Merrilee Rush: Seattle’s homegrown rock ‘n’ roll sweetheart

September 1, 2020 at 1:00 p.m. | Updated March 7, 2022 at 12:20 a.m.

All photos courtesy of Merrilee Rush

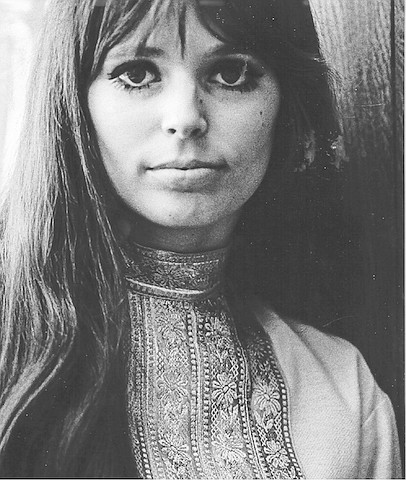

Merrilee Rush gained national fame in 1968 with her breakout hit song, Angel of the Morning, which earned her a Grammy nomination for female vocalist of the year.

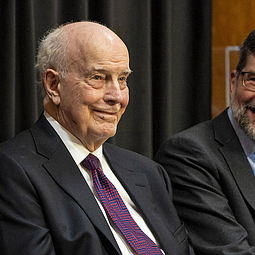

Before that, Merrilee was already well-known on the northwest’s thriving teen dance circuit playing packed venues like the Spanish Castle on Pacific Highway and Parker’s on Aurora. She and her bands cut records, found radio play and were popular draws on the circuit. In short, they were regional celebrities. Then, as award-winning author and rock ‘n’ roll aficionado Peter Blecha writes: “...after scoring her first of several international radio hits, Angel of the Morning, she was no longer Seattle’s private treasure and the years of major-label record deals, television appearances and concert touring began.”

Merrilee spends time these days on her historic farm outside of Redmond. She is surrounded by 22 lush acres and a small “herd” of Old English Sheepdogs, a breed she’s been raising for 60 years.

“I couldn’t ask for a better place to be in quarantine,” says Merrilee of the pastoral surroundings she calls home. It’s a place she’s known her entire life—Merrilee’s grandfather built the farm in 1906.

Since she is at higher risk due to asthma from years of performing in smoky bars, her husband— rhythm and blues musician Billy Mac—does all the shopping. He also takes care of the land.

“Billy Mac never signed up for this,” laughs Merrilee about her city-bred husband. “But it’s a special place,” she says of the farm. “He’s cared for it all these years and it has gone through such a transformation. It’s a work of love.” According to Merrilee, Billy Mac not only loves the farm, but the New Orleans native has also learned to love lawn tractors.

“I grew up coming out to this farm. I actually lived here after I was born when my dad was stationed in England during WWII,” she reports.

The family home was in Lake Forest Park, just north of Seattle. Merrilee, then Merrilee Gunst, enjoyed an idyllic childhood with three younger sisters and a much younger brother. She studied classical piano for 10 years.

By age 13, Merrilee was performing at talent contests and local USO shows entertaining military troops. She often accompanied her friends on the piano while they sang. “I’m playing the Bumble Boogie,” she recalls. “But they stand up and sing in their pretty dresses and get all the applause. I told myself, I need to think about being a singer!”

Although she never thought she’d actually become an entertainer, she was always passionate about music— especially listening to the radio and watching American Bandstand. “That’s how I learned to dance.”

Soon enough, she herself would be performing in front of those dancing kids on the classic rock ‘n roll TV program.

When rock entered her life, she quickly gave up the idea of being a classical pianist. “Classical music is intensive; your life is consumed with it. Rock is so direct and simple,” says Merrilee.

In 1960, when she was only 16, her friends wanted to audition as singers for a band from Renton called The Amazing Aztecs led by saxophonist Neil Rush (an older man at age 18). Merrilee came along to accompany her friends on the piano while they auditioned.

Neil Rush asked Merrilee if she could sing. “I loved singing harmony, but never thought I had the wherewithal to be a lead singer.” She claims that when she started, she wasn’t a good singer. Still, she got the job.

