbage collector.

During his confinement, what started out as adventure and fun, turned into disillusionment and hard times entering his third year at camp.

Two good friends from Seattle’s Bailey Gatzert Elementary School, Toki and Jack were also interned at Minidoka.

Yukio says, “Strictly by chance, we were confined to the same Block 28.”

By now, the three friends were taught American History in their barrack school.

“Miss Batchelder was a white-haired, New Englander, who was teaching us the meaning of America,” says Yukio.

At 16, the three boys were frustrated over the internment and became rebellious.

Yukio recalls Miss Batchelder entering the classroom and not getting the respect and quiet she needed, said, “You people don’t appreciate the education you’re getting. I have nephews sacrificing their lives. They’re fighting in this war for all of you.”

More Information

*Tour the 1910 Panama Hotel in the International District to see a collection of photos, artifacts and newspapers of 1942 and to visit the hotel’s original bathhouse, the only remaining, intact Japanese bathhouse in the United States. The hotel has received National Historic Landmark status. The Panama Hotel: 605 ½ S. Main Street in Seattle, 206 223-9242, Jan Johnson, Owner.

*Visit the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial. The memorial pays tribute to the 277 people who were removed from their Bainbridge homes in 1942 and corralled at the Eagledale Ferry dock. The memorial was dedicated on August 6, 2011. Located at Pritchard Park, 4192 Eagle Harbor Dr., Bainbridge Island, 206 842-2773, info@bainbridgehist…

*Consider reading two award-winning Northwest-based novels that explore the impact of the Japanese-American internment: Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet by Jamie Ford; and Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson

*Bitter and Sweet Tour – Based on the NY Times bestselling book Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, visit the neighborhood and stops the characters frequented. Perfect for book clubs! 206-623-5124 ext 133, http://seattlechina…">seattlechinatowntou…

With anger building, harsh words directed at their teacher erupted from the two buddies, then from Yuki. All three had brothers who were also fighting for America in the war.

Yukio yelled, “My brother’s in the army.”

At which point teacher Batchelder shouted at the boys, “GET OUT!”

Yukio, once a naïve, happy-go-lucky 13-year-old boy enjoying a new adventure “off to camp,” became frustrated with the unfair, unjust situation that the grown-ups had already known.

The Aftermath

In 1946, the last camp closed. Inmates left with fare for transportation plus $25 per person.

Yukio puts it, “As Ed Murrow might have said Goodbye and Good Luck!”

Yukio’s parents returned to Seattle and started over as cooks at the New World Café. They subsequently managed the Benson Hotel.

President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act in 1988 apologizing for the internment and granting $20,000 to each Japanese American imprisoned during the war. Yukio’s 90-year-old mother had died in 1986. His Dad died at 104 years old in 1988. Neither saw any of that money.

Yukio attended The Institute of Design in Chicago. He later transferred to the University of Washington where he received a BA degree in Industrial Design. A long-time Boeing employee, Yukio married and has a son. He lives in Renton, Washington.

This article appeared in the April 2012 issue of Northwest Prime Time, the Puget Sound region’s monthly publication celebrating life after 50.