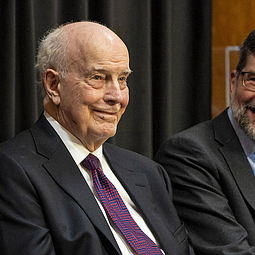

With tears in his eyes, Seattle University Professor Emeritus, Bob Harmon, recalls “There were 190 soldiers in my company. I was one out of 17 who made it.”

Bob Harmon, a Private First Class (PFC) fought in the Battle of Normandy, the Battle of the Bulge and served as one of the Monuments Men recovering artwork and treasures stolen by the Nazis.

During the Battle of the Bulge (Dec. 16, 1944 through Jan. 25, 1945), Bob lived in foxholes. “We were constantly scared of artillery and mortar fire.”

Sometimes he and his men took over a farmhouse. He recalls discovering smoked ham in a chimney of one of those houses. With potatoes and carrots he found in a nearby field, he prepared a nutritious meal. He also cooked for the family, who had been ordered to move to the basement for safety.

Harmon was known as a good cook among his unit and often heard, “Harmon! Cook up dinner!”

Bob was motivated throughout the war to not only stay alive, but “to fight for the guy on your left and your right.” He added, “Infantry fighting is done through crawling.”

He describes a day where he and one other soldier crawled on their bellies through the Siegfried Line to behind German bunkers. The army taught the American military just enough German so they could communicate with the enemy. After a barrage of Allied fire hit the bunker, Bob told the Germans left alive, “Der Krieg ist verloren” (The war is lost). “You have a life to save.”

After the war, soldiers returned to civilian life. Tom Brokaw, in his book, The Greatest Generation, noted WWII soldiers came home, persevered, went back to school and worked. Bob was no exception.

“Very few people talked about what they did in the war,” he said. “We were sick of war and there was so much else to do. I wanted to go to college on the GI Bill and meet girls.”

But when he returned home to Olympia, it helped that he was from a military family where he, along with his dad and uncle, could openly share war stories. He admitted not knowing if he suffered from PTSD, but felt sharing stories helped. He feels he is still transitioning from wartime to the present.

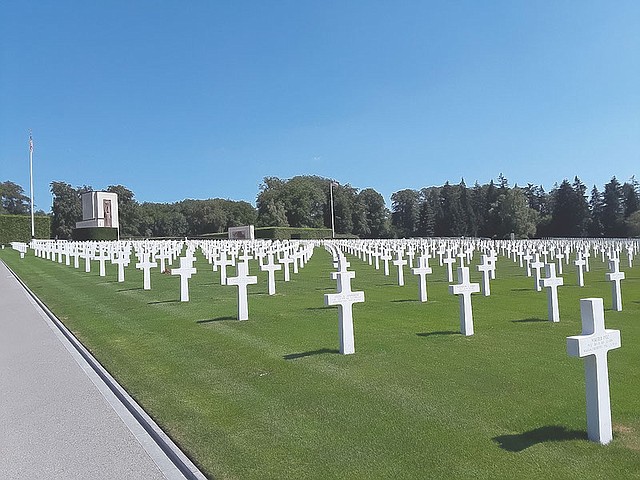

Bob has returned to the battlefields in Europe with Virginia, his wife of 67 years, and their four children. He’s given presentations at both European venues and to military academies in the United States. The country of Luxembourg and the state of Thuringia, Germany, have bestowed honorary citizenship on him in recognition of his efforts during the war. He’s visited the present-day Luxembourg American Cemetery and Memorial, where on December 29, 1944, a military burial ground first appeared.

Today, white crosses and Stars of David on 50 acres bring lasting peace to 5,076 American soldiers. Most of them died between December 1944 and January 1945 while fighting the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium. On this hallowed ground, one small white cross inscribed with “General George S. Patton” faces the troops.

Bob walked among the crosses in this cemetery and notes, “The first rays of the morning sun always hit Patton’s cross first.”

Bob served under General Patton’s Third Army, 319th Infantry Regiment, 80th Division. His knowledge of a young Patton comes through stories his uncle, Jeff Willis, told him.

“My uncle played polo on horses with Patton when they were on assignment in Hawaii. Patton was a first-class polo player,” said Harmon. His uncle also divulged, “Patton was mouthy and cursing all the time.” Bob also knows General Patton’s granddaughter, who “sang and entertained the troops,” he said.

One of his favorite topics to discuss is the Monuments Men. Towards the end of the war, in February 1945, Bob was assigned to work with the Arts and Monuments Commission. Altaussee, Austria, was loaded with salt mines, including Sternberg, Hitler’s special mine, where Nazis hid stolen artwork and treasurers. Bob recalls discovering not only artwork, but also a complete library and Australian coins.

When his unit came across Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna, they were specifically ordered, “Don’t touch that!”

“We all touched it.”

Bob said of his military service, “I was a good rifleman in the infantry,” but admits, he didn’t develop leadership skills until much later. Now a leader and military history expert, he served on the history faculty and in administration at Seattle University from 1953 to 2013 and earned the distinction of Professor Emeritus.

Professor Harmon, a vibrant 93-year-old, still gives presentations and grants interviews – always the educator!