There was disagreement within the band about her role and the Aztecs fell apart. Neil Rush and Merrilee, under her parents’ watchful eyes, went on to form other bands together, starting with Merrilee and Her Men. She soon traded in her piano for a Hammond organ when the two joined a thriving Burien-based band, the Statics, led by Doo Wop singer “Tiny Tony” Smith. The band was known for R&B music and choreographed steps.

“We were show bands and we always liked to concentrate on personalities,” says Merrilee. She attributes the focus on personality to the great radio stations in the northwest. “We had KJR, which was personality jocks combined with music... guys talking to you being funny and personable. They brought something more than music to the program. I think radio had a big influence on how we trained to interact with the audience,” she recalls.

Merrilee first started performing during the era of Duke of Earl, Elvis and Little Richard. The bands played what was on the radio at the time; as she continued to perform, the repertoire expanded to stay current with popular music.

“At that time, rhythm and blues was big in the northwest,” reflects Merrilee. “Tina Turner was my favorite of all time. The action was so essential... people might remember what they saw more than what they heard. When Tina and Ike Turner, Bobby Bland or James Brown came to town, we always went see them.”

Then came the Beatles.

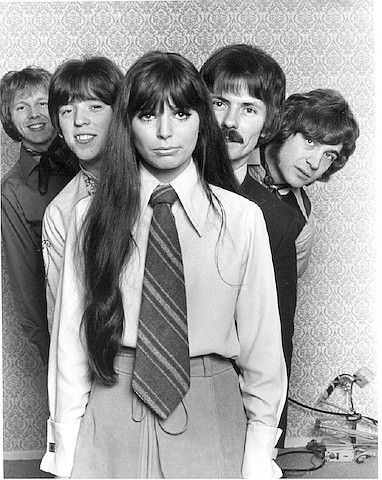

Merrilee says that Beatlemania killed the rockin’ R&B music she was playing and that had been so popular in the Northwest. “Everybody had to become a pop band! So Neil and I left the Statics,” and in 1965 they formed a new group, Merrilee and the Turnabouts.

By then, Merrilee and Neil Rush were an official couple—they married on July 1, 1963 and the following year had a son, Michael.

“My dad was a builder and he built us a house right across the street from them,” said Merrilee. The arrangement worked well. Merrilee and the Turnabouts were booked every weekend on the circuit of teen dance venues from Seattle to Spokane, Idaho and Oregon. While Merrilee and Neil Rush performed, her parents took care of Michael, who had a built-in ‘brother’ at his grandparents’ house.

“My brother Clay was only one year older than Michael,” reports Merrilee. “My parents tried and tried for a boy and got four girls. When they stopped trying, they finally got Clay.” Interestingly, Merrilee’s brother and her son played together on the same team in school. “Michael was a great athlete growing up,” she adds. He also became a keyboard player and singer just like his mom.

“It’s all a blur,” admits Merrilee of the teen dance years. “We were playing to huge crowds. There were some ballrooms, but also roller-skating rinks and airplane hangars and even horse roping arenas.” She recalls one place with a dirt floor, the dancing kids kicking up dust, dirt swirling in the air while she sang. Another time, kids set off fireworks inside the hangar during the show.

Her life took a major turn when one of their roadies went to work with Paul Revere and the Raiders, another popular northwest-based band. The Raiders were enjoying great success and planned a major tour in the deep south. The roadie recommended Merrilee’s band as an opening act for the Raiders.

At the end of the tour, the Raiders were cutting their next album in Memphis, Goin’ to Memphis, and Merrilee tagged along. Hit-maker Chips Moman, who was producing the Raiders’ album, asked her to record some demo songs. He liked her voice and invited her to come back a month later. That is when she recorded Angel of the Morning, with the same crew of great session musicians who backed Elvis’ Memphis recordings. “I was very lucky to be in that studio,” she told Jake Uitti of KEXP radio.

Angel of the Morning was undeniably successful; Merrilee became a star, with opportunities popping up left and right.

