Dale Chihuly – Legendary Master of Glass

May 1, 2013 at 12:00 p.m.

In honor of his seventieth birthday in 2011, Tacoma held quite the birthday bash for their favorite native son, Dale Chihuly.

The celebration included a lecture by the iconic artist, a reception and exhibition at the Tacoma Art Museum (TAM), and a book of exquisite photographs, Dale Chihuly: A Celebration, that describes how Chihuly’s love of the natural beauty and art of the Pacific Northwest became major influences on his work.

TAM director Stephanie Stebich writes in the forward, “When you come to Tacoma, you know immediately that you have arrived in Dale Chihuly’s hometown. Evidence of his generosity and love for the city are everywhere—from the historic Union Station, a former train depot now filled with major eye-catching installations, to the spectacular Chihuly Bridge of Glass that serves as a welcome to downtown for pedestrians and motorists alike.” She tells of his gifts of major pieces to the TAM in honor of the artist’s mother, father, and brother. And she notes other installations and support Chihuly has given to organizations around the city.

“Without his vibrant art and expansive vision, Tacoma would be a very different place.”

Chihuly’s generosity, vision, and influence are without question. Because of Chihuly, the Pacific Northwest has become a Mecca for glass artists and glass lovers from around the world. What’s more, this bold, prolific, innovative, one-of-a-kind artist and entrepreneur has forever changed the nature of glass itself, transforming it from a decorative art and functional craft to a fine art reaching monumental scale.

Chihuly’s artworks can be seen in the permanent collections at more than two hundred museums around the world, and can also be found at concert halls, universities, garden conservatories, luxury resorts and other widespread settings and locations. In 1994, President Bill Clinton presented Chihuly’s work to Queen Elizabeth and French president François Mitterrand.

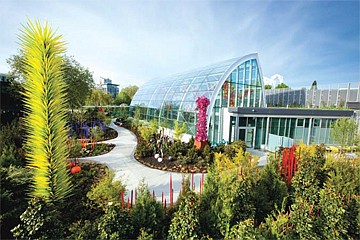

The Northwest is blessed with myriad opportunities to see Chihuly’s work including the new kid on the block, Chihuly Garden and Glass, located at the foot of the Space Needle. The exhibition opened one year ago, in May of 2012. At the dedication ceremony, Chihuly said, “It is every artist’s dream to be able to showcase their work in one place and I am pleased to have this opportunity in my home community. The best works of my career are brought together in this exhibition and I hope everyone likes it.” Chihuly Garden and Glass features an Exhibition Hall and the centerpiece Glasshouse – a dramatic structure housing a suspended 1,340-piece, 100-foot-long glass sculpture. The Garden provides a backdrop for sculptures and other installations.

The Beginnings

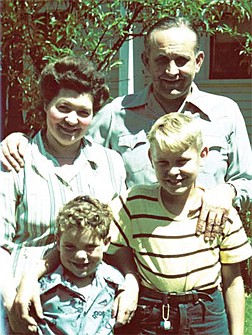

Dale Patrick Chihuly was born in Tacoma on September 20, 1941.

“My father came out of the coal mines and became a meat cutter, then a union organizer,” he writes in Chihuly: 365 Days, a richly-photographed book showcasing forty years of his work. It is peppered throughout with personal observations by the artist. “My mother was a housewife…and I was close to my brother, who was six years older than me.” Tragically, his brother was killed in a Navy Air Force training accident when Dale was only fifteen. “The next year my father died of a heart attack when he was fifty-two, and that left my mother and me with no money, in debt, and my mother never having worked for all the twenty-five or thirty years that she’d been married. And so my mom went to work as a barmaid, more or less, at a tavern nearby the house.”

Dale began work at a young age mowing lawns and washing cars; he worked as a paper boy, in a supermarket and as a janitor. “…and when my father died, they put me in the union, the Meat Cutter’s Union. I was only sixteen. I don’t think I was supposed to be in the union until I was eighteen, but because my father was a union organizer, I was a cardcarrying member of the union. So, I worked nights and went waterskiing every day.”

