Jim Whittaker: To the Top of the World and Back Again

November 1, 2012 at 7:21 a.m.

Seattle native Jim Whittaker turned a love of nature and a thirst for adventure into a string of precedent-setting achievements.

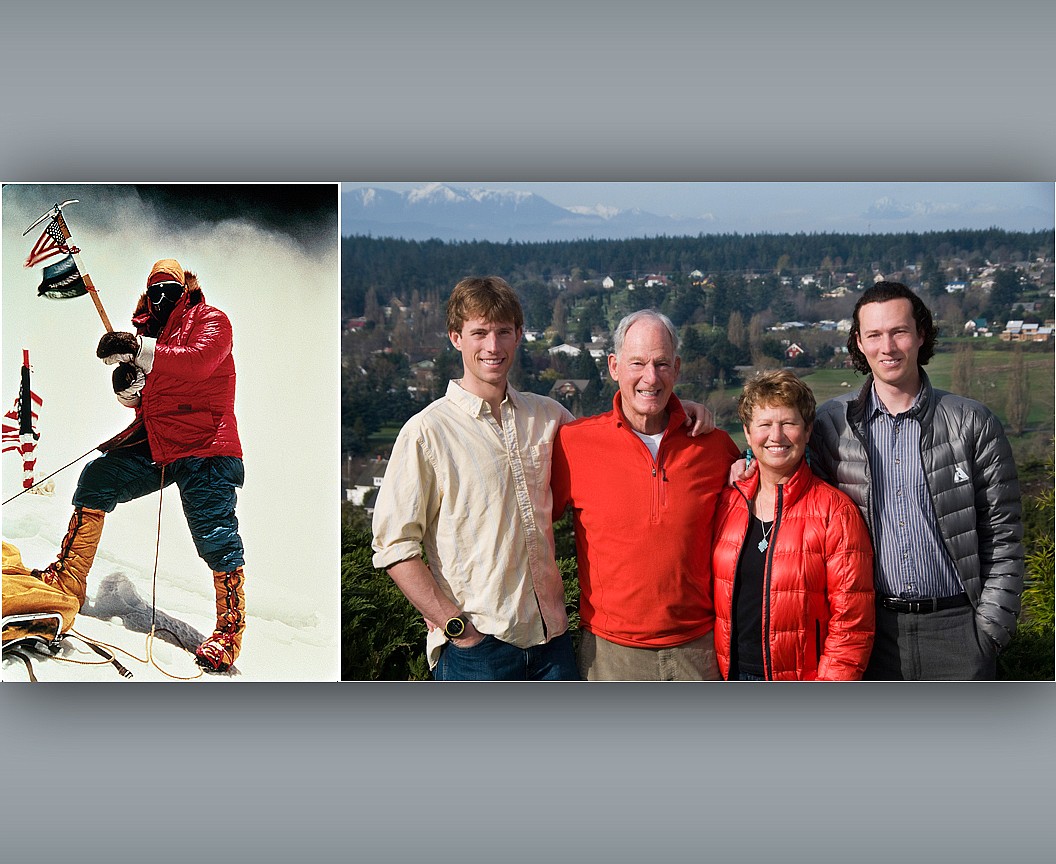

Jim Whittaker was the first American to climb to the top of Mount Everest, the world's tallest peak; the first full-time employee and eventual CEO of Recreational Equipment, Inc. (REI); and the leader of the first U.S. expedition to successfully climb K2, the world's second-highest peak. At age 60, he led an International Peace Climb that ranks as the most successful Everest expedition in history. And then he went sailing -- for four years and nearly 20,000 miles with his family.

Jim has credited his accomplishments both to the Boy Scouts, which fostered his concern for the environment and taught him to camp, hike, and climb; and to his mother, who taught him to take chances.

“As children, when we would climb up a fence or a tree she would never say ‘Be careful’ or ‘You will fall.’ She'd say ‘Have fun’ or ‘Isn't that wonderful?’ We never thought we would fail or fall” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 1998).