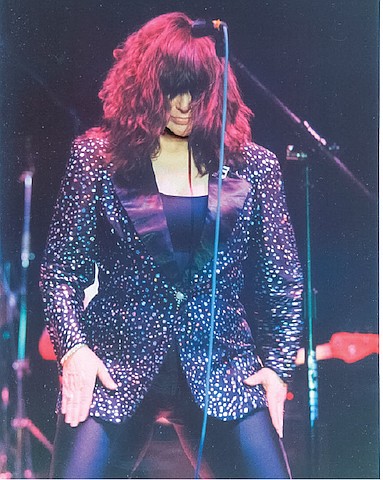

“When Angel hit, I started doing TV in Los Angeles,” remembers Merrilee. She really enjoyed the work. She was impressed at how professional the television crew was—not like the casual atmosphere she was used to, where things might be slapped together with duct tape. Merrilee appeared on American Bandstand, The Johnny Cash Show, the Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, Steve Allen’s show and many others. “I’d do my glamor thing in L.A. then come home and play the dance circuit again.”

The record deals started, too. “I was so green, so inexperienced in the recording industry,” says Merrilee. “There was no real follow-up on Angel, no capitalization on that hit.” She cut more songs, but the company went under. “I just didn’t know anything about the business end of the music industry.”

Recording was an adjustment. She was used to performing live before an audience. “They pitched songs and we chose from them, but they weren’t the songs I would have chosen for myself. They wanted me to sing sweet, but that was only one side of me. Our shows were rock and energetic.”

She recalls putting together a performance at the end of production for one of the albums. All the people from the record label were there and they watched her perform in her usual rocking style. The producer realized they’d been “cutting her all wrong,” she said in the KEXP interview. “But I never felt that was something I could complain about. I just did the recordings.”

Despite her disappointments with the recording industry, Merrilee was still riding high on Angel and her other records when, in 1971, she was booked in Las Vegas.

“I didn’t like Vegas at all,” she states. “We were doing the same show two or three times a night. Everything is written out and you can’t deviate from it. We were in a small showroom off the casino and had to keep the volume down or else the pit bosses would scream at us for being too loud.” It was a delicate balance, trying to keep up the energy in the room for the people who came to dance, and having to keep the volume down for the gamblers. “And it was the same thing every night,” says Merrilee. “We were used to rocking out and constantly learning new tunes, keeping it fresh.” Vegas didn’t suit her.

What had suited her was the dance circuit. Although it was a rigorous schedule, Merrilee calls the teen dances back home “a wonderful playground.” She knew what she was doing, the crowds were fun, she had control over the performances and received feedback from the audience. But by the time she returned from Vegas, the teen dances had dissipated. Unfortunately, that meant playing in clubs and bars instead.

“I never drank or smoked, so going into these rooms...I hated it.” She had signed on with the William Morris agency, which had successfully booked her on TV, but they didn’t know how to book her on concert tours. And performing was what she liked to do.

Merrilee did keep recording and touring the clubs for many long years. But, finally, she had enough. She retreated into the old farmhouse on her grandfather’s farm.

Reflecting on the “olden days,” Merrilee says, “Playing the teenage dances and getting to rock out was my favorite, it was heaven. The clubs weren’t as much fun. That northwest dance scene meant there was work for everybody. Bands could stay together,” she adds. “We were lucky to have that. I think we had the best teen dances anywhere in the country.”

Touring and playing the clubs wasn’t all bad, though. She met people from across the country she would never had known, including her future husband—musician and songwriter Billy Mac. Fate introduced them. They began touring together. Along the way, they married.

Until the pandemic, Billy Mac continued to perform five nights a week, four hours a night. Although he’s had to have vocal cord surgery, he has “an extremely durable voice,” says Merrilee. “He has a raspy, sexy voice. He’s amazing,” she adds. Not only has her talented husband learned to fix lawn tractors, when COVID put his performing career on hold, he started setting up a video recording studio to go online with shows. “He’s a Brainiac,” says Merrilee “A jack-of-all trades, a renaissance man.”

Billy Mac walks into the room as Merrilee is describing him. “People see her and think she is the sweetest person,” he says of Merrilee. “But what they don’t know is that she really is one of the gentlest, sweetest, most irrepressibly joyful people. Merrilee is greatest thing that has ever happened to me.” He then adds, “Just the facts, ma’am.”

Merrilee responds with, “He is my prince charming.”

For years, the two put on an annual concert on the farm, the MacFest, with musicians gathering from all over, taking turns performing for each other. They hope the tradition might continue once the pandemic is behind us.

Merrilee still performs occasionally. She also enjoys participating in the “Golden Oldies” concerts that continue to pop up over the years. “If they call to put me on a nostalgia show, I am there,” she avows. In 1989, the Northwest Area Musicians’ Association (NAMA) honored Rush with membership in the NAMA Hall of Fame.

