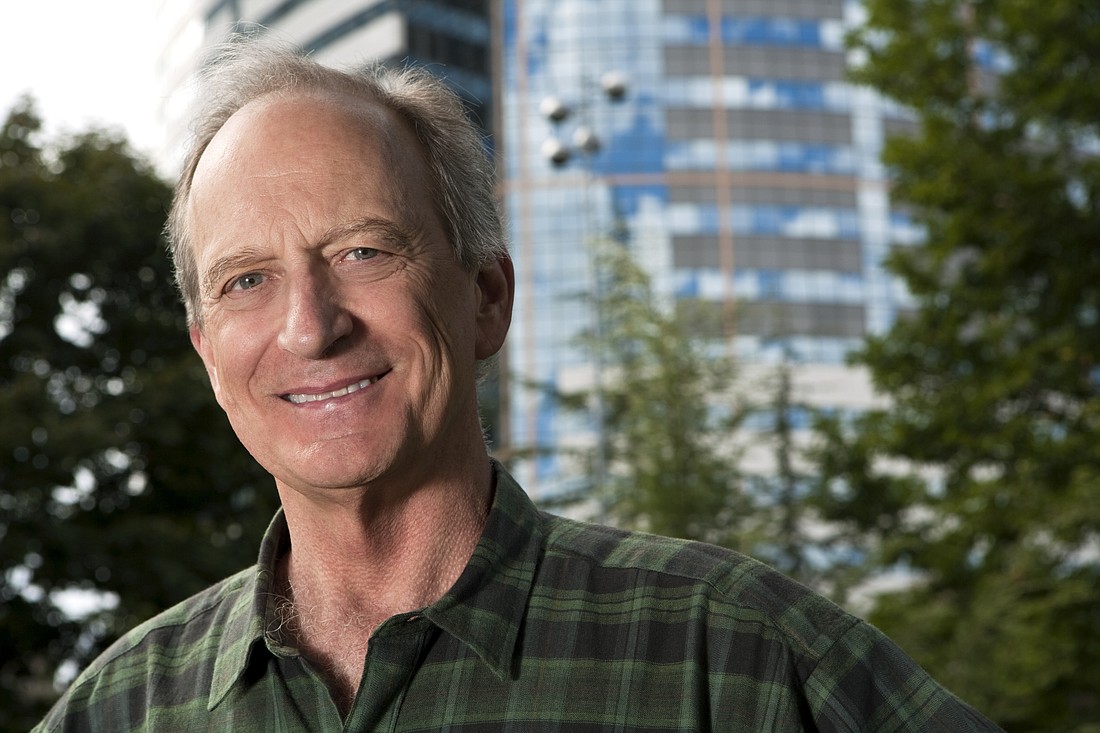

Denis Hayes – Environmental Activist Extraordinaire

March 31, 2014 at 12:00 a.m.

It’s not often you meet someone who says they face each day excited about the work that lies before them.

So it is with Denis Hayes, prominent environmental activist, national coordinator of the first Earth Day, and president of the Seattle-based Bullitt Foundation since 1992.

“I have the gigantic good fortune to get up in the morning and work on something I care about,” proclaims Denis with infectious enthusiasm.

To engage Denis Hayes in conversation is to enter into his world for a moment and become inspired by the many things that clearly light his fire. This articulate, highly intelligent and thoughtful man speaks with passion and conviction that both compels and energizes.

The Hayes family moved from Espinola, Ontario to Camas, Washington in 1950. It was here, growing up a stone’s throw from the banks of the Columbia River, that Denis began to cultivate a love for nature and the outdoors.

Denis’ father made his living at the local paper mill as was the case with most men of that time and place. Denis recalls his father held hard-working conservative values. He also possessed a certain stoic pride in his role as the operator of paper machine number 10, which was responsible for producing paper that wrapped frozen food products.

To Denis’ father and the rest of the town, the sulfur dioxide and other chemical pollutants thrown off by the paper mill were tolerated as “the smell of prosperity.” As Denis recalls, nobody at the time realized the inordinate amount of rust and corrosion destroying their automobiles was the same stuff they were breathing. In addition to premature deaths associated with the pollution, most working men were deaf by the age of 50 or 55 due to the thunderous noise from the equipment they worked with at the mill.