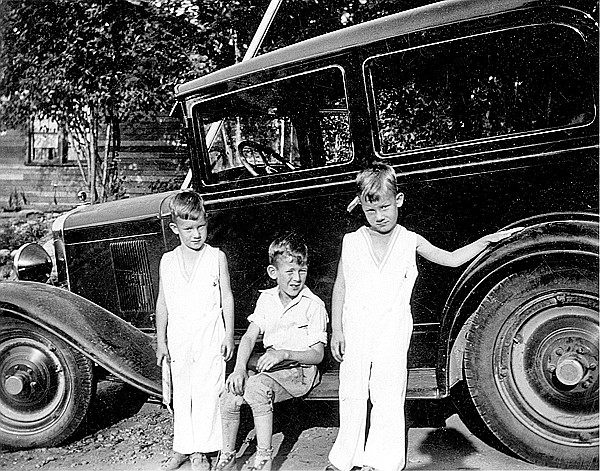

James W. “Jim” Whittaker was born on February 10, 1929, ten minutes ahead of his twin brother Lou. They grew up with their older brother Barney in the Arbor Heights neighborhood of West Seattle, the sons of Hortense Elizabeth and Charles Bernard Whittaker. Their father sold bank alarms and vault doors.

Full of energy, the twins joined Boy Scout Troop 272 when they were 12, the Explorer Scouts when they were 14, and The Mountaineers club when they were 16. They went from West Seattle High School to Seattle University, where Jim would earn a degree in biology with a minor in philosophy. But their minds were mostly on mountains.

While still in college, they scaled many peaks, belonged to the National Ski Patrol, were charter members of the Northwest Mountain Rescue and Safety Council, and served as professional guides on Mount Rainier.

The Whittaker twins graduated from Seattle University in 1952, during the Korean War, and promptly were drafted into the U.S. Army. They spent one more summer guiding on Mount Rainier, then went to Fort Lewis for basic training. They were assigned to teach skiing and mountaineering to Special Forces troops at Camp Hale, high in the Colorado Rockies. Before leaving, Jim married Blanche Patterson, a University of Washington student he met while she was working at the soda fountain at Mount Rainier’s Paradise Inn. She moved with him to Colorado. There, besides skiing and climbing for the Army, Jim began weight training and added 20 pounds of muscle to his 6-foot-5 frame.

Jim and Blanche returned to Washington in the spring of 1954, where Jim regained his guide job on Mount Rainier and resumed working at Osburn and Ulland, the Seattle sporting goods store where he worked part-time before his Army stint. Their first son, Carl, was born on October 3, 1954.

At age 25, Jim was offered a small job that grew into something big. Lloyd Anderson, a mountain-climbing friend, had founded something called The Co-op in 1939 as a way for Northwest climbers to get hard-to-find European mountaineering equipment. It had grown to 600 members with annual sales of $80,000. Anderson asked Jim to be its manager for $400 a month plus half a percent of gross sales. Jim started on July 25, 1955, working in a second-floor accountant’s office at 6th Avenue and Pike Street in downtown Seattle. For seven months he was the only fulltime employee. He stocked shelves, packed orders, and swept floors.

In 1960, the business was renamed Recreational Equipment, Inc., and began a period of phenomenal growth. When Anderson retired, on January 1, 1971, Jim became president and CEO. By the time he left eight years later, REI was a $46 million business with more than 700 employees, branches nationwide, and hundreds of thousands of members.

While REI was still operating out of a 20- by 30-foot room, the Whittaker twins already had been to the top of Mount Rainier dozens of times and to the summit of Mount McKinley, North America’s highest peak at 20,320 feet. They were ready for bigger things.

Mount Everest

They got their chance early in 1961. A mountain-climbing movie producer and director named Norman Dyhrenfurth invited them to be part of a 1963 expedition to scale Mount Everest, something no American had done. Only nine men had, starting with Edmund Hillary in 1953. Because of Jim’s connection to REI, he was picked to be the expedition’s equipment coordinator.

The team assembled in September 1962 for practice on Mount Rainier. With departure time nearing, Lou Whittaker decided he couldn’t go because he and some partners were about to open a sporting goods store in Tacoma.

Although not the most accomplished of the 20 members of the expedition, Jim was the biggest and probably the strongest. And he might have been the most determined.

“I was strong and powerful and optimistic, and I didn’t know anyone that was any stronger in mountaineering than I was,” he said. “And I figured if Hillary could do it, then what the hell, I could do it.”

The expedition headed out from Katmandu February 20. It was a massive undertaking. More than a quarter of the costs were paid by the National Geographic Society, by far the biggest backer.

There were 27 tons of food and equipment, about 900 porters, and 32 Sherpas, ethnic Tibetans who lived at about 12,000 feet in Nepal and were legendarily strong climbers. The expedition rode by truck for 15 miles, then walked the remaining 170 miles to Everest, forming what Whittaker described as “a mile-long millipede.” The hike took a month.