Merrilee says the only singing she’s doing these days is when she gets on the treadmill, puts in the earbuds and sings along.

Does she have any advice to Northwest Prime Time readers? “Keep moving! Keep moving forward. As they say, ‘Use it or lose it.’ Rest is really important, too. It’s an ebb and flow.” She adds, “Music has such an impact on your psyche. People should listen to music that makes them happy.”

Rock on.

More Information

To purchase Merrilee Rush’s CD, which includes Angel of the Morning and other favorites, visit Billy Mac’s online store at shop.billymac.com/main.sc. You will find Merrilee’s CD and posters, along with Billy Mac’s music and more.

“I couldn’t ask for a better place to be in quarantine,” says Merrilee of the pastoral surroundings she calls home. It’s a place she’s known her entire life—Merrilee’s grandfather built the farm in 1906.

Since she is at higher risk due to asthma from years of performing in smoky bars, her husband— rhythm and blues musician Billy Mac—does all the shopping. He also takes care of the land.

“Billy Mac never signed up for this,” laughs Merrilee about her city-bred husband. “But it’s a special place,” she says of the farm. “He’s cared for it all these years and it has gone through such a transformation. It’s a work of love.” According to Merrilee, Billy Mac not only loves the farm, but the New Orleans native has also learned to love lawn tractors.

“I grew up coming out to this farm. I actually lived here after I was born when my dad was stationed in England during WWII,” she reports.

The family home was in Lake Forest Park, just north of Seattle. Merrilee, then Merrilee Gunst, enjoyed an idyllic childhood with three younger sisters and a much younger brother. She studied classical piano for 10 years.

By age 13, Merrilee was performing at talent contests and local USO shows entertaining military troops. She often accompanied her friends on the piano while they sang. “I’m playing the Bumble Boogie,” she recalls. “But they stand up and sing in their pretty dresses and get all the applause. I told myself, I need to think about being a singer!”

Although she never thought she’d actually become an entertainer, she was always passionate about music— especially listening to the radio and watching American Bandstand. “That’s how I learned to dance.”

Soon enough, she herself would be performing in front of those dancing kids on the classic rock ‘n roll TV program.

When rock entered her life, she quickly gave up the idea of being a classical pianist. “Classical music is intensive; your life is consumed with it. Rock is so direct and simple,” says Merrilee.

In 1960, when she was only 16, her friends wanted to audition as singers for a band from Renton called The Amazing Aztecs led by saxophonist Neil Rush (an older man at age 18). Merrilee came along to accompany her friends on the piano while they auditioned.

Neil Rush asked Merrilee if she could sing. “I loved singing harmony, but never thought I had the wherewithal to be a lead singer.” She claims that when she started, she wasn’t a good singer. Still, she got the job.

There was disagreement within the band about her role and the Aztecs fell apart. Neil Rush and Merrilee, under her parents’ watchful eyes, went on to form other bands together, starting with Merrilee and Her Men. She soon traded in her piano for a Hammond organ when the two joined a thriving Burien-based band, the Statics, led by Doo Wop singer “Tiny Tony” Smith. The band was known for R&B music and choreographed steps.

“We were show bands and we always liked to concentrate on personalities,” says Merrilee. She attributes the focus on personality to the great radio stations in the northwest. “We had KJR, which was personality jocks combined with music... guys talking to you being funny and personable. They brought something more than music to the program. I think radio had a big influence on how we trained to interact with the audience,” she recalls.

Merrilee first started performing during the era of Duke of Earl, Elvis and Little Richard. The bands played what was on the radio at the time; as she continued to perform, the repertoire expanded to stay current with popular music.

“At that time, rhythm and blues was big in the northwest,” reflects Merrilee. “Tina Turner was my favorite of all time. The action was so essential... people might remember what they saw more than what they heard. When Tina and Ike Turner, Bobby Bland or James Brown came to town, we always went see them.”

Then came the Beatles.

Merrilee says that Beatlemania killed the rockin’ R&B music she was playing and that had been so popular in the Northwest. “Everybody had to become a pop band! So Neil and I left the Statics,” and in 1965 they formed a new group, Merrilee and the Turnabouts.

By then, Merrilee and Neil Rush were an official couple—they married on July 1, 1963 and the following year had a son, Michael.

