Egan on Curtis

March 25, 2013 at 1:12 p.m. | Updated March 11, 2013 at 4:50 p.m.

A third-generation Westerner, Timothy Egan is a true Washingtonian—born in Seattle, raised in Spokane, and living in Seattle once again.

This Pulitzer Prize winning reporter is a New York Times opinion columnist and critically acclaimed author of seven books including his National Book Award winner The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl. A graduate of the University of Washington and father of two (Sophie and Casey), Mr. Egan lives in Seattle with his wife, journalist Joni Balter of Seattle Times fame.

Egan comes from a family of nine, “from a mother who loved books and a father with the Irish gift of finding joy in small things,” (from timothyeganbooks. com). In an interview with High Country News (9/14/09, Moir) Egan said, “My mother loved the outdoors. When I was a kid, we'd go on walks where she would sing the praises of nature. She was the best proselytizer for the Northwest. Although she wanted me to travel and to see the world, she said… ‘you'll see there is no better place than here.’ ” Love of the Northwest followed Egan into his professional life and he became a consummate writer of the Northwest landscape. His breakout book, The Good Rain, is consistently voted one of the ten essential books about the Northwest environment. And his mother was right; he did see the world. “During my years working as a national correspondent for the New York Times, I traveled nearly 50,000 miles a year – all over the West.”

From a self-described blue-collar background, Egan worked on a farm bucking hay, in a factory, and at a fast-food restaurant “while muddling through nearly seven on-and-off years of college.” He also worked at the high school and college papers and jump-started his writing career covering the grounding of the Exxon Valdez as a stringer for the New York Times.

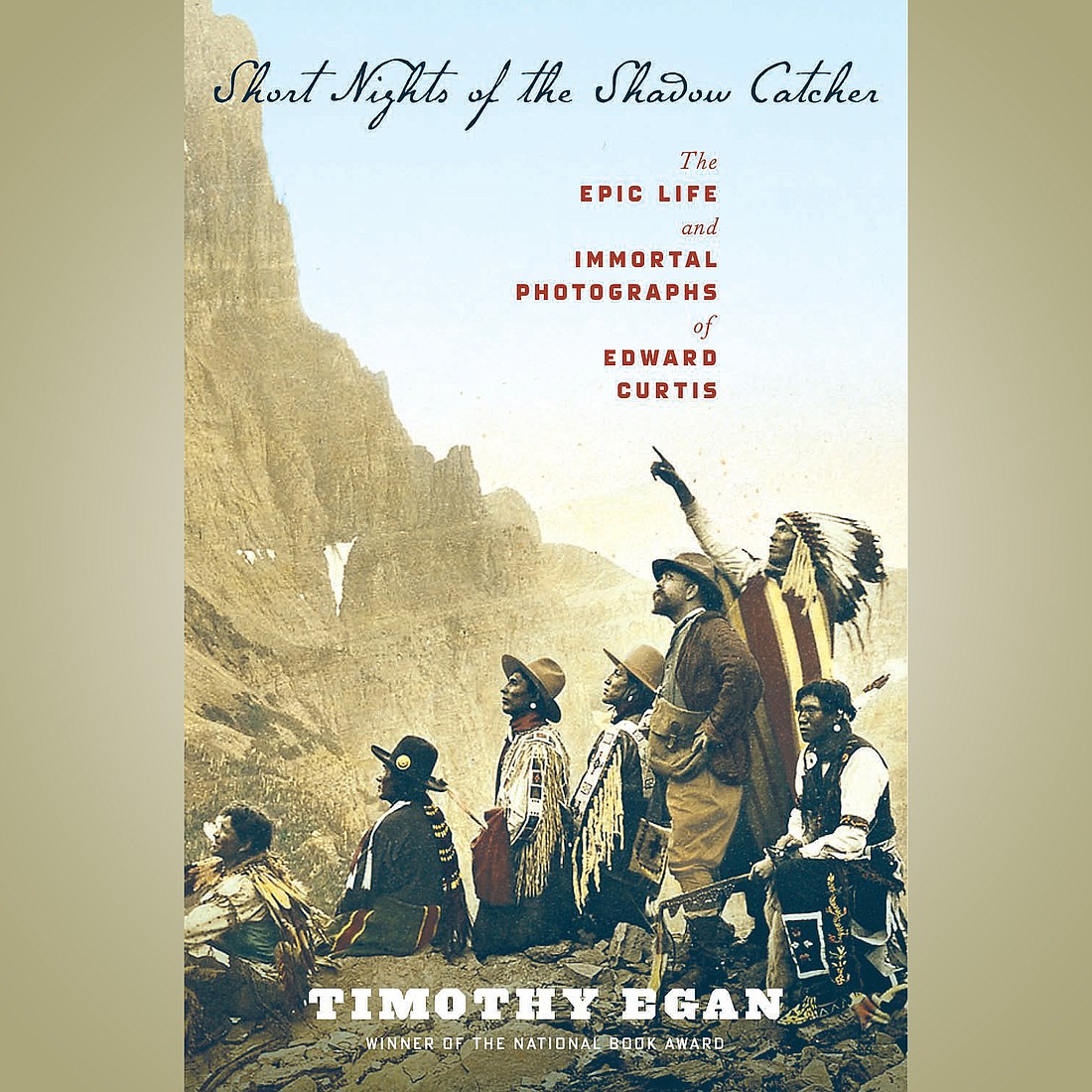

His most recent book is Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis. Egan contends that Curtis created one the greatest – if not the greatest – photographic and artistic epics of our times. “Perhaps the greatest anthropological excursion ever undertaken by a single human being,” said Egan in an interview on Well Read, a local public television program featuring books and writers. “Curtis’ work, the twenty volumes that make The North American Indian, is an American masterpiece, what has been called the greatest change in the book since the King James Bible.”