By his own admission, he was not a good student. “The only reason I went to college was my mother really wanted me to go.”

His mother Viola was a major influence in his life and Chihuly remained very close to her until she died in 2006 at age 98. Timothy Anglin Burgard, curator of the Fine Arts Museums in San Francisco, describes how Chihuly’s “fascination with color can be traced to vivid childhood memories of his mother’s abundant flower gardens and the spectacular sunsets he and his brother viewed with her. As Viola Chihuly later recalled… ‘I’d be right in the middle of peeling potatoes or something, and I knew just when the sun was about to set because I could see it from our kitchen window. I’d clap my hands, which meant, Come on, we’re going to run up the hill. And we’d tear up to the top, one on each side, me holding on to their little hands as they flew up there.’ ” (from Dale Chihuly: A Celebration, Abrams Books).

At his mother’s urging, Chihuly attended the College of Puget Sound, (now University of Puget Sound) and took a weaving course that first year. Then he transferred to the University of Washington to study interior design and architecture, motivated, according to Chihuly.com, by a term paper he did on van Gogh along with the experience of remodeling his mother’s rec room. In 1962 he interrupted his studies to travel to Europe and then to Israel. “I remember arriving at the Kibbutz as a boy of twenty-one, but leaving as a man in just a few short months. Before Lehav, my life was more about having fun, and after Lehav I wanted to make some sort of contribution to society – I discovered there was more to life than having a good time…After the Kibbutz experience, my life would never be the same.” He became a model student, and his life as a prolific workaholic had begun.

Forays into Glass

Chihuly first learned to melt and fuse glass at the UW in 1961. When he returned to college from Israel, he began experimenting with incorporating glass shards into woven tapestries. “I started by fusing bits of glass together and then started weaving bits of glass into tapestries.” He earned the Seattle Weavers Guild Award in 1964 for his innovative use of glass and fiber.

And then, in 1965, “One night I melted a few pounds of stained glass in one of my kilns and dipped a steel pipe from the basement into it. I blew into the pipe and a bubble of glass appeared. I had never seen glassblowing before. My fascination for it probably comes in part from discovering the process that night by accident,” writes Chihuly. “From that moment, I became obsessed with learning all I could about glass.”

He completed his degree at the UW in 1965 and went to work as a designer for a large Seattle architectural firm. He was awarded the highest honors from the American Institute of Interior Designers, but soon learned working for a big firm was not for him. “I applied for a Fulbright in weaving to go to Finland. I received the Fulbright, but was turned down by the host country because I didn’t have a place to go to study.” He later received another prestigious Fulbright Fellowship to study glassblowing in Italy. “Had I gotten the original Fulbright, I might have ended up being a weaver.”

During this period he continued working in glass and discovered that the first glass program in the country was at the University of Wisconsin. Determined to study there, Chihuly went to work for six months as a commercial fisherman in Alaska to earn money for graduate school. In 1966 he started the glassblowing program on a full scholarship.

After finishing his program, he enrolled at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and received an MFA. Excited to learn as much as possible about glassmaking, he was awarded the Fulbright fellowship that took him to Venice and the famed Venini glass factory. “At the time I came to Venice in 1968, glass artists in the United States worked by themselves.” The teamwork he observed at Venini became critical to how he works today. “I realized that if you worked with half a dozen or more people, you could achieve things you could never do alone.”

Upon his return, he established a glass program at RISD and embarked on a full-time teaching career for eleven years. During that time, "I started dreaming about a glass workshop where I might be able to work with students and colleagues in some wonderful place that was inspirational and beautiful,” writes Chihuly. “I never considered anywhere but Washington State.” He co-founded Pilchuck Glass School in 1971, located in Stanwood. It was a place to develop ideas and experiment. “Nothing held us back…” he observed. “People came from all over the world and pretty soon they started living in this area and moving to this area. Now the Puget Sound region has more glass shops than anywhere else in the world besides Venice.”