“My dad was a builder and he built us a house right across the street from them,” said Merrilee. The arrangement worked well. Merrilee and the Turnabouts were booked every weekend on the circuit of teen dance venues from Seattle to Spokane, Idaho and Oregon. While Merrilee and Neil Rush performed, her parents took care of Michael, who had a built-in ‘brother’ at his grandparents’ house.

“My brother Clay was only one year older than Michael,” reports Merrilee. “My parents tried and tried for a boy and got four girls. When they stopped trying, they finally got Clay.” Interestingly, Merrilee’s brother and her son played together on the same team in school. “Michael was a great athlete growing up,” she adds. He also became a keyboard player and singer just like his mom.

“It’s all a blur,” admits Merrilee of the teen dance years. “We were playing to huge crowds. There were some ballrooms, but also roller-skating rinks and airplane hangars and even horse roping arenas.” She recalls one place with a dirt floor, the dancing kids kicking up dust, dirt swirling in the air while she sang. Another time, kids set off fireworks inside the hangar during the show.

Her life took a major turn when one of their roadies went to work with Paul Revere and the Raiders, another popular northwest-based band. The Raiders were enjoying great success and planned a major tour in the deep south. The roadie recommended Merrilee’s band as an opening act for the Raiders.

At the end of the tour, the Raiders were cutting their next album in Memphis, Goin’ to Memphis, and Merrilee tagged along. Hit-maker Chips Moman, who was producing the Raiders’ album, asked her to record some demo songs. He liked her voice and invited her to come back a month later. That is when she recorded Angel of the Morning, with the same crew of great session musicians who backed Elvis’ Memphis recordings. “I was very lucky to be in that studio,” she told Jake Uitti of KEXP radio.

Angel of the Morning was undeniably successful; Merrilee became a star, with opportunities popping up left and right.

“When Angel hit, I started doing TV in Los Angeles,” remembers Merrilee. She really enjoyed the work. She was impressed at how professional the television crew was—not like the casual atmosphere she was used to, where things might be slapped together with duct tape. Merrilee appeared on American Bandstand, The Johnny Cash Show, the Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, Steve Allen’s show and many others. “I’d do my glamor thing in L.A. then come home and play the dance circuit again.”

The record deals started, too. “I was so green, so inexperienced in the recording industry,” says Merrilee. “There was no real follow-up on Angel, no capitalization on that hit.” She cut more songs, but the company went under. “I just didn’t know anything about the business end of the music industry.”

Recording was an adjustment. She was used to performing live before an audience. “They pitched songs and we chose from them, but they weren’t the songs I would have chosen for myself. They wanted me to sing sweet, but that was only one side of me. Our shows were rock and energetic.”

She recalls putting together a performance at the end of production for one of the albums. All the people from the record label were there and they watched her perform in her usual rocking style. The producer realized they’d been “cutting her all wrong,” she said in the KEXP interview. “But I never felt that was something I could complain about. I just did the recordings.”

Despite her disappointments with the recording industry, Merrilee was still riding high on Angel and her other records when, in 1971, she was booked in Las Vegas.

“I didn’t like Vegas at all,” she states. “We were doing the same show two or three times a night. Everything is written out and you can’t deviate from it. We were in a small showroom off the casino and had to keep the volume down or else the pit bosses would scream at us for being too loud.” It was a delicate balance, trying to keep up the energy in the room for the people who came to dance, and having to keep the volume down for the gamblers. “And it was the same thing every night,” says Merrilee. “We were used to rocking out and constantly learning new tunes, keeping it fresh.” Vegas didn’t suit her.

What had suited her was the dance circuit. Although it was a rigorous schedule, Merrilee calls the teen dances back home “a wonderful playground.” She knew what she was doing, the crowds were fun, she had control over the performances and received feedback from the audience. But by the time she returned from Vegas, the teen dances had dissipated. Unfortunately, that meant playing in clubs and bars instead.

“I never drank or smoked, so going into these rooms...I hated it.” She had signed on with the William Morris agency, which had successfully booked her on TV, but they didn’t know how to book her on concert tours. And performing was what she liked to do.

Merrilee did keep recording and touring the clubs for many long years. But, finally, she had enough. She retreated into the old farmhouse on her grandfather’s farm.

