How to Die in Dignity Without Leaving Your Spouse to Starve

June 30, 2014 at 9:39 a.m.

So where does that leave people unlikely to qualify for Medicaid but unable or unwilling to self-insure? Long-term care insurance, of course.

Opt for the 180-Day Elimination Period

Buying any type of insurance means transferring some type of personal risk to an insurance carrier. Clearly defining the risk you want to transfer and then tailoring a policy to best accomplish that goal is critical to getting the best value.

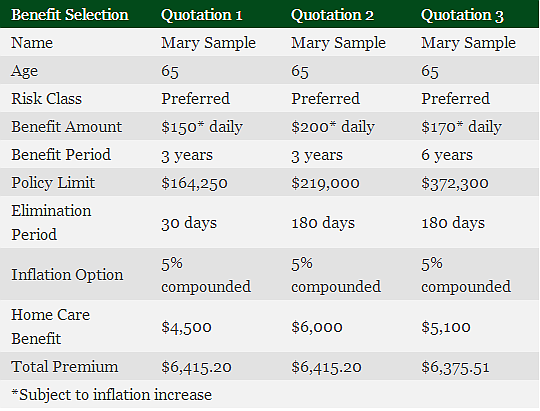

David Holland generously shared some quotes to help illustrate this point. While there are countless long-term care options available today, we’re going to keep this example simple.

Mary Sample is age 65. She wants a policy paying $150 in daily coverage with some inflation protection.

Many advisors would recommend the first policy with the 30-day elimination period, because you might not require care for long periods of time. The 180-day elimination period means you pay for an additional 150 days out of pocket before the insurance company kicks in. The additional cost is $22,500 (150 days x $150/day), and many argue it’s a poor investment because the probability of needing care for three years or longer is small.

On the other hand, the 180-day elimination period (quotes #2 and #3) gives you a lot more coverage for the same premium. In effect, #2 and #3 cost $22,500 more out of pocket in exchange for $54,750 or $208,050 in additional coverage.

The only way to turn the policy premium and additional out-of-pocket costs into a good investment is to require expensive, long-term care. Most of us would prefer to never have to collect a dime. Families with a member requiring years of expensive care would tell you it was one of the best investments they ever made. But insurance is not an investment; it’s a transfer of risk.

The Risk of Leaving Your Spouse Penniless

If a couple has enough assets to be ineligible for Medicaid coverage, a week or two in a nursing home is not the risk they should be transferring. That’s a big nuisance, not a catastrophe. The risk they should transfer is financial ruin for the surviving spouse—in other words, 90 or 180-plus days of care.

Paying insurance premiums for short waiting periods is like buying a $100 deductible on your car instead of a $500 deductible. If you have an accident, you have to make up that gap out of pocket. Your insurance dollars are better spent insuring against the catastrophe, not avoiding the deductible.

Today, Jo and I would opt for door #3. I have two policies: one with a 90-day waiting period and the other, 180 days. I would not recommend anything less than 90 days.

My primary concern is leaving Jo with enough assets to live comfortably for the rest of her life, which could easily be 20-plus years. Paying for 90 days of care would not undo that.

Family Is Not Always the Answer

Why have long-term care insurance? To make sure you have enough money for the best care right until the end without depleting all of your assets. Whether your final days are at home, in an assisted-living facility, or in a nursing home is secondary. If you can pay for the most appropriate care, that decision will be based on your health and comfort, not your wallet. Many advocates of long-term care insurance actually call it “avoid nursing home insurance” because it helps pay for in-home care.