Two days after they established base camp at 17,800 feet, tragedy struck. Climber John E. Breitenbach of Jackson, Wyoming, was killed while picking his way through the steepest part of the glacier. He was buried under giant blocks of ice.

Stunned, the other members of the expedition pondered their loss, then resumed their quest. On April 17, they began stocking upper camps, with Jim often the one breaking the trail. His ropemate was Nawang Gombu, a 5-foot-3, 120-pound Sherpa and nephew of Tenzing Norgay, the Sherpa who had summited with Hillary. This was Gombu’s third Everest expedition, including the historic one in 1953.

Whittaker, Gombu, expedition leader Dyhrenfurth, and Sherpa Ang Dawa were the first to attempt to summit. On April 30, they staggered into the highest camp -- 27,450 feet, less than 1,600 feet from their goal, and spent the night in a terrible storm. Despite 60 mile-per-hour winds and temperatures as low as minus-30, Whittaker felt he had come too far to stop there. At about 6:15am May 1, he and Gombu left their tent and headed into a ground blizzard so ferocious that they couldn’t see their feet. Soon they were half-climbing, half-crawling.

“No one gave us much of a chance to reach the summit,” said Jim. “I didn't know what was happening below. Do you go up or down? All I knew was what I had to do. You were so committed, working for years on this, being halfway around the world. We wanted to summit so bad. You can see how people die" (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 2005).

At 1pm, they reached the top, stumbling the last 50 feet side-by-side. They were out of oxygen. Jim’s two water bottles were frozen solid, and he had frostbite in one eye, despite wearing goggles. He planted an American flag in the ice, and he and Gombu took photos of each other. “It wasn’t sublime or a moment of clarity,” said Jim. “I just suddenly thought, we’ve got to get down.”

After a scant 20 minutes on the summit, they staggered back. Dyhrenfurth later described what Whittaker had done under the circumstances as miraculous and superhuman (Ullman, p. 190). Conditions were so severe that no more attempts were made for three weeks.

Four other Americans reached Everest's summit during the same expedition. But Whittaker was the name people would remember. “Gradually it dawned on me,” he wrote in his autobiography, “that my life had changed forever.”

Home Again

On June 24, Jim arrived at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport with two of the expedition’s other climbers-- Luther G. “Lute” Jerstad, a Mount Rainier guide from Gig Harbor, and Barry Prather, an aeronautics engineer from Ellensburg. They were welcomed as heroes, riding with their families in open convertibles through downtown Seattle, with crowds lining 4th Avenue and serpentine streamers flying from office building windows. In a July 8 Rose Garden ceremony at the White House, President John F. Kennedy presented the National Geographic Society’s highest award, the Hubbard Medal, to each member of the Everest expedition.

Jim Whittaker‘s photo was on the covers of Life and National Geographic magazines. Stories about him appeared in Newsweek, the Saturday Evening Post, and elsewhere. He was recognized by The Seattle Times as the state’s top newsmaker of the year.

The National Geographic Society picked Jim to lead a 1965 expedition up Mount Kennedy, an unclimbed 13,095-foot peak in the Yukon that had been renamed in honor of the assassinated President, John F. Kennedy. After accepting the job, Whittaker learned that Senator Robert F. Kennedy would be one of the climbers. Whittaker let Kennedy be the first to summit. The mountaineer was impressed by the senator’s level of fitness and his quick, inquisitive mind. The next winter, Whittaker and his family spent Christmas with the Kennedys in Sun Valley, Idaho, the first of several vacations they would share.

When Robert Kennedy decided to run for president, Jim became his Washington state campaign manager. They spoke often, including the night of June 4, 1968, when Kennedy won the California primary election. Minutes after they talked by phone, Kennedy was mortally wounded by an assassin. Jim Whittaker flew to Los Angeles that night and joined Kennedy’s wife, Ethel, and younger brother, Edward, at the senator’s hospital bedside. Jim was holding Kennedy’s hand when he died, and was a pallbearer at his services.

Jim’s marriage had been in trouble since before he climbed Everest, partly, he wrote, because he was gone so often, working long hours during the week and climbing on weekends. The couple divorced in 1971. By then Jim was REI’s CEO and president, and they had three sons – Carl, 16; Scott, 14; and Bobby (named for Kennedy), 4.