Egan describes Curtis as a superstar of his time, movie-star handsome, the most famous Pacific Northwesterner for much of the 20th century. “And yet,” said Egan, “we have sort of forgotten about him. I am trying to resurrect Curtis…to resurrect the scope of what he pulled off—a lone man, son of a preacher, sixth grade education.”

Curtis’ epic undertaking starts with Chief Seattle’s daughter Angeline. She was living in Seattle—a city named after her father that had outlawed Indians. He stumbles upon her and wants to take her photo. That was the start of his epic, reports Egan. “His studio photography that had made him famous gave way to his big, magnificent obsession.” Egan said that the experience of handling Curtis’ original books…“gave me the shivers. The pictures are luminescent.” Egan describes how Curtis carried around heavy and dangerous glass plate negatives throughout his journeys—whether mountainsides or wild, untamed rivers. “To turn the pages of these things and see these original Curtis [photos] are just chilling,” said Egan.

A review of Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis follows.

Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher

…review by David Holahan

Edward Curtis led a life that would make for implausible fiction. He parlayed a sixth grade education, a hardscrabble childhood, and boundless ambition into fame and quasi-destitution, simultaneously. At the peak of his success – as he supped with President Teddy Roosevelt and photographed his children, played Carnegie Hall, and convinced J.P. Morgan to be his patron – Curtis was living hand-to-mouth. The banker would pay for some of his expenses, but not a penny in salary. And virtually every cent of his and Morgan’s went to The Cause: documenting – celebrating is probably a better word – the lives and cultures of Native Americans. He accomplished this not simply with his evocative photographs. He also did it in compelling prose, through audio recordings of fading languages, and by using a new medium: moving pictures. These were not potshots. Curtis had to gain the trust of his subjects, who, unsurprisingly, were exceedingly wary of white people in the early years of the 20th century.

Curtis lived with and often like the people he captured on film. He was at home in the wilderness, could travel great distances and endure frequent privations. He dodged eternity now and again, often with his children in tow. In a Hopi snake ceremony, a hissing rattler was gingerly draped about his shoulders. Curtis saw himself in a mad race to photograph the First Americans before the American Century crushed their spirit and steamrolled their traditional ways. In the argot of the era, as well as in the caption of one of Curtis’ most famous photographs, Indians were a “Vanishing Race,” drowning in the melting pot. Indeed, such was the intent of the federal government, which criminalized Native religious ceremonies and sought to separate Indians from their culture and communal lands. Often, both Curtis and his photographic subjects were breaking the law.

Timothy Egan seems to have gone to school on his subject to write Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis. The ungainly title of his seventh book notwithstanding, the author artfully frames a stunning portrait of Edward Curtis that captures every patina of his glory, brilliance, and pathos.

Curtis’ greatest legacy is his 20-volume opus titled The North American Indian, which depicts dozens of Indian tribes from Oklahoma to the Pacific coast, from the Great Plains to remote Alaskan islands where bureaucrats and missionaries dared not tread. This Herculean task consumed Curtis for more than three decades. It also divided his family, destroyed his marriage, dissolved friendships, degraded his health, and left him without ownership of his own photographs.

The gain for all that pain, however, was truly remarkable. Using his camera, he painted a vivid and romantic portrait of the former masters of a continent as no mere ethnographer, academic, or Hollywood director ever could. Each photograph is a mini volume unto itself: artful, arresting, and the embodiment of a larger story. Academics argued, then and now, that Curtis wasn’t interested in documenting the reality of Indian life in the 20th century. He used props, seldom worn regalia, and staged atavistic scenes for dramatic effect. All true and beside the point.

Curtis was an artist, not simply a photographer or ethnologist. He would show the world what remained of a people and their culture rather than what had been lost. He wanted Americans to admire his subjects as he did. The viewer, like the reader of a compelling novel, is expected to know that artistic creation is at play in search of a larger truth.

From Curtis’ art and artifice emerged images that are stark, defiant, dignified, heartening, and poignant. You cannot look at his portraits without acknowledging the humanity of his subjects. Here are the people we have defeated, defrauded, and shunted aside. Look at Angeline, who was the daughter of Chief Seattle and who plied the mudflats of the city named after him. She was one of Curtis’ first Native subjects in 1898. Her face is lined with unimaginable cares and unbowed determination. Her very existence is a challenge to the viewer.

Egan, who writes with passion and grace, points out the irony of the Vanishing Race thesis. It wasn’t the Indians who disappeared – far from it. It was instead The North American Indian and its creator that vanished. Curtis finished his final volume in 1930 as the Great Depression was deepening and Indians were the last thing on people’s minds. A complete set cost $3,000 (the equivalent of $40,000 today). King George of England ordered a copy and Carnegie and his lot, but sales didn't come easy. If you wanted to see Indians, you could go to the movies for the cheap Hollywood version.

Curtis – who died in 1952 – and his photographs were largely forgotten for the last two decades of his life. His masterpieces would not be rediscovered for another 20 years, in the 1970s, languishing in a bookshop and a museum in Massachusetts. His work has since been celebrated and exhibited again and commercial reprints are widely available. A complete set of The North American Indian sold for $1.8 million in 2009.

More significant is that tribes today are making use of Curtis’s photographic and ethnographic work to learn, teach, and inspire. The Hopi, for example, purchased an original edition of Volume XII, which is devoted to the tribe and contains valuable information on their history, language, songs, and traditions. It is hard to put a price on that.

This review by David Holahan was originally published in the Christian Science Monitor on October 15, 2012. Holahan is a regular contributor to the Monitor's Books section.