Accidents: The Icon Emerges

In 1976 on a trip to Europe, Chihuly was in a car accident that left him blind in his left eye and permanently damaged his right foot and ankle. He was hospitalized for weeks and sustained 256 stitches to his face. Although the accident took away his depth perception, he continued to blow glass until 1979 when he dislocated his shoulder in a bodysurfing accident. After that he was no longer able to hold the glassblowing pipe.

“In a way his career seems to have blossomed from then,” said Peter Blake in Chihuly at the V&A, a film directed by Peter West in 2002.

“Once I stepped back, I liked the view,” he told Regina Hackett of the Seattle PI. He could see his work from more angles and anticipate problems faster, she writes. “He explains that he’s more choreographer than dancer, more supervisor than participant, more director than actor.”

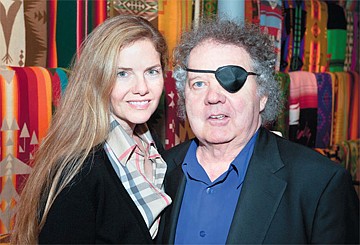

In Northwest Design & Living (Fall 1993), Jon Krakauer, who describes Chihuly as a frizzy-haired, eye-patched, swashbuckling bundle of kinetic energy, wrote of the teamwork: “Each move is tightly choreographed, and the crew performs as smoothly as a crack team of cardiac surgeons.”

Chihuly also took to drawing to communicate his ideas to the team. “So I’m able to draw and work with a lot of color and that inspires me…. I rely very heavily on [the glassblowers] to look at the drawings… sort of a symbiotic relationship that goes back and forth.” Drawing has become an important element of his work as an artist.

“Working with a team is good for me… It inspires me… I’ll conjure up some crazy idea that the team gets behind and says, ‘Well if that’s what Chihuly wants to do, that’s what we’ll do.’ The teams kept getting bigger and wilder, and the pieces became more extreme. Well, one thing led to another,” he writes of the extravagant and colossal pieces and installations that he has become known for. “I like it more on the edge. I don’t care if we lose pieces. I’m always saying ‘Push it further, make it bigger. You don’t know how far you can go until you go too far.’ The essence of his work, he has said, is collaboration and spontaneity.

Chihuly is credited with developing a number of innovative techniques and has won numerous honors and awards. “His collaborative approach revolutionized contemporary American glassmaking and is considered one of his most significant contributions to his field” (Chihuly.com).

Chihuly Today

“I rolled the dice and quit teaching in 1980…I moved back to Seattle officially in 1982. From the beginning, I wanted to find a studio on Lake Union.”

His first Lake Union studio was the Buffalo Shoe Company Building, and then he purchased Van de Kamp, near Lake Union for his hot shop. In 1990, “…I got lucky – Pocock, a famous boat builder, was selling his business and building. I was fortunate to be able to take over the building, which I call ‘The Boathouse.’ The Boathouse is also, and most importantly, my studio. Glassblowing goes on in the building seven days a week.”

Outside of work, Chihuly spends time with his family, wife Leslie and son Jackson, travels, enjoys movies and his diverse collections. “It’s very important for me to work regularly, but it’s also important to get away from the glassblowing and to travel and to draw. So it’s a combination of working and escaping.

“I exhibit widely…it gives me great pleasure that probably millions of people get to see my work. And my work gives people a lot of joy, and that makes me feel like I’m a really lucky guy.

“When I was in a pharmacy one day getting a prescription, I had a 93-year old lady come up to me and tell me how great it was to see a show of mine a couple of years ago. And I can’t tell you what a thrill it was to stand there and talk to this old lady, and to see the joy on her face and the smile when she was able to talk to me about seeing this artwork that had brought something into her life.”

Unless otherwise attributed, all quotes from Dale Chihuly are taken from “Chihuly:365 Days”