“I couldn’t ask for a better place to be in quarantine,” says Merrilee of the pastoral surroundings she calls home. It’s a place she’s known her entire life—Merrilee’s grandfather built the farm in 1906.

Since she is at higher risk due to asthma from years of performing in smoky bars, her husband— rhythm and blues musician Billy Mac—does all the shopping. He also takes care of the land.

“Billy Mac never signed up for this,” laughs Merrilee about her city-bred husband. “But it’s a special place,” she says of the farm. “He’s cared for it all these years and it has gone through such a transformation. It’s a work of love.” According to Merrilee, Billy Mac not only loves the farm, but the New Orleans native has also learned to love lawn tractors.

“I grew up coming out to this farm. I actually lived here after I was born when my dad was stationed in England during WWII,” she reports.

The family home was in Lake Forest Park, just north of Seattle. Merrilee, then Merrilee Gunst, enjoyed an idyllic childhood with three younger sisters and a much younger brother. She studied classical piano for 10 years.

By age 13, Merrilee was performing at talent contests and local USO shows entertaining military troops. She often accompanied her friends on the piano while they sang. “I’m playing the Bumble Boogie,” she recalls. “But they stand up and sing in their pretty dresses and get all the applause. I told myself, I need to think about being a singer!”

Although she never thought she’d actually become an entertainer, she was always passionate about music— especially listening to the radio and watching American Bandstand. “That’s how I learned to dance.”

Soon enough, she herself would be performing in front of those dancing kids on the classic rock ‘n roll TV program.

When rock entered her life, she quickly gave up the idea of being a classical pianist. “Classical music is intensive; your life is consumed with it. Rock is so direct and simple,” says Merrilee.

In 1960, when she was only 16, her friends wanted to audition as singers for a band from Renton called The Amazing Aztecs led by saxophonist Neil Rush (an older man at age 18). Merrilee came along to accompany her friends on the piano while they auditioned.

Neil Rush asked Merrilee if she could sing. “I loved singing harmony, but never thought I had the wherewithal to be a lead singer.” She claims that when she started, she wasn’t a good singer. Still, she got the job.

There was disagreement within the band about her role and the Aztecs fell apart. Neil Rush and Merrilee, under her parents’ watchful eyes, went on to form other bands together, starting with Merrilee and Her Men. She soon traded in her piano for a Hammond organ when the two joined a thriving Burien-based band, the Statics, led by Doo Wop singer “Tiny Tony” Smith. The band was known for R&B music and choreographed steps.

“We were show bands and we always liked to concentrate on personalities,” says Merrilee. She attributes the focus on personality to the great radio stations in the northwest. “We had KJR, which was personality jocks combined with music... guys talking to you being funny and personable. They brought something more than music to the program. I think radio had a big influence on how we trained to interact with the audience,” she recalls.

Merrilee first started performing during the era of Duke of Earl, Elvis and Little Richard. The bands played what was on the radio at the time; as she continued to perform, the repertoire expanded to stay current with popular music.

“At that time, rhythm and blues was big in the northwest,” reflects Merrilee. “Tina Turner was my favorite of all time. The action was so essential... people might remember what they saw more than what they heard. When Tina and Ike Turner, Bobby Bland or James Brown came to town, we always went see them.”

Then came the Beatles.

Merrilee says that Beatlemania killed the rockin’ R&B music she was playing and that had been so popular in the Northwest. “Everybody had to become a pop band! So Neil and I left the Statics,” and in 1965 they formed a new group, Merrilee and the Turnabouts.

By then, Merrilee and Neil Rush were an official couple—they married on July 1, 1963 and the following year had a son, Michael.

“My dad was a builder and he built us a house right across the street from them,” said Merrilee. The arrangement worked well. Merrilee and the Turnabouts were booked every weekend on the circuit of teen dance venues from Seattle to Spokane, Idaho and Oregon. While Merrilee and Neil Rush performed, her parents took care of Michael, who had a built-in ‘brother’ at his grandparents’ house.

“My brother Clay was only one year older than Michael,” reports Merrilee. “My parents tried and tried for a boy and got four girls. When they stopped trying, they finally got Clay.” Interestingly, Merrilee’s brother and her son played together on the same team in school. “Michael was a great athlete growing up,” she adds. He also became a keyboard player and singer just like his mom.