“For the first seventeen years of my life,” recalls Denis, “I had a nagging sore throat.” However, this did not stop him from hopping on his bike to explore the surrounding Columbia River basin, or hiking through the nearby forests. Denis remembers exploring green verdant forests, only to be suddenly disoriented by stumbling across a clear-cut wasteland, or “moonscape” in his parlance, that had been sacrificed to feed the mill. “[The mill was] a great digesting machine, continually devouring the forests we’d go hiking in,” he explains.

Denis remembers a happy childhood growing up in Camas. The forty-mile round-trip bicycle ride to the Beacon Rock area of the Columbia River was, and continues to be, one of the most beautiful natural spots in the world to Denis.

One of many pivotal moments in his life took place in 1961 as a junior at Camas High School (now named for him). Denis enrolled in an Ecology Seminar where he read Eugene Odum’s classic text Fundamentals of Ecology. “This was before we even had a vocabulary for ecology as we now understand it, but it was still an important moment for me,” says Denis. The seeds were planted that would shape the values by which Denis has made and continues to make a global impact on the relationship humans have with this blue and green globe we call home.

As his teenaged years unfolded into adulthood, Denis spent two years at Clark Community College before deciding to hitchhike around the world. A feverish bug for adventure and world travel had fully settled in.

After failing to get a job on a round-the-world cargo-ship, Denis managed to secure a $99 passage on a vessel headed to Hawaii. He lived the carefree life of a Waikiki surfer for a while and worked as a disc jockey at KNDI radio station in Honolulu.

Eventually, Denis managed to get himself to Japan, where his ‘round-the-world adventure continued. A job as an assistant at a swimming pool led to a position as director of an athletic club. With savings amassed over the summer, Denis, at age 20, began a hitchhiking odyssey that took him all over the world. He has visited over 140 countries in his lifetime.

Denis traversed places that today would be unthinkable for their instability and threat to Americans. But in the mid-1960s, it was possible to travel just about anywhere in the world, including (if you were careful) countries behind the Iron Curtain. Denis spent time in Eastern Europe, even train-hopping as far as Siberia on the Trans-Siberian Railway, and hitchhiked through the Middle East.

As he made his way down the West Coast of Africa, via the generosity and hospitality of others, he was reading Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. This seminal work, which explores the dehumanizing effects of colonization, had a profound impact on Denis’ mindset during his travels. “I wanted to experience all the different parts of the world,” exclaims Denis, “and I must honestly confess that most of what I found in developing nations was quite depressing.”

It was in Southwest Africa, a place that is now called Namibia, that Denis experienced a second pivotal, life-changing experience. Indeed, this moment might be defined as a kind of crucible that forged the Denis Hayes we now know, giving him clarity of purpose for how he would spend the rest of his life.

There is a certain timeless beauty to the details of this story that could belong to the mystics and sages of any age. He was out in the middle of the desert and alone. The night sky was clear and encrusted with stars, brilliantly illuminating everything. Denis was very hungry, and as darkness set in, so did a deep chill. At a precise moment in Denis’ memory, a wave of something deep and profound passed through his body. He believes he was experiencing an epiphany—a realization that there must be a way to look for and identify certain organizing principles that explain the world.

“I began to wonder what it would be like if we began to bind ourselves to the principles of ecology,” reflects Denis. At the time, he remembers thinking that wasps make paper “but without all that byproduct crap produced by mills like the one in Camas.” Essentially, that night Denis came to believe in the tenets and values of what we would now call human, industrial and urban ecology, although this vocabulary had yet to take shape in the world.

Denis stayed up all night, alive with a buzzing energy and awareness more powerful than his hunger or cold. As the sun rose in the eastern sky, Denis quite simply declares, “I knew what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.”

Remarkably, he applied to only one university, Stanford, and was accepted. He was drawn there by influential academics connected to the university at that time: the eminent biologist and professor of population studies Paul Ehrlich, and Don Kennedy, who later became president of Stanford.