A year later, Jim was chairing a meeting of the U.S. National Parks Advisory Board in Calgary when he met Dianne Roberts, executive assistant to the regional director of Parks Canada. She had graduated from college in three years, had hitchhiked alone around Europe, and had a passion for photography and the outdoors. They were 20 years apart in age, but like-minded in many ways. They married on June 9, 1974, on the deck of his new West Seattle home.

In 1975 Jim led an expedition up K2. At 28,250 feet, it was only about 800 feet shorter than Everest and considered more difficult to climb. Four previous U.S. efforts had failed to reach the top. Included in the expedition were his wife Dianne, who would photograph the climb for National Geographic, and his brother Lou.

It didn’t go well. The expedition was plagued by problems and after about five weeks Jim declared the expedition a failure. Determined to learn from that outing, another expedition was organized in 1978 – with Dianne but without Lou. The expedition was a history-making success.

Nearing age 50, after 25 years at REI, Jim retired in 1979. He and Dianne started a family with the birth of Charles (Joss) Roberts Whittaker in 1983. They also bought acreage on a bluff west of Port Townsend, where they moved after the birth of their second son, Leif Roberts Whittaker, early in 1985.

In 1986 Jim took a position with Magellan Navigation, a prosperous company making hand-held global positioning devices. But not yet done with mountains, Whittaker agreed to head an international expedition on Everest in 1990. The idea was to bring together mountaineers from Cold War enemies – China, the Soviet Union, and the United States – to demonstrate what could be accomplished through trust and cooperation. About the expedition Jim wrote, “We would hold the summit of all summit meetings, enemies becoming friends.” Despite overcoming conflicts, the Peace Climb ultimately was the most successful Everest expedition in history.

Before leaving the mountain, Whittaker’s three-nation group burned, buried, or packed out nearly two tons of trash accumulated from previous expeditions. Through the years he had seen evidence of nature being “loved to death” by growing numbers of hikers and climbers. “My thought was that if people get out in nature, it’s like going to church,” he said.

In 1996, Jim and Dianne sold their Port Townsend home, bought a 53-foot steel-hulled ketch named Impossible, loaded up their sons – Joss, 13, and Leif, 11 – and set sail. They traveled for four years and nearly 20,000 miles, with extended stops in Fiji and Australia, studying the cultures of the places they visited.

And then it was time for reflection. Forty years after their historic climb, Jim Whittaker, 74, and Nawang Gombu, 69, met again on Mount Everest. This time their families were with them. They hiked 40 miles to base camp, then climbed to about 18,000 feet for a toast.

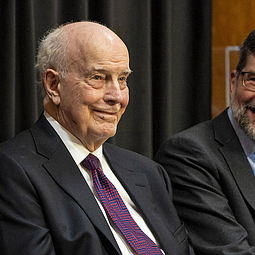

Celebrating a Still Active Life In 2009, the Whittaker twins celebrated their 80th birthday with nearly 300 friends and relatives at the Space Needle. Even after double knee replacement surgery, Jim Whittaker was still skiing last year at age 83 and plans to continue at 84. He is an active public speaker.

In addition, Jim says, “Our son Leif has now climbed Everest twice. Joss is working on a PhD in Archeology.” Last month his wife, Dianne, rowed in Boston at the Head of the Charles Regatta, the world’s largest two-day rowing event.

Jim likes to stress that life is an adventure and that nature is the best teacher. “My thrust,” he said, “is to get the people out. I tell them there should be ‘no child left inside.’ ”

He adds, “Mother always told us, when we were roughhousing, to ‘Go outside and play.’ I would urge everyone to “GO OUTSIDE AND PLAY.” Outside, in Nature, is where you learn to love it. If you love it you will take care of it and it will be there for your children and their children.”

To see more of Jim’s photos and to order an autographed, personalized copy of Jim’s award-winning memoir, A Life on the Edge: Memoirs of Everest and Beyond, go to http://www.jimwhi...">www.jimwhittaker.com.

This article was adapted from an article by Glenn Drosendahl, originally published in www.HistoryLink.org, March 16, 2010. HistoryLink.org is an evolving online encyclopedia of Washington state and local history. It is the first and largest encyclopedia of community history created expressly for the Internet

This article appeared in the November 2012 issue of Northwest Prime Time, the Puget Sound region’s monthly publication celebrating life after 50.