“It’s all a blur,” admits Merrilee of the teen dance years. “We were playing to huge crowds. There were some ballrooms, but also roller-skating rinks and airplane hangars and even horse roping arenas.” She recalls one place with a dirt floor, the dancing kids kicking up dust, dirt swirling in the air while she sang. Another time, kids set off fireworks inside the hangar during the show.

Her life took a major turn when one of their roadies went to work with Paul Revere and the Raiders, another popular northwest-based band. The Raiders were enjoying great success and planned a major tour in the deep south. The roadie recommended Merrilee’s band as an opening act for the Raiders.

At the end of the tour, the Raiders were cutting their next album in Memphis, Goin’ to Memphis, and Merrilee tagged along. Hit-maker Chips Moman, who was producing the Raiders’ album, asked her to record some demo songs. He liked her voice and invited her to come back a month later. That is when she recorded Angel of the Morning, with the same crew of great session musicians who backed Elvis’ Memphis recordings. “I was very lucky to be in that studio,” she told Jake Uitti of KEXP radio.

Angel of the Morning was undeniably successful; Merrilee became a star, with opportunities popping up left and right.

“When Angel hit, I started doing TV in Los Angeles,” remembers Merrilee. She really enjoyed the work. She was impressed at how professional the television crew was—not like the casual atmosphere she was used to, where things might be slapped together with duct tape. Merrilee appeared on American Bandstand, The Johnny Cash Show, the Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, Steve Allen’s show and many others. “I’d do my glamor thing in L.A. then come home and play the dance circuit again.”

“I couldn’t ask for a better place to be in quarantine,” says Merrilee of the pastoral surroundings she calls home. It’s a place she’s known her entire life—Merrilee’s grandfather built the farm in 1906.

Since she is at higher risk due to asthma from years of performing in smoky bars, her husband— rhythm and blues musician Billy Mac—does all the shopping. He also takes care of the land.

“Billy Mac never signed up for this,” laughs Merrilee about her city-bred husband. “But it’s a special place,” she says of the farm. “He’s cared for it all these years and it has gone through such a transformation. It’s a work of love.” According to Merrilee, Billy Mac not only loves the farm, but the New Orleans native has also learned to love lawn tractors.

“I grew up coming out to this farm. I actually lived here after I was born when my dad was stationed in England during WWII,” she reports.

The family home was in Lake Forest Park, just north of Seattle. Merrilee, then Merrilee Gunst, enjoyed an idyllic childhood with three younger sisters and a much younger brother. She studied classical piano for 10 years.

By age 13, Merrilee was performing at talent contests and local USO shows entertaining military troops. She often accompanied her friends on the piano while they sang. “I’m playing the Bumble Boogie,” she recalls. “But they stand up and sing in their pretty dresses and get all the applause. I told myself, I need to think about being a singer!”

Although she never thought she’d actually become an entertainer, she was always passionate about music— especially listening to the radio and watching American Bandstand. “That’s how I learned to dance.”

Soon enough, she herself would be performing in front of those dancing kids on the classic rock ‘n roll TV program.

When rock entered her life, she quickly gave up the idea of being a classical pianist. “Classical music is intensive; your life is consumed with it. Rock is so direct and simple,” says Merrilee.

In 1960, when she was only 16, her friends wanted to audition as singers for a band from Renton called The Amazing Aztecs led by saxophonist Neil Rush (an older man at age 18). Merrilee came along to accompany her friends on the piano while they auditioned.

Neil Rush asked Merrilee if she could sing. “I loved singing harmony, but never thought I had the wherewithal to be a lead singer.” She claims that when she started, she wasn’t a good singer. Still, she got the job.

There was disagreement within the band about her role and the Aztecs fell apart. Neil Rush and Merrilee, under her parents’ watchful eyes, went on to form other bands together, starting with Merrilee and Her Men. She soon traded in her piano for a Hammond organ when the two joined a thriving Burien-based band, the Statics, led by Doo Wop singer “Tiny Tony” Smith. The band was known for R&B music and choreographed steps.

“We were show bands and we always liked to concentrate on personalities,” says Merrilee. She attributes the focus on personality to the great radio stations in the northwest. “We had KJR, which was personality jocks combined with music... guys talking to you being funny and personable. They brought something more than music to the program. I think radio had a big influence on how we trained to interact with the audience,” she recalls.