Denis somewhat shyly admits that when he entered Stanford after his experience in the African desert he was convinced he was coming back to make a real and meaningful impact.

“All I knew was that the ideas of revolutionaries and influential leaders of the 20th century like Lenin, Mao and Guevara hadn’t worked. I thought human ecology offered another way.”

At Stanford, Denis became deeply involved politically. He was elected student body president and became extensively involved in the anti-Vietnam War movement. He was also increasingly passionate about civil rights, pushing Stanford to recruit more African Americans to its hallowed halls of learning—as both students and professors.

Still driven by his pivotal awakening in Africa, Denis knew he wanted to apply his new-found principles to better the world we live in. He felt his skills could best be put to use through the influential spheres of law and government rather than science.

Upon graduating from Stanford, he applied to Harvard University. He was selected, together with other top-performing university undergrads from around the nation, to enroll in what is of what is now called the Masters in Public Policy program at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

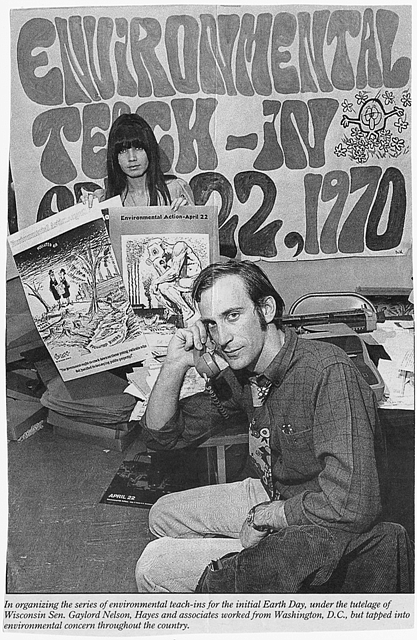

But in the autumn of 1969, something else began stirring. Senator Gaylord Nelson was calling for an environmental teach-in at colleges and universities; and Gladwyn Hill, the first full-time environmental reporter in the nation, wrote about it on The New York Times’ venerable front page.

Denis sought a meeting with Senator Nelson and flew down to Washington DC; what was supposed to be a courtesy appointment turned into a lengthy, impassioned conversation between two like-minded individuals. Pete McCloskey, another politician (who would go on in 1973 to co-author The Endangered Species Act), entered the conversation. Together they persuaded Denis to drop out of Harvard to organize a major nationwide event to promote environmental awareness on university campuses.

At that time, interest in environmental and ecological issues, though growing, was still fairly tepid on college campuses. It was Denis’ decision to rename the environmental teach-in “Earth Day” and move it mostly off college campuses and into the broader community.

On April 22, 1970, an estimated 20 million people came together in virtually every city, town, village, and crossroad in the country for the world’s first Earth Day.

Earth Day was another pivotal experience for Denis. “I’m so proud of what we accomplished back then, and what we continue to accomplish. But of course, we still have a long, long way to go.” He went on to oversee the Earth Day Network, a nonprofit that promotes Earth Day and all it stands for. Now recognized in 192 countries, Earth Day is the world’s largest observed secular holiday.

When asked about the tangible impact of Earth Day, Denis points to legislation like The Endangered Species Act, The Clean Water act, the Clean Air Act and the founding of the Environmental Protection Agency, all of which became reality in the early 1970s.

“Earth Day got people talking about the value of the environment, and the importance of its protection and survival for our own survival,” reflects Denis. Earth Day created not only a vocabulary for things we now readily understand like the sustainability of natural ecosystems but also “a public willingness, eagerness even, for environmental issues to be a platform for candidates running for political office.”

Denis reminds us that it was often pro-environment Republicans like Pete McCloskey, Chuck Percy, John Lindsay—even Richard Nixon, who worked with Democrats to make environmental legislation a reality.

“Richard Nixon was a bit tough and old-school—not unlike my dad. He might say, ‘Why whine about a little bit of grit in the air?’ but he created the EPA by Presidential executive order and chose Bill Ruckelshaus to head it,” observes Denis, with a chuckle. “Nixon wasn’t much of an environmentalist, but he was a very savvy politician.”

Denis Hayes was appointed head of the Solar Energy Research Institute during the Carter Administration. When the Reagan Administration slashed 80% of funding for solar energy, Denis went back to Stanford to complete his Juris Doctor degree.

In 1992, the children and heirs of Dorothy Bullitt, founder of KING broadcasting in Seattle, met with Denis as they were considering a more specific focus for the Bullitt Foundation. The conversation went well, and Denis was hired as the Foundation’s president. The Bullitt Foundation’s focus is on “safeguard[ing] the natural environment by promoting responsible human activities and sustainable communities in the Pacific Northwest.” (To learn more about the inspiring work of the Bullitt Foundation, visit www.bullitt.org.)

With his new position, Denis was delighted to return to the region where he grew up. “We are fortunate to live in the most beautiful spot on the planet,” he says.

Part of what inspires him in his work at the Bullitt Foundation is the realization that much more can be done to promote sustainability and environmentally-friendly practices in all aspects of business and industry. “The gap between what is being done today and what is necessary for a genuinely sustainable future is enormous,” he laments.

But there are bright spots. The Bullitt Center, an office building and the foundation’s headquarters, was recently judged “The Greenest Commercial Building in the World” by World Architecture magazine. Located at 1501 East Madison Street in Seattle, the Bullitt Center is the first six-story structure in the world so very efficient that it generates more energy from solar panels on its roof (in the cloudiest major city in the contiguous 48 states!) than it uses. Everything, from its non-toxic building materials to its composting toilets, use of rain for all drinking water, and “irresistible stairway” promotes the greenest, most sustainable building practices available.

“We built The Bullitt Center at a premium of about 25% over the cost of a comparable Class A Office Building, but the next one will be much cheaper, and the hundredth will be much, much cheaper. Somebody has to be first,” says Denis, and that’s a good role for a foundation to play.

On a more personal level, Denis and his wife Gail just completed a book entitled Cowed, about the impact of cows on America. After humans, “cows are the most influential species on our continent,” asserts Denis. “Gail and I are pro-cow-in-moderation. Ninety-three million cows is way too many.” The book, published by Norton, will be out soon.

Denis and Gail have a daughter working as an attorney in Washington DC for the progressive American Constitution Society. Their son-in-law is a former Navy Seal currently working on renewable energy issues with The Boeing Company. Their four-year-old granddaughter, Sheridan, is both “a genius and an athlete!”

When asked if he plans to retire, 69-year-old Denis confesses that he views retirement with dread. He still “jumps out of bed at 5:30 every morning eager to do what I do.” However, he concedes that he owes it to his wife to commit eventually to some form of retirement.

“Having traveled to 120 countries by the time I was 25, I now generally travel only with a purpose. But Gail still has many places on her bucket list” says Denis.

He is looking forward with special eagerness to the 50th anniversary of Earth Day in 2020. “I’ll probably roll it up then,” he confesses. He encourages everyone to get involved in Earth Day activities now and leading up to its Golden Anniversary (www.earthday.org).

When invited to offer some advice for Northwest Prime Time readers, Denis reflects that he comes from a generation that “never trusted anyone over the age of 30.” Now that his generation is running the world, he thinks that is still good advice. “People with authority are always too bound up by perceived constraints. Real change tends to emerge outside the power structure at the grassroots.

People are most free to follow their conscience when they are very young or very old. I’d like to use Earth Day to create a new partnership of my fellow geezers with the young folks now in college or at the start of their careers. Although we’ve made great strides on many environmental issues, the big issues— climate disruption, population growth, the epidemic of extinction, worldwide loss of topsoil, the poisoning of the oceans— continue to worsen.”

Denis pauses for a minute before continuing. “I’ve reluctantly concluded that our ‘leaders’ are simply never going to get it together, not in my lifetime. I’d hoped just once to have a President who wasn’t a bitter disappointment. But it’s not going to happen. Fortunately, our future is in our own hands—especially those of us at the beginning and end of our lives who have the freedom to get out there and make a difference. Like that shoe company in Portland keeps exhorting us, ‘Just do